Mr Ibekwe’s spit is raining down on my desk as he asks for my Maths note. I see the curl of his lip and his palm flexing against the smooth, skinny cane and I know I should be worried, but my entire body is humming with curiosity. There is no space beneath my skin for fear. He’s running his thumb against the cane, like it’s a comfort, like he’s appeasing it, reassuring it that it will soon bite into soft skin. I imagine it coming down on my palm, whistling through the air to land sharp and stinging.

I do not care. I just wish I knew what they were saying. They’re talking about me. I know from the way their whispers glide up my spine, the way their eyes slither down my face and chest and knees.

It’s nice to be looked at. Not the suspicious way my classmates look at me, as if I’m going to report anything they say to a teacher. Or the bored looks teachers give me when I ask questions. Or the cursory glances my parents toss at me during the holidays to confirm that I’m still alive before their eyes glide inevitably to my brother Ime, like moths to his bright, charming flame.

They look at me like they’re curious.

Edisua and Grace are similar, but you wouldn’t know by looking at them. Edisua is tall and lean-limbed and plain-faced while Grace is the shortest girl in SS1, chubby with delicate, striking features that won her the title of Red House Princess last year even though she was a junior. It’s their eyes, I think. That’s what makes them look alike. There’s a knowledge there that makes them look older, wiser. I wish I knew what they know.

They’re best friends. They must be. I think of them as a unit, a single entity with one murmur of a voice.

Grace has been my classmate since JS1, but Edisua is new. Our class teacher Miss Benson ushered her in unceremoniously one Wednesday in the middle of Easter term, about a month ago. I knew the girl was strange from the first time I saw her with her lazy eyes and too-long neck. Who starts a new school during second term? Who steps into a new beginning on a Wednesday?Her eyes slid over our faces with mild curiosity, as if we were the ones who should be nervous. I felt her eyes on me and looked up. Looking her in the eye felt like electricity, like suffocation, like falling, a shock to all the senses. She cocked her head in mild interest and turned her gaze to Grace, where it settled. That’s when she chose her. Since then, they’ve been inseparable.

I watch them sometimes, taking leisurely walks around the field after afternoon prep, Grace listening intently to the words falling carelessly from Edisua’s mouth, their hands clasped between them as they giggle. I always wonder what they’re giggling about. I want to know what’s funny. I want to be interesting enough to make someone laugh. Maybe even Edisua.

I fish my textbook out of my schoolbag and hand it to Mr Ibekwe. He flips through the pages halfheartedly and passes to the next desk disappointed, with his cane hanging limp by his side. He stops abruptly at Edisua’s desk.

“You!”

Edisua turns her head to him slowly. Edisua never hurries. Whether she’s lifting a forkful of bland Tuesday coconut rice to her lips or skimming her pen across a page, there’s a measured quality to her gestures, as if she’s spent time considering each twitch of muscle, each jerk of her joints. As if she has all the time in the world.

By the time she turns her head to fully face Mr Ibekwe, his annoyance has risen. His temper has always been bright and hot, but what we all really hate about him is how plainly he enjoys inflicting pain.

He wags his cane at Edisua, “Where is your Maths textbook.”

“I don’t have one.”

Mr Ibekwe’s smile slices his face in two. He has thin, sharp canines which make his glee a ravenous-looking thing. Edisua looks almost amused.

“You don’t…have one.”

“No. The bookstore said…”

“Stand up!” he shouts, tapping the cane sharply on the floor. She should be pasting a remorseful look on her face, staring down at her shiny black ballet flats, anything but shrugging nonchalantly and continuing to speak. But she’s completely unbothered, and she does exactly that. I cringe as she continues.

“Mr Usman said there are no more copies of New General Maths at…”

We hear the cane before we realise what has happened, a high whistling sound like the wind whipping through the trees just before a storm. It lands with a crack on Edisua’s arm. He didn’t even bother to tell her to extend her palm.

