Afropop on the rise: Kanye West’s adventures in Uganda and D’banj’s G.O.O.D music years

Coming back to Africa and other extreme fads

Coming back to Africa and other extreme fads

The Black Panther era has been a significant part of the uprise in global pop culture diversity. The themes, hits, misses and style of Marvel’s fictional African kingdom, Wakanda, claims to draw inspiration from Africa. And to the credit of filmmaker, Ryan Coogler, a Boko Haram reference in the opening sequence and a Lupita Nyong’o casting as the lead female, gave the impression Black Panther’s producers had a pulse on contemporary Africa.

Commemoratively, what the flick lacked in authentic representation taken directly from real-life modern Africa was attempted to be rectified by a Kendrick Lamar-produced soundtrack album that accompanied the movie.

Sadly, instead of curation that lives up to the pedigree of one of the most progressive rappers of his generation, Hollywood’s tone-deafness only becomes more apparent here. Kendrick, failed to do more than feature four South Africans who had no solo performances on an album featuring 23 artists in total.

Despite having the whole of Africa to source inspiration from, West Africa’s Afropop emergence was ignored and barely any attention was paid to South Africa’s House music firebrands, talkless of the urban culture revolution Gen Z millennials have spearheaded all over Africa. “But there is room to wonder what the outcome would have been if Kendrick and the rest of TDE swapped out James Blake and a few American rappers, for artists like Jamaica’s Spice, Brazil’s Karol Conká, Nigeria’s Burna Boy, Cameroon’s Jovi, or Swaziland’s Zeal & Ardor, to name a few” Noisey’s Lawrence Burney wrote, in criticism of the 14-track project.

