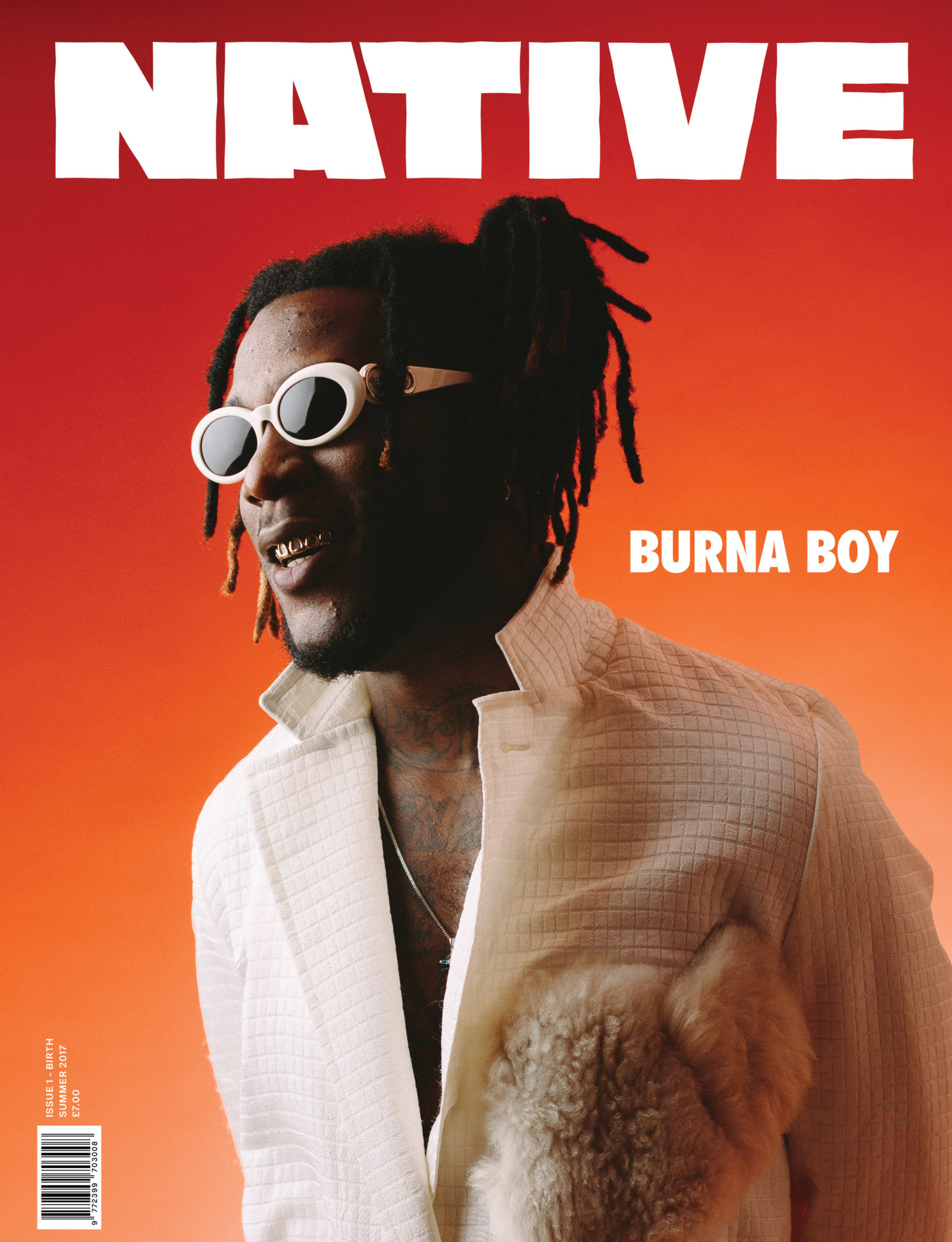

BURNA REBORN

Burna Boy's NATIVE cover story is a rare glimpse into the life of the country's most mercurial talent.

Burna Boy's NATIVE cover story is a rare glimpse into the life of the country's most mercurial talent.