Edisua touches the tips of her fingers to the spot on her arm where the cane landed, then slowly looks up until her eyes are locked on his. My skin prickles as they continue to stare at each other.

“Shut up! Stupid girl…did I ask you to–”

He chokes on his words.

Someone at the back giggles as he hacks out a cough. Then another. And another. The cough takes hold of his body, shaking his shoulders and snapping his neck forward. No one is laughing now.

The chords of Me Ibekwe’s throat strain against the skin of his neck as he clutches it, struggling to speak. His eyes redden and begin to water as he falls to his knees and begins to wheeze. Tobe who sits in the front row begins to scream and the class prefect, Eni runs out to get help.

Edisua says nothing. She just continues to hold his gaze until he’s lying flat on his back, with drool leaking from the side of his mouth, tears streaming sideways into his ears as he whines pitifully. Then she smiles and looks away, and Mr Ibekwe sits up suddenly, coughing and gulping mouthfuls of air.

Edisua sits back down without being instructed to, smoothing the starched white sleeve of her uniform. She sees me staring at her and smiles. I smile back before I can catch myself.

*

That night, I don’t sleep. I toss and turn, my mind calling back the image of Mr Ibekwe on the floor, helpless and clutching for breath. I feel my heart slapping at my ribs, blood rushing to the tips of my ears. I can’t get it out of my head. Mr Ibekwe with his biting insults and smooth, long cane, curled on the floor like a rumpled gala wrapper, and Edisua standing over him. I let out a long breath.

On nights like this, when I can’t sleep, I like to sneak up to the balcony on the third floor of the hostel. It’s the only balcony that faces away from the teachers’ quarters, and Matron never has the energy to climb all the way up there. Because of this, the third floor balcony is a place where things happen.

Chizoba Ejiofor once waved a red bra like a flag at Jeremiah Cobham from there. Joyce Inyang insists she saw the ghost of one of the hanger-aborted babies the SS3 girls keep telling us their seniors used to throw away like rags. Or was it the ghost of one of the hanger-wielding seniors? I try to remember as I push open the termite-eaten door. Slowly, so it doesn’t creak.

The night air is different here, like a cold palm caressing my cheek. It’s only when I’ve shut the door with a conclusive click that I realise I am not alone.

Edisua and Grace are leaning on the chipped popcorn concrete of the balcony railing. Edisua is whispering impatiently at Grace. Grace’s eyes are watery and red.

“I can’t!” Grace says.

That is when Edisua turns to me.

“What’re you doing here?” she asks, like I’m a fly she’s found nestled in the middle of her Saturday morning akara.

“The same thing as you,” I respond. I try to punctuate it with a sharp hiss, but it comes out wrong, like the buzz of a drunk mosquito. Why does this girl always make me feel like an insect?

Edisua walks toward me until her nose is an inch from mine, “Are you sure?”

I feel my head nodding, even though I didn’t instruct it to. I swallow and rub my fingers together nervously. My palms are sweating.

“Alright,” she nods, “You can stay.”

“What do you mean she can stay?” Grace whines.

“You heard me. Now do it.”

“Edisua, I can’t. I really can’t.” Grace shakes her head vigorously.

My curiosity beats my confusion and I ask “Can’t what?”

“Jump,” Edisua says simply, pointing over the balcony.

“What?” I ask. But she’s already turned her attention away from me.

“Do it…” she pauses for a second, a thick, weighted second.

“Do it now…or you’re not my best friend anymore.”

“I said I won’t!” Grace snaps, then runs back into the hostel with a click of the balcony door.

“Well,” Edisua says when she is gone. She considers my face like I’m a shirt she’s assessing for stains. She walks up to me and holds my hand tentatively. She looks so sad. I want to fix it.

“Do you want to be my best friend, Ini?”

I’ve never heard her say my name. It sounds like a discovery on her tongue. Last week during morning devotion, the chapel prefect, Esther Oghenevo spoke to us about old things passing away. When Edisua says my name I feel my sins sloughing off. Sins of silence, of fear, of unimportance. On her tongue, in her hand, I am a new creature.

