NATIVE ROOTS: Apala/Juju timeline

The sound that insists on conservatism

The sound that insists on conservatism

Haruna Ishola re-releases his 1958 album ‘The Orimolusi of Ijebu Igbo’, an album released to commemorate the sudden death of the Oba. The original album failed to make commercial success, but the reissue, riding on a wave of ethnic patriotism would become a commercial success and marked the ascent of Ishola as the most famous Apala musician of the era.

The album is distinguished for Ishola’s insistence on conservatism and refusal to join the trend of incorporating Western instruments and influences into the music. Ishola’s album would mark the beginning of the split between traditional Apala music and the more contemporary juju music.

Fatai Rolling Dollar assembles the ‘Fatai Rolling Dollar and the African Rhythm Band’, officially signalling the start of the juju movement. Rolling Dollar was already a regular fixture in the industry at this point and had dabbled in high-life before pivoting to focus his craft purely on juju music.

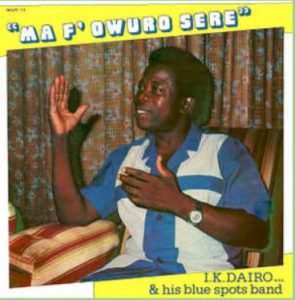

Around this time, I.K Dairo also forms the Morning Star Orchestra, after nearly a decade of bouncing between bands and working under the legendary juju artist, Daniel Ojoge. Riding on the wave of Independence driven patriotic pride and the substantiation of classical music for more vibrant Nigerian genres, both artists would pioneer the transition of juju from a niche performance art tied to local clubs and bars in Lagos and Ibadan to a mainstream music genre embraced by Yoruba communities across the country

As the country gears towards Independence, celebrations in the Western Region look for musicians who bridge the gap between contemporary sounds and a deep Yoruba heritage to perform at their events. Acts like I.K Dairo, Fatai Rolling Dollar and a young Ebenezer Obey all are introduced to the Yoruba elite and political class as they are invited to perform at celebratory concerts and events commemorating Nigeria’s new status as a sovereign nation. Many of the relationship forged during these events would sustain many of the popular juju artists at this time in the coming decade and through the war.

I.K Dairo releases Ka Soro, his second critical hit following the success of “Salome”, his first song since Morning Star was formed and renamed The Blue Spots. The song is political in a way that deviates from traditional juju music and asks for tolerance among the ethnic groups. Some suggest Ka Soro predicted the civil war that would begin in 1966 and continue till 1970.

The year is distinct because Dairo is conferred the Member of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth, in recognition of his contributions to the growth of music in Nigeria. His introductions of instruments like the accordion and Harmonica to traditional juju had elevated him as a pioneer among his peers and caught the attention of the British government. Dairo was the first Nigerian musician to be honoured in this way.

Ebenezer Obey starts The International Brothers, official marking his secession from the Bobby Bension Jam Session. He also releases “Ewa Wo Ohun Ojiri”, his official single as the leader of his new band. Obey’s exit from Bobby Benson’s troupe marks the start of the Jam Sessions eventual decline.

Obey would eventually pivot into gospel music later in his career and with him, bring a new sub-genre of juju music dedicated to incorporating traditional Yoruba praise music with Christian iconography.

Moses Olaiya, otherwise known as ‘Baba Sala’ would disband the Federal Rhythm Dandies after just a year of touring and performing together as a group to pursue a formal contract with the Western Nigerian Television (WNTV) to create a variety and comedy show with his comedy troupe, the Alawada Troupe.

Moses Olaiya’s band is best known for giving future Juju legend King Sunny Ade his musical start. Ade tutored directly under Olaiya who was a gifted multi-instrumentalist and a main figure in the Nigerian fuji and highlife scene prior to 1965, serving as the Federal Rhythm Dandies’ lead guitarist. Ade would use the momentum from his time with the band to start his own solo career.

Ishola comes to this agreement after a four-year dispute with businessman, Nurudeen Alowonole, with whom Ishola had started his first record label. Accusations of fraud and stolen copyrights had led to a strongly contested court battle and the first landmark ruling about intellectual property and copyrights for musicians in the genre.

At this time, Kasumu Adio, who would later be referred as Haruna Ishola’s closest rival for the title of King of Apala would release his first two albums ‘Iba Iya Mi’ and ‘Ina Nfe Romi Fin’, under British label Decca Records. Adio’s informal rivalry with Ishola would continue for most of their lives.

By this time, Mensah’s The Tempos had become so popular, the band routinely toured across English West Africa and Great Britain, with most of its explorations happening in Lagos. His music also created keen interest in Ghana’s Independence and would spur Nigerian agitations for Independence.

Ayinde Bakare releases ‘Live the Highlife’ as an LP issue. The album ‘Live the HighLife’ is a compendium of music the artist worked on and recorded during his critically acclaimed tour of Great Britain in 1957 with his band The Meranda Orchestra. Known across Yorubaland as Mr. Juju, Bakare had understudied under the fuji great Tunde King, and had left to form his own band in the early 1950’s. Bakare was also the first Juju musician to use an amplified guitar during his performances, and as such the first to truly deviate from traditional Yoruba music.

The reissue of Live The Highlife, was often misconstrued as a highlife album rather than a Juju album because of the success of the much younger genre.

Apala and Juju music re-converge with a financial merger between Haruna Ishola and I.K Dairo. Both at the creative and commercial peaks of their respective careers in Apala and Juju music, the duo join forces to launch STAR Records, the first African record label owned in its entirety by the indigenous artists on its bill. This merger is relevant for many reasons; it happens as the Civil War is ending and the intense hold Highlife and Afro-funk has had on Lagos’s social circuit and is an attempt by the remaining Yoruba influenced musical genres to fight the growing interest in Soul music.

Kasumu Adio would release Late Adesewa Ogunde, his tribute album to the Herbert Adesewa Ogunde, a pioneer of theatre in Nigeria, renowned for his troupe and his elaborate storytelling. Albums of this nature proved successful because they leveraged on the already outsize legend of other prominent Yoruba figures to elicit emotional responses from the audience.

Haruna Ishola releases ‘Oroki Social Club’, his first album under the management of Star Records. The album, in the tradition of Apala music honours the patrons of the Oroki Social Club in Osogbo, Ishola’s most loyal patrons. The album is an instant commercial success, selling 5 million copies and paving the way for Ishola to tour Europe and introduce an international audience to Apala.

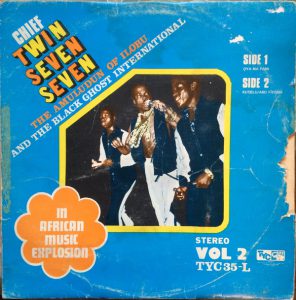

After nearly a decade working as a visual artist at the Osogbo Art School, Twins Seven-Seven moves to Lagos looking for a new challenge. As a student of the Osogbo school, Twins Seven-Seven had drawn inspiration from the works of Amos Tutuola and Daniel Fagunwa for his visual work. His background as a dancer for a travelling medicine troupe introduced him to performance art and rhythm. Both influences would be awakened by Ofo and the Black Company, an Afro funk band active in 1969 whose work was heavily influenced by their preoccupation with the mysterious ‘Ofo’ cult of Igbo land.

Emboldened by the success of this band and Nigerians returning to their ancestral religions in the wake of the Civil War, Twins Seven-Seven started a band called The Black Ghost International and released his debut album called ‘In African Music Explosion Vol.1’. The album was a critical success, carving out a new strain of Juju music and returning it to the mainstream conversation about Nigerian music.

[mc4wp_form id=”26074″]