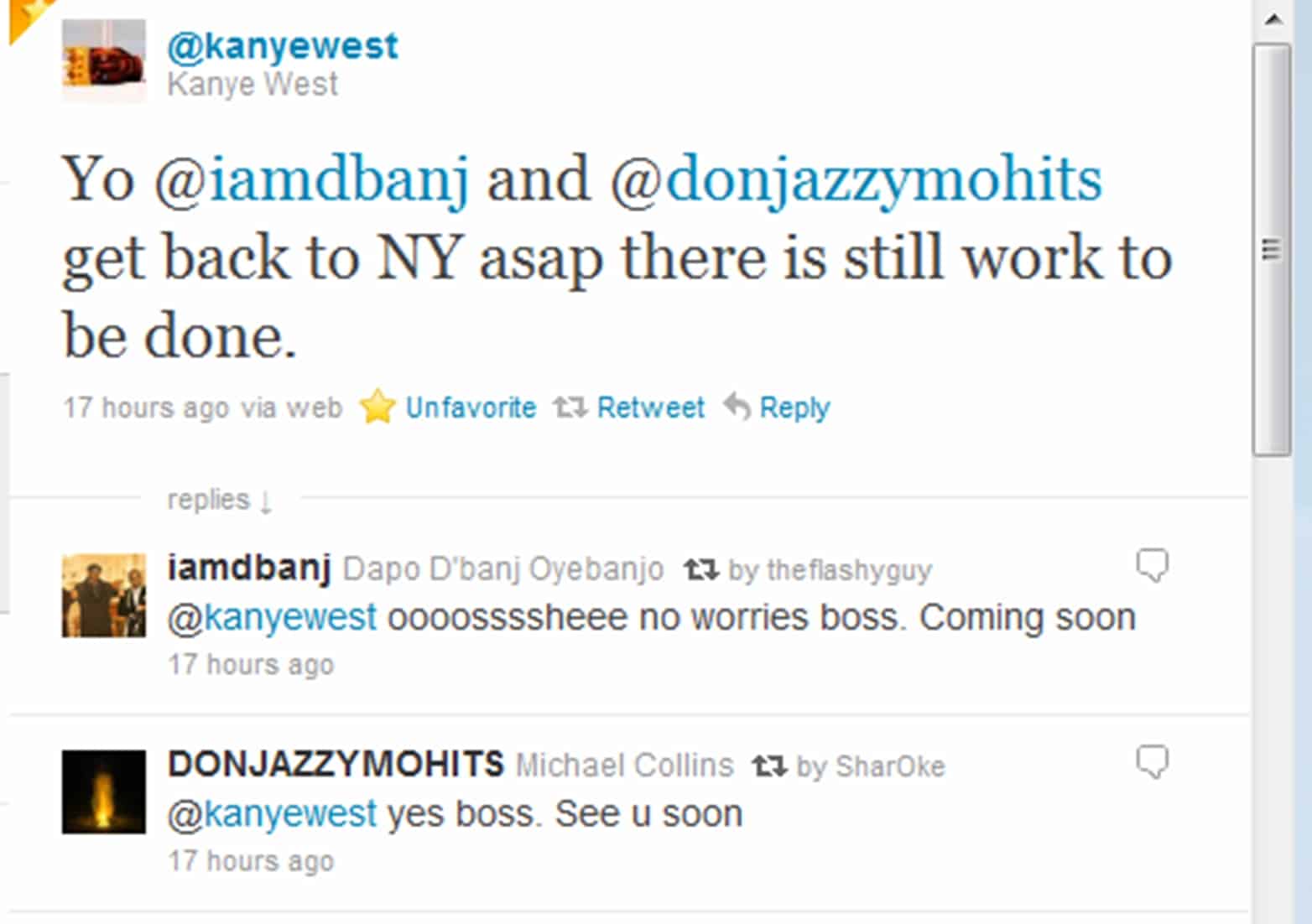

The fact sheets say that African music is finally getting the global attention it deserves thanks to the digital age, but D’banj’s G.O.O.D music deal with Kanye West circa 2011, proves this apparent build-up has been on-going for at least seven years. Even if 2face’s global recognition for “African Queen” in the mid-2000s is overlooked due to undersaturation, records still show African music crossed the Atlantic many times in last forty years through King Sunny Ade, Hugh Masekela, Angelique Kidjo, Fela amongst others.

The rise of electronic production at the dawn of the new millennium has catalysed the African music industry’s capability to record and reproduce music. Coupled with copyright laws gaining some ground, and local corporate investments in hotspots like Lagos, Accra and Johannesburg, artists all over the continent have been able to take more risks in the last decade.

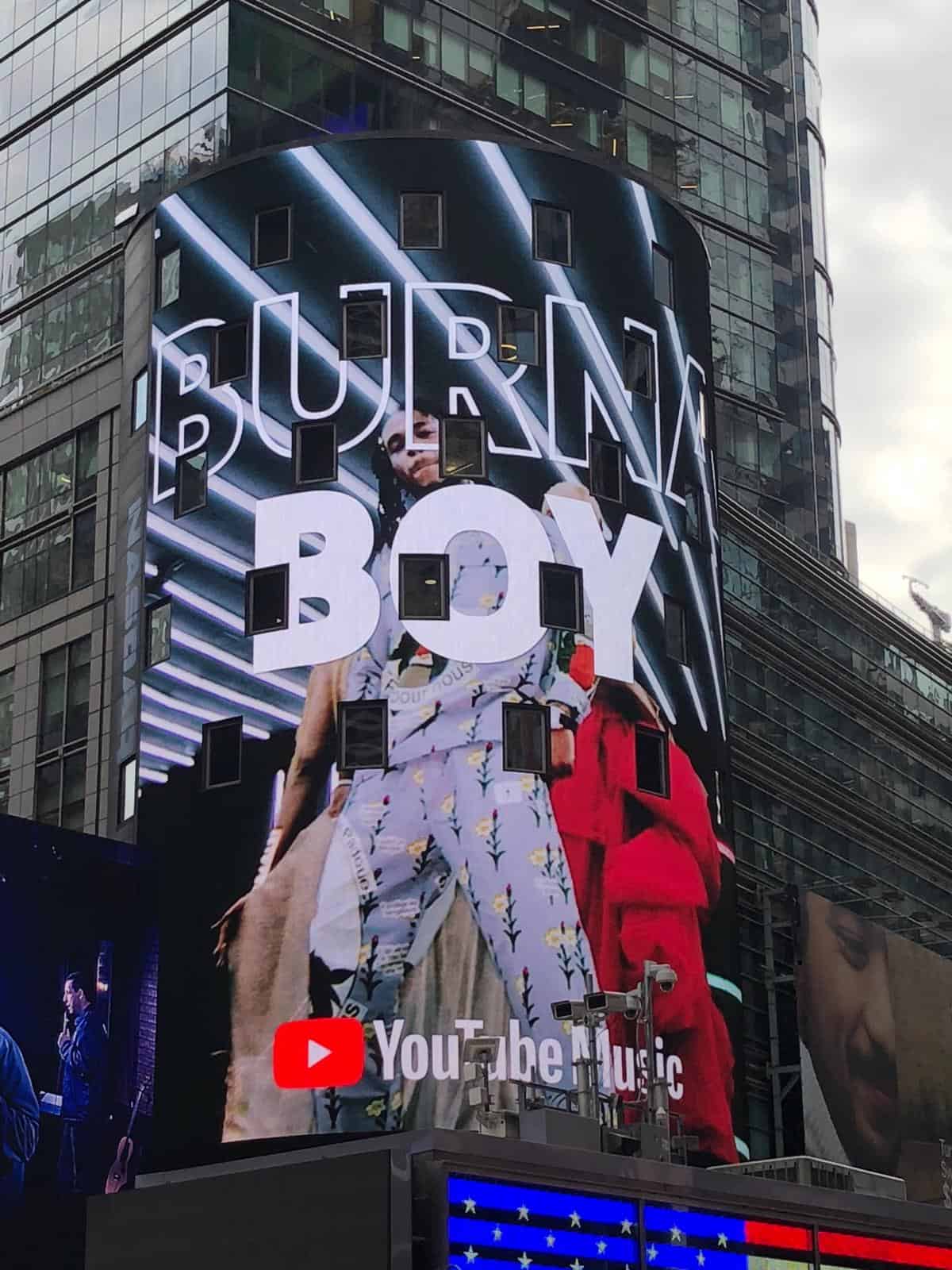

In doing this, some of the continent’s more established acts have been able to successfully double down on presentation and value. Just yesterday afternoon, Burna Boy’s face was projected across screens in Times Square, New York, where he was being celebrated by YouTube for it’s ‘Artist on the Rise’ campaign. Safe to say that in 2018, the success of an artist in Lagos, is a marker of an elite class artistry that can thrive anywhere else in the world. So why aren’t Afropop songs charting on the Billboard every other week?