Suddenly my mouth feels full of spit. I’m afraid that I’ll drool if I speak, so I just nod.

She smiles, and it’s so stunning, so brilliant—like the sun has risen at midnight.

“Good.”

She reaches into the deep pocket of her thin sky-blue nightgown and removes a packet of biscuits.

“Let’s share,” she says, handing it to me.

The pack fits neatly into my palm. The packet has no brand name, just a swirling red and black logo that makes me dizzy after a few seconds of staring at it.

I tear it open, and the biscuits inside are round and cakey. Edisua watches as I bite into one. It’s sweet and thick, sticking my teeth together as I chew. I have to struggle to swallow it. I almost spit it out, but I don’t want to insult Edisua by not enjoying her gift.

When I’m done, she smiles at me and takes one for herself. We chew in companionable silence, and she tells me about her mother’s chicken stew and a new pair of high, high silver heels her sister has just bought. I nod along smiling, swallowing spit to try and get the taste of sweet metal off my tongue.

*

They find Grace’s body the next morning. Folded neatly on the ground below the third floor balcony. She is unbroken, unbleeding and still, lips peeled back from her teeth, mouth wide in a final scream.

The matron calls the guards to clear away the body before the breakfast bell, but not before JS2 chatterbox, Ibinabo Green sees it through her room window. She is the one who describes the body and face that once belonged to Grace to us, between gasps and sobs.

“She…she…she…” the girl mutters, the first time any of us have ever seen her short of words.

Classes are cancelled that day. During night devotion, Matron says a tearful prayer for Grace’s spirit. I hear a muffled sound from Edisua. Joy Akande, the most wicked girl in SS2, walks over to her and rubs her back with a pitying look on her face.

But I know Edisua is not crying. She’s holding back a laugh.

The next morning, while I’m swirling my watery oats in my breakfast bowl, Edisua sits next to me.

“Hi,” she drawls.

“Hi,” I respond, after a pause.

My heart is slamming against my ribs. My breath is catching against the rungs of my throat. I feel every hair on my forearms stand at abrupt attention. Self-preservation is a muffled whisper in the back row of my mind, telling me I should be afraid. Mrs Bala taught us about animal instincts in Biology last term. About lust and fear and hunger. She said fear is a safety mechanism, nature’s way of warning us.

“Grace,” she says the name like it’s something rotten, something she wants to use the roof of her mouth to scrub off her tongue, “Grace was a bad friend. She didn’t trust me. Will you trust me, Ini?”

Her eyes are wide and watery as if she’s scared I will say no. As if I could.

I know then that something is broken in me, that something has overridden sense and safety and nature, because when Edisua whispers “If you trust me, meet me at the third floor balcony tonight.”, I simply nod and swallow a spoonful of oats.

*

My roommates should not be sleeping so soundly. The door to the third floor balcony should not be unlocked. It should not be so easy for me to oblige Edisua. But it is. And I’m here on the bacony. And so is she.

She takes my hand, and my lungs cease to function.

“Do you know why you’re here?”

I shake my head, afraid to speak, afraid to shatter the moment.

She frowns at me, “Yes you do.”

She pulls me to the railing and taps it with her slender index finger.

“Climb over.”

I can’t refuse. I throw a leg over so I’m straddling the railing, then cast her an uncertain glance.

She nods encouragingly, “The other one.”

“I…I’ll fall.”

“I won’t let you. Don’t you trust me?”

“I do.”

And that’s all it takes. I inhale a deep, shuddering breath. I keep my eyes on hers as I lift my other leg over the railing. I’m dangling, gripping at the pockmarked paint of the thick railing. I feel my fingernails scrape against it, but I don’t let my eyes leave hers.

She peels my thumbs off the railing, then my index finger. I gasp helplessly, but I don’t scream. She takes both of my hands and for a moment I think she’s going to pull me back over and tell me I’ve passed her test. That I’ve proven my loyalty. And then she lets go, and I drop.