Words: Ayoade Bamgboye

Photography: Chris Okoigun

Styling: Ronami Ogulu

LAGOS – “I feel like I’ve been Burna Boy since before I was born”, he exhaled rather matter-of-factly halfway through our conversation, “I’ve always been this guy”.

The house itself was unsuspecting. I don’t know why I had envisaged something strange but beautiful, a unique structure that young children could point at and say “that’s Burna’s House”, in some sort of Disney neighbourhood-hero type of way. But even that wouldn’t make much sense – despite his seemingly permanent relocation to Lagos (and currently, Lekki), Burna is, rather aptly put by the man himself at his debut show in 2011, “a Bad Boy from Port Harcourt”. In an adopted city, he has surrounded himself with family, and friends that have become family, but he still carries the aura of a mythologised outsider operating in his own world.

One of Burna’s bredrins (he refers to all of his inner circle as his bredrins), Shalala, was nice enough to escort me upstairs. We came to a small living room once we got in, and there was a child staring intently at me, eating a slice of pawpaw. Burna later told me that this phenomenal painting of the child was done by his sister, as were most of the others around the house. After walking up three floors, each one a variation of a large television, sofas and artwork, we finally came to a room. I’d call it a bedsit, but having a bedsit in the middle of a mansion is a bit of a paradox. It was technically a “bedroom”, the giant bed giving that much away. But it was populated with what felt like a hundred people, in addition to a living room and a fully stocked bar, so it didn’t really feel like one. I still had to ask Burna if this indeed was where he spends his nights. Sensing I was confused by the sheer volume of bodies, he laughed before retorting that “everywhere is everywhere.” By the end of my stay with him, I had become used to these effortlessly cryptic remarks which made no sense at all, but at the same time, all the sense in the world.

Since his relocation to Lagos in the early 2010’s, and the subsequent release of his needle-moving debut album L.I.F.E (Leaving an Impact For Eternity), Burna has long been painted by various parts of the press as an enfant terrible of sorts. From controversial Felabration outfits to imaginative rumours of the reason behind his prolonged absence from the UK, the traditional media in the country seem to be preoccupied with everything in Burna’s life other than the actual music. He admits he’s not blameless in this situation though, sometimes adding fuel to the fire by sparking back at the incessant press-operated rumour mill surrounding the music industry. “If I ever react to something in the industry, it’s because my fans keep going on about it,” he explains, “I just feel the need to appease them. Without them there’s nothing really, so I might as well.”

Is there anything you’ve done or said that you regret?

Anything that I’ve done or said that I haven’t meant, I apologise then and there for it. It doesn’t take me long to process stuff, everything I do, there’s a reason for it, but sometimes the way I pass a message, it’s just rah, mine’s landed like a slap.

His responses to questions about the industry (and thus his peers within the industry) are measured but blunt. He wouldn’t be drawn on how he felt about fellow artists jumping into the studio with anyone and everyone in the States. What in the past may have come across as marginally slighted by the perceived lack of critical acclaim, his tone and body language is decidedly different. Burna knows he is meant to be here. He doesn’t need you or me to rave about his album to remind him of his talent. Despite humorous jabs such as him stating “they know who to go to for stuff like that” when asked about being involved in political campaigns, he has successfully found a way to operate and exist outside of a mundane music industry muzzled by sponsorship millions, whilst still dictating the direction of the mainstream sound.

If nothing else, Burna Boy knows who Burna Boy is, and what he’s meant to be doing. Asked to describe himself with only 3 words, he said, “Real, great and…” he paused briefly. “I know what I want to say for the last one, but I don’t know it in English,” he pondered, before swiftly saying it in Yoruba “E li to mo na”. I stare at his blankly, wondering whether or not I should confess that I know very little Yoruba, if any at all. He was silent, so I imagined he assumed I knew what he said, at which point I had to ask, “what does that mean?”, to which he calmly replied after some more thought, “One who knows his own road.” How fitting, I thought to myself, as Burna stated this with the calm of someone who truly knows himself.

How would you describe your process of creating?