The answer to that question is two-pronged. The first is every African leader’s worst rhetoric to hear, but the truth is Africa is young. Not young in the sense that people haven’t been African before colonisers came and told us we were Africans, but in the lack of a shared history that connects us as a people.

To say Africans are the same because we share a black skin would be abhorrent because we were (till date) a multitude of nations who lived sovereignly, so it didn’t help matters when colonialists came to administratively faction the continent into blocs. The result today is told in how global media struggles with finding the right approach to covering Africa. What we get instead are scenarios like the infamous Afrobeat vs Afrobeats conversation where diversity and variation in cultures often leads to misrepresentation and stereotyping.

How does this affect African music? Well, for starters, Africans have only been eligible for global recognition like The GRAMMYs as ‘World Music’ artists (with the exception of King Sunny Ade, who was nominated for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording for his 1983 album ‘Synchro System’).

There have been criticisms for the infamy of the ‘World Music’category over the years, but music streaming platforms like Apple Music still tag some African albums “World Music” till today. The term “World Music” especially fails in literal labelling, because it doesn’t encompass the full scope of the contemporary African sound, its influences or adjacent culture. This is closely related to the second reason, the rest of the world is still warming up to African music.

Music all over the world is a product of its influences and the society it is created within. For example, before Fela’s became an Afrobeat legend, he performed with a jazz band called Koola Lobitos in the 60s. After a trip to Ghana, Fela replaced his trumpet for a saxophone, combining his Western jazz nuances with Ghanian highlife’s polyharmonic scale—a style of music that was typically enjoyed by white colonialists in those years. The music got more complex as Fela mastered more instruments on the arrangement and activism was just the icing on the cake; the conceptualised sound already worked theoretically and sonically.

This same trend can be traced in how hip-hop transmogrified from the Bronx, New York to street-hop freestyles in Ikeja, Lagos. Or how South African house music is a distinct style of electronic music, even though the genre has been long viewed as a uniquely Eurocentric phenomenon. If there is indeed to be an umbrella name for Africa’s diverse sounds, it should be Afropop; as in popular music/sounds from all over Africa, whether it’s South African Kwaito music on House instrumentals or Nigerian Fuji-pop on a bouncy trap beat.

This is why Kanye West’s recent trip to Uganda to “record music” is almost nostalgic. In 2011, after a deal was brokered with his G.O.O.D music, D’banj re-released “Oliver Twist” under Ye’s imprint. He also featured on the label’s group project, Cruel Summer in the next year. Not a lot more came positively from that Kanye and D’banj collaboration, but the reason is not as sinister as fans may think.

Genealogically, “Oliver Twist”, the viral hit that caught Kanye’s attention, came at the tail end of an electronic music era for the Billboard Top 40. At the peak of fatigue for artists like David Guetta, who rose to popularity in the late 2000s and early 2010s, attention spread to rest of the world; Kanye himself freestyled a verse on Belgian singer, Stromae’s highly successful smash hit, “Alors on danse”. D’banj’s “Oliver Twist” may be an Afropop classic, but its success was also part of an electronic bubble, that burst when—dubstep-fused electronic rap-ish—songs like PSY’s “Gangnam Style” became soaring global hits.

African music is good, but it doesn’t exist in a vacuum independent from the world it belongs to. D’banj’s “Oliver Twist” did not only benefit from a timely global trend it also proved the supposed gap between contemporary African music and music elsewhere is imagined.

African music no longer needs big co-signs. Otherwise, there is a risk of the culture getting caught-up in fad thanks to people like Kanye West, who told TMZ, “we are going to what is known as Africa”, and added that the sound of forest and trees would be recorded into the music. (You almost wonder if African trees melodically whoosh differently from those in America)

As more D’banjs, Burna Boys and others whose pulse on the global soundscape can spotlight the scene in Nigeria. Perhaps, in future, Kanye West and other trend-hoppers like him, would have no choice to but to say: “we are going to where the music is hot right now”.

Fairly enough, Kanye did say, he was tapping to the spirits “flowing” through him to record the best music on the planet. And after watching both videos of Yeezus energetically bopping to Wizkid and Burna Boy respectively, It’s pretty obvious why he’d say that.

Photo Credits: FunmiOgunja.com, GuardianUK, Twitter.

[mc4wp_form id=”26074″]

Toye is the Team lead at Native Nigeria. Tweet at him @ToyeSokunbi