But I don’t fall.

Her eyes are holding mine, and I am standing on air.

She giggles and claps as I levitate, gasping at the impossibility of it. She lunges over the railing and spins around me.

“Come,” she takes my hand, “Let’s fly.”

Crisp wind floods my nose and chest and throat as I let a wild laugh escape me. Edisua’s hand is in mine. Her eyes are on me and for tonight, we are the swirling sisters of the wind.

*

I’ve never had a best friend before. Yes, I talk to my classmates. I eat dinner with them. I lend them my pens. But no one has ever mattered as much as Edisua.

We do everything together. From the wake up bell to lights out, we’re attached at the hip. And everything is so much better with her.

We walk past a pack of sneering senior boys and they split like the Red Sea and allow us to pass. Teachers think twice before scolding me. During devotion, Matron punished everyone in SS1 for not clapping hard enough. Except me and Edisua. I am untouchable now.

One night, as we stand staring down from our spot on the balcony, Edisua passes her fingers over my scalp, trailing them between the ridges of my braids.

“Your hair is rough,” she notes.

I run a self-conscious hand over the top of my head.

“I hate how tight the hairdressers braid. And whenever I ask Vivian or Temi to do my hair, they tell me they have to finish doing their friends’ hair first so…”

Edisua smiles and places a reassuring hand on my shoulder, “Don’t worry, I’ll show you how to do your own hair.”

“You will?”

“Yes,” she nods, “Get a comb, a mirror, some hair cream…and a towel.”

When I come back with the implements, Edisua is sitting on the night-cooled tile. I join her there. She unwraps the towel and takes out the comb, mirror and cream I’ve nestled within it, handing them to me before gently spreading the towel over her thighs.

“Now, watch me.”

I don’t know why she thinks I need to be told.

I stare unblinking as Edisua grips her slender neck with both hands. And then she begins to twist.

I swallow a gasp, but I sit still. I don’t want her to think I’m a baby or a coward.

Edisua’s head begins to inch to the side, little by little, cracking and popping with every movement, until she’s rotated it completely and I’m staring at the back of her head. Her neck is corkscrewed into a misshapen mess. The way her skin twists and strains reminds me of the Saturdays when my roommates and I wash our towels, the way we wring them out, two girls to a towel, straining as we try to get out every last drop of water.

She keeps contorting her head until she’s facing me again, smiling. And then she grips it firmly, her thumbs just below her ears, and takes it off.

The beginning of a scream leaks from my mouth, but I suck it back in as quickly as it escapes. I will not disappoint Edisua with my fear.

She drops her head on the towel and wipes her palms on it. Her neck is a wet open wound, like a tender, jagged rose blooming from between her shoulders. I wish I could reach into it, feel warm flesh in the heart of my palm, have her blood seep under my nails and dry there, stay there.

“See?” Edisua’s head says from its perch on her thighs, “Now you can do your hair whenever you like.”

I nod shakily.

“Okay. Your turn.”

“What?” I feel a knot form in my throat.

Edisua picks up her head and places it neatly back on. I squint to check for gaps, for scars, but I find none. The skin of her neck is soft and smooth and seamless, like it’s always been.

“Don’t worry,” she grazes my cheek with a bloodstained thumb, “It’s easy.”

And it is. As she twists my head off my neck, I focus on her palm against my cheek, her nails digging gently into the back of my head. She lifts it gently from my shoulders and I feel the night breeze tickling at my bared flesh. She laughs at the shocked look on my head as she drops it on her lap. What little pain there is is swallowed by my awe.

The pain is a gateway to discovery, to the knowledge that a girl can come apart bloody and bleeding and raw, and then reassemble herself into an intact thing with a full-bodied laugh.

Edisua tugs at the end of my braid. “Next time, you’ll do this yourself. But tonight, I’ll help you. What style do you want?”