I’m not a rapper, or a singer, I’m not even an Afrobeats singer, I’m an Afro-Fusionist, it’s a spiritual genre of music, it just comes. You get chosen and it just works out for you.

No plan, no process? Isn’t that scary, aren’t you ever worried that it just won’t come?

Nope. If it wasn’t gonna come, then I wouldn’t even be here in the first place.

This sort of answer becomes somewhat of a regular occurrence during my stay with Burna: he completely believes that he was chosen to be here, doing what he is doing, and the explanation for his success is really that simple. His unwillingness to identify as an Afrobeats artist is particularly intriguing, given the legacy of the genre and his family ties to the legendary Fela Kuti; but it’s understandable that he wouldn’t want to box himself into a genre that means so much more than a certain tempo.

Pop music in Africa is slowly becoming one of the continent’s biggest exports. Watching the growth of the respective House and Hip Hop scenes in South Africa has been nothing short of inspiring, but the resurgence of African Pop music in West Africa has been breathtaking. In a world where everyone is more connected to one another than ever before, Nigerian music has travelled faster and further than many could have imagined. These days it is not uncommon to hear a Wizkid or Davido song at the club in New York. It is no longer a surprise to hear a Mr. Eazi sleeper hit on UK radio stations. When your favourite Instagram model posts a video dancing to a Burna Boy song, it’s not that unexpected.

But this sudden obsession with sounds from the motherland is not without explanation. Nigeria has long been seen as the home of the “Afrobeat”, birthed by the legendary Fela Kuti. Arguments about the exact definition of Afrobeats, what it is and what it is not, are even more heated than those seen in the UK regarding the definition of Grime. In the mid-noughties, mainstream artists started to slowly shift away from traditional Afrobeats, allowing their music to be influenced by Hip-Hop, Rap, R&B and other more contemporary sounds. Like every truly great genre, Afrobeats evolved to have its own sub-genres, appealing to different legions of fans. This seismic shift birthed the superstars of the 2010s: D’Banj, Tiwa Savage, P-Square and many more.

As the musical landscape in Hip-Hop and R&B shifted overseas, modern Afrobeats followed suit, in true pop music fashion. Burna Boy has always been seen as one of the pioneers of this shift, incorporating Dancehall and Hip-Hop on his earliest recordings, such as the encapsulating “Freedom Freestyle” off the Burn Notice mixtape in 2011, where he allegedly addresses his first stint in the UK. Artists like Odunsi [The Engine] and Mr Eazi have been quoted as classifying themselves under the genre “Afro-Fusion”, a fitting term to describe the sound of modern pop music in Africa: Afrobeats with a mix of pretty much everything else. Many other acts have since gone on to identify their music with this definition, but Burna Boy very much sees himself as the only frontier of Afro-Fusion. It’s more than a genre to him, it’s spiritual.

How do you feel Afro-Fusion is evolving? What can we expect from where it is now, and where it will be?

I am Afro-Fusion, so you’re talking about where I am and where I’m going to be, you get me? I’m just going along with it. It’s fusion because it’s everything. Whatever the spirit decides, that’s what it’s going to be.

How would you describe the spirit, is it like a feeling, or a vibe?

I don’t know! That’s like asking me to explain what the air is like, sometimes it’s cloudy, sometimes it’s beautiful, sometimes there’s smoke in it, it’s just what it is. You get me?

Your music is quite political, in that there are clear connections with current sociopolitical issues – do you feel like music should be politicised?

No, I don’t only make music like that. I make music about stupid stuff too. It’s a spiritual thing so it’s whatever I’m feeling that day. It’s just a mixture of feelings and vibes.

Do you feel a dilution in the culture of our music with the rise of international collaborations?

I’ve done a million of them, you’re going to hear too many next year, it’s not a secret, there are features with Grammy winners and all that. I’ve never actually approached people before, I think that’s what happens when you’re original and real, you get me? There’s going to be an attraction when your style is clear.