“All-back.”

*

The day Mr Ibekwe returns from leave, it rains.

Edisua and I are bundled in duvets, reading borrowed books and enjoying our Saturday, when a junior barges in, panting.

“Edisua, Mr Ibekwe is calling you. He says before he closes his eyes and opens them, you should be in the staff room.”

I don’t expect Edisua to care enough to hurry, but she does. The rain beats down on my newly braided hair as we run to the admin block without an umbrella. I wait outside the staff room as Edisua goes in to answer Mr Ibekwe.

After waiting ten, fifteen, twenty minutes outside the door, I start to worry. Not for Edisua, for Mr Ibekwe.

When Edisua comes out of the staff room, the shoulders of her shirt and the tips of her hair are still wet with rain, and her smile is almost sad.

“What did he say?” I ask as we walk back to the hostel. It’s only drizzling now.

“He said I was never going to pass his class and that he’s going to make my life miserable.” Edisua giggled, “And he called me a little witch.”

I’m silent for a moment.

“Are we?” I ask, “Are we really witches?”

Edisua stops walking and turns to me, “What is a witch?”

“I…I don’t know.”

Edisua frowns and shakes her head impatiently. She doesn’t speak again until we get to the hostel.

As we head upstairs, she says “We’re not going to the balcony tonight. But we’ll still meet up.”

“Where?” I ask, confused.

Instead of answering my question, she says: “Make sure you don’t eat dinner.”

*

That night, I dream of flying.

I’m twirling weightless through a bloodred sky, hand in hand with Edisua, and my chest feels so light I could float into the sun and burn into a joyous burst of ashes.

And then the dream shifts and we are in a white room, wearing white robes.

In front of us, there’s a table with all my favourite foods. I see the egg rolls I used to buy every day during break time when I was in Primary 4, my mother’s abak soup with melt-in-your mouth fresh catfish, the Sizzlers shawarma my father would buy to apologise after calling me useless, the roadside zobo Mrs Bassey bought us after we won the spelling bee in JS2 and in the middle of the table, a heaping plate of peppered chicken thighs perched with translucent rings of onion and chunks of tomato, like the ones Edisua got a cleaner to smuggle into the hostel to cheer me up after tmy parents missed visiting day.

My mouth waters as I stare.

“Is this for us?”

“Yes,” Edisua smiles.

I reach eagerly for a piece of the chicken, but Edisua grips my wrist.

“Before you eat,” she says, “Let me ask you something.”

I nod, waiting for her question.

Edisua’s face straightens abruptly, with no trace of the smile that was just there. In a flat, thick voice, she asks:

“Are you a witch?”

Red light stains the white walls of the room, and the smell of blood floods my nose.

I look down at the table and scream. The plates are filled with meat. Raw, red, bloody meat. No, not meat. A body in pieces. Shy pink lungs. A gleaming liver. Two plump eyeballs. A large , muscled, twitching thigh, jugs of thick, syrupy blood, and at the center, a still-beating heart nestled in a butterflied ribcage.

At the back of my mind, behind the fear and panic, is a stray thought that this is almost beautiful. Did she do this herself, I wonder. Lay this all out so prettily for me?

“What is this?” I finally manage to ask.

“It’s Mr Ibekwe.”

“Oh.”

“I asked you what a witch is earlier, and you couldn’t answer. Well I’ll tell you. A witch is a girl who is free to fly at night, a girl who can take herself to pieces and remake herself whole, a girl who takes revenge in flesh and blood. I’m a witch, Ini. Are you?”

I consider the table carefully. I pick up the pumping heart. It’s warm in my hands. I dig my teeth into it and blood bursts on my tongue. It’s sweet. I didn’t know blood could be sweet.

I look up from the heart in my hands, at Edisua’s face. She looks so proud of me.

“What else do witches do?”

Edisua smiles and takes my hand, “Whatever they want.”

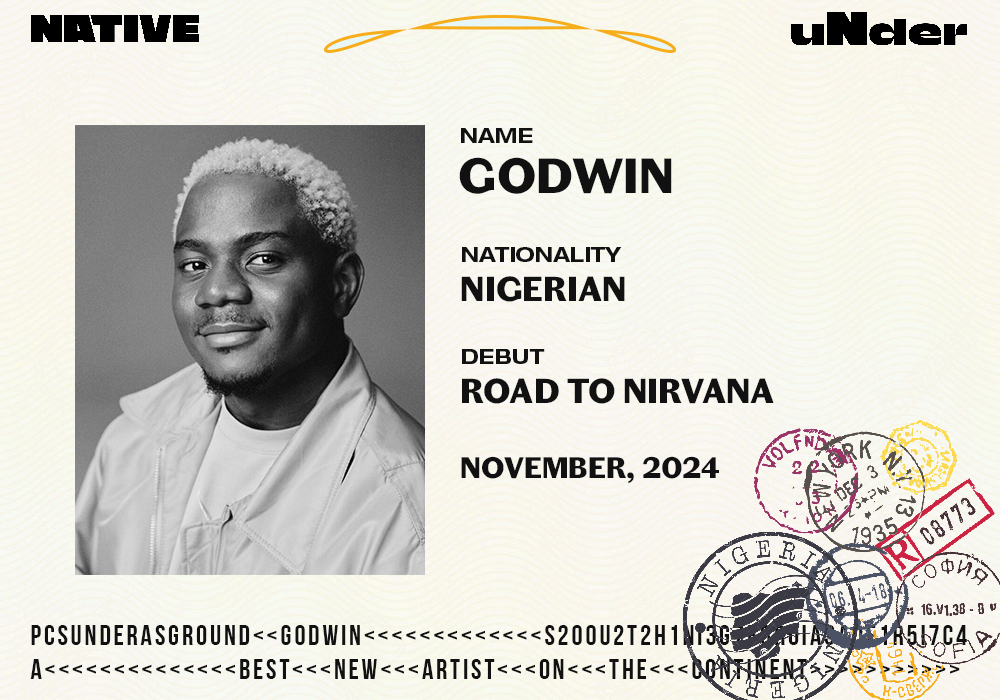

Asherkine’s rise from a grassroots content creator to one of Nigeria’s most beloved figures in entertainment is a tale of vision, hustle, and an unmistakable knack for turning ordinary moments into captivating, unforgettable experiences. Originally finding his footing behind the camera, Asherkine first gained widespread attention when he directed the visuals for Asake’s breakout anthem, “Omo Ope.” But while “Omo Ope” thrust him into the spotlight, Asherkine quickly evolved beyond the role of a director, transforming himself into a one-man powerhouse of generosity and social impact.

Asherkine’s rise from a grassroots content creator to one of Nigeria’s most beloved figures in entertainment is a tale of vision, hustle, and an unmistakable knack for turning ordinary moments into captivating, unforgettable experiences. Originally finding his footing behind the camera, Asherkine first gained widespread attention when he directed the visuals for Asake’s breakout anthem, “Omo Ope.” But while “Omo Ope” thrust him into the spotlight, Asherkine quickly evolved beyond the role of a director, transforming himself into a one-man powerhouse of generosity and social impact.

Elsie Ahachi, also known as “Elsie not Elise,” is a dedicated music enthusiast who’s turned her love for music and storytelling into a full-time passion. Starting out in 2022 with TikTok videos diving into the music she enjoyed, Elsie quickly built a following of people who resonate with her eye for talent and knack for finding artists who deserve more shine. Now, through her engaging

Elsie Ahachi, also known as “Elsie not Elise,” is a dedicated music enthusiast who’s turned her love for music and storytelling into a full-time passion. Starting out in 2022 with TikTok videos diving into the music she enjoyed, Elsie quickly built a following of people who resonate with her eye for talent and knack for finding artists who deserve more shine. Now, through her engaging