Burna sauntered around in nothing more than boxers and a warm smile, “Welcome to My Dojo” he laughed, as smoke filled the room. After I politely declined the “holy grail” on this occasion, I was offered a snack from his bedside drawer, which was literally filled to the brim with all kinds of sweet treats. I opted for a miniature Twix bar, he had a hot dog and a can of Coke, incidentally not from his bedside drawer.

It’s intriguing, the way he alternates between brother, son, partner and artist, never fully stepping out of each role, being all of them at the same time. He says as much himself when I ask him how he separates Burna Boy from Damini Ogulu. “My mum calls me Burna Boy, it’s the same thing. It’s like I’ve been Burna Boy since before I was Burna Boy, I’ve always been this guy. There wasn’t a time where I was like, yeah, I’m going to be this guy now.” He says incessantly. “There was no development, that’s just the way I was born. If you look at baby pictures, I look the same. It’s mad. When I was little I looked like this, like I had one haircut till I was 23, the same haircut, you know the Burna Boy haircut? I always had that. Then I got tired of it and grew dreads.” His impassioned answer reminded me of Gloria Carter’s monologue on The Black Album opener “December 4th”, where she says she knew Jay Z was going to be “special” because she didn’t go through any pain during his birth. The notion that those closest to icons-to-be somehow always knew they would go on to be great isn’t new, but with Burna Boy, it seems perfectly believable.

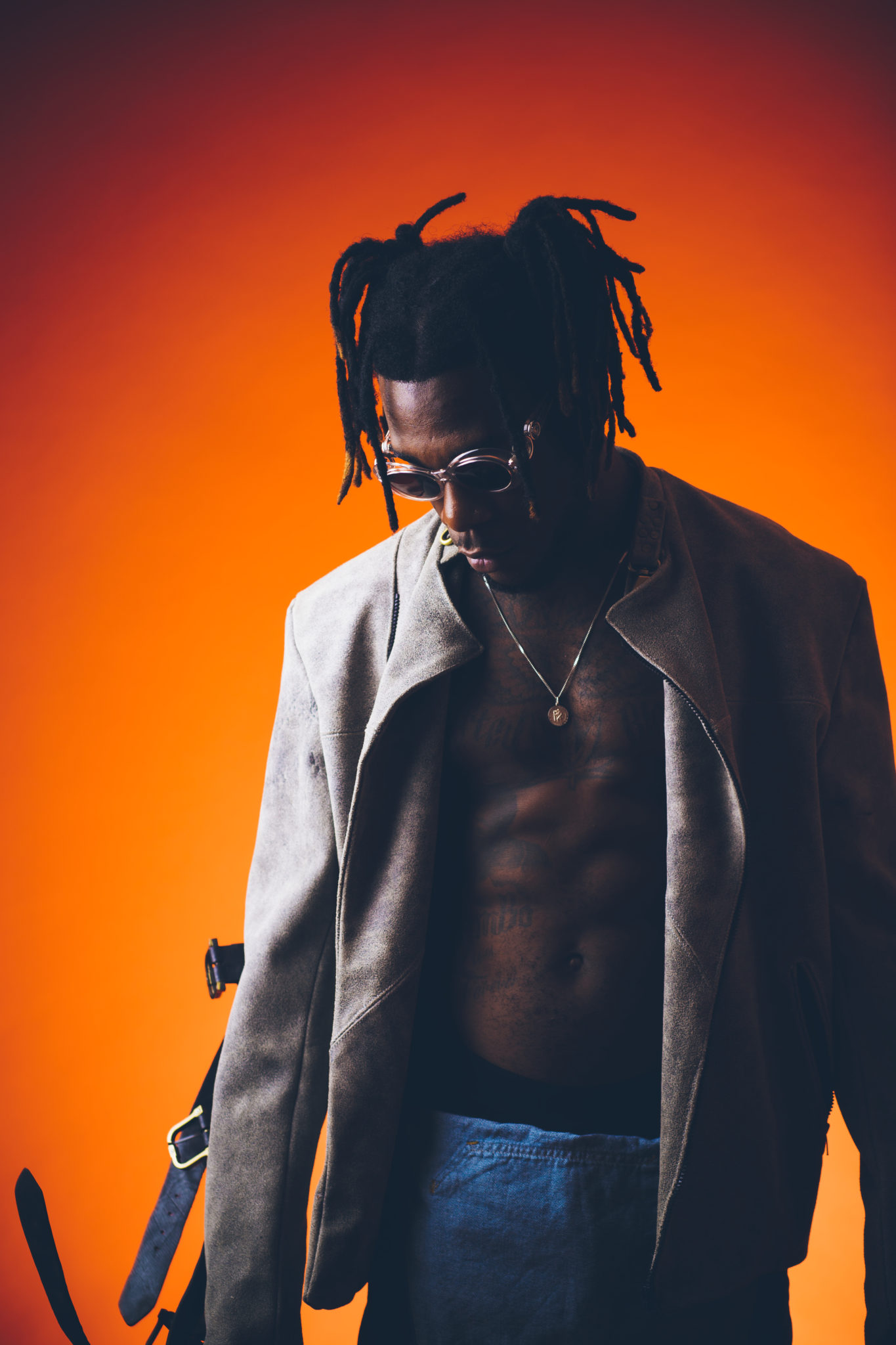

A couple of weeks later at the inaugural NATIVELAND Festival, Burna was deep in conversation backstage as J Hus ripped through hits like “Friendly” and “Dem Boy Paigon” for an adoring crowd. Flanked by his tenacious momager Mrs. Bose Ogulu, and his sister Ruonami who doubles up as his stylist, they were looking through some of the early edits of the photographs from his NATIVE Cover Shoot. “This one is sick, please send it to me!” he tells Chris Okoigun, as he stares intently at an epic shot of himself draped in a white robe, holding his trademark trap-phone, with smoke escaping from his mouth. Mrs. Ogulu agrees, “Yes please send them all to us,” she states before turning to directly to Chris, “but obviously we can’t use that one in the magazine,” she asserts firmly, with a wry smile on her face as she looks back to her son. He laughs, as if he already knew what was coming, and accepted her decision but insisted he still wanted the photo for his own personal collection.

This short exchange between son and mother, artist and manager, performer and booking agent, is pivotal to understanding the success of Burna Boy. He trusts her to protect him and his interests, taking care of the smallest problems and the biggest problems, so he can do what he does best: make music and perform it. In turn she trusts him to do just that, in a way that only he knows how. This isn’t to say that they do not disagree on certain issues, or argue like any parent and child do, but the fundamental trust is always there.

Mrs. Ogulu herself grew up in music, ironically the daughter of one of the most notorious music critics in the highlife era, Benson Idonije. He also famously managed Fela, leading to a young Bose Ogulu touring with Fela and his band, so she’s not really a typical mother-manager. She was born into music, just as her son was. As mercurial and impulsive as Bose’s Son is, it is her job to find a way to organise the madness. Managerial masterstrokes such as Burna consistently performing all over the continent, particularly in South Africa, where she has strategically aligned him with the biggest acts out there, may go unnoticed. Burna Boy doing shows in far-flung cities all over Nigeria that his mainstream counterparts conveniently omit from their tours is not by coincidence. “All the shows are equally crazy,” he says when I ask about the sold out stadium gig he recently did in Makurdi. After a similarly sold-out Homecoming show at the Hammersmith Apollo, he embarked on an unrelenting UK club tour for over a month, playing in multiple cities. These strategic moves engineered by Mrs. Ogulu is what has gained her the trust of her pride and joy, and it is what lets him be the free spirit his fans love.

* * *

From my sunken position on the sofa in Burna’s room I looked around, and was reminded that we weren’t alone. I asked Burna who was who, half expecting him to dish out some sort Arya Stark-inspired response like “The bredrins have no name”. But he pointed out Dante, AK, Montana and Shalala, each of them smiled warmly.

Are they all your best friends?

They’re my brothers, I don’t have friends, I have brothers. You think it’s a manner of speaking when I say they’re not my friends, they’re my brothers, but it’s real. Do you think if someone put a gun to your head they’d jump in front of the bullet? With me, if you can’t do that you won’t be around me. I’d jump in front of a bullet for them. You should always think about that, because at the end of the day, the people around you are important, they can make or break you

Do you make music with any of them?

[Laughing] None of them make music, these are real niggas you’re talking about, you have to understand that, these are not “popping champagne in the club” niggas.

Just like his relationships with his actual family, Rankin’ (as his fans affectionately call him) believes that mutual trust and loyalty are fundamental to being in his inner circle. He’s unbothered by material possessions and award shows. More so than anything, he wants the people around him to be more than comfortable. Every artist needs a support system when they’re creating – it’s what gives them the unerring freedom to do nothing more than make art – and Burna appreciates this, and always wants to give back to the people who give him the foundation to make music for a living. Whether it’s taking care of his more-than-blood brothers, or making sure his sister gets styling gigs for all his shoots, Burna sees to it at that the proverbial 15% is given to “people he fucks with”, to quote his latest collaborator Drake.

What do you feel like is a logical next step in terms of the progression of your musical career?

I don’t know (insistently) I just take life as it comes, at the end of the day there’s no point planning stuff because it’s never going to turn out how you planned, if it does, then it means that’s how it was meant to be. I just feel like, life is just easy like that. It’s not that complex.

What has worked so far?

The music. And being me.

What hasn’t worked?

The music, and being me.

On “My Life”, the opening track of his debut album , Burna repeatedly croons “This is just the way I am/this was not my plan”, and watching him in his element, this seems more and more like case. Burna is really just out here being himself, and sometimes it goes right and sometimes it goes wrong. Some may say his refusal to separate Burna Boy from Damini Ogulu is affecting his career, but that may be just what sets Oluwaburna apart from his contemporaries. In the music industry in Nigeria, artists go through such extreme lengths to separate their musical identities from their true identity in some faux-WWE manner, caricaturing to the point of parody. That has led some listeners to question how authentic either character is, if at all. Burna is simply incapable of this: music is his life, and always has been. It’s his gift and his curse. His fans love his genuine honesty, his peers seemingly don’t. As pop music is once again becoming one of Africa’s biggest exports, it’s refreshing to see one of the leaders of the revolution so impassioned by it.

I ask Burna about new music, expecting verbal descriptions of what’s to come, but Burna offers to play me what he’s been working on. Well, he didn’t really offer. He asked me, then just started playing it. I wasn’t complaining though. As he shuffled from one expectedly-amazing collaboration to another not-so-expected, but equally amazing duet, I couldn’t help but watch him just as intently as I was listening to the music. Despite playing the music “for me”, he didn’t once ask what I thought or even grant me a cursory glance, echoing his own earlier statement that he knows his road. This wasn’t some early critics’ listening session: he genuinely just wanted to listen to his music and I happened to be with him at the time.

As he switched tracks to a collaboration with a Grammy winner that must have been constructed in Reggae Heaven, my attention turned away from the self-proclaimed Rockstar and to the people he calls his brothers. These are the people who he spends most of his time with when he’s not performing. They play FIFA for hours, fire up the BBQ on the weekends, and do pretty much what any mid 20s group of guys do in their free time. But something struck me as odd during the song: they were rapping every bar, crooning every trademark Burna melody, as if they were listening to the track for the first time. Each one of Shalala, AK and Montana were performing the song like it was theirs, finishing off bars, going back and forth like they would in a cypher, letting the music move them, just as Burna lets the music move him. This excitement would have been appropriate if this was the first time they had heard the song, but it clearly wasn’t, judging by the near perfect recall of the lyrics. Burna and his partner seemed unmoved by his bedroom becoming something in-between a raucous club night and an emotional deliverance service: I guess this wasn’t the first time.

As I drove away from Burna’s House questioning whether I had bredrins who would take a bullet for me, I felt I had witnessed something larger than me, something way more than just a smoke session and a preview of unreleased songs. Burna’s brothers weren’t brainwashed yes-men trying to score points. They weren’t fanboys lucky to be around their favourite artist and freaking out. They weren’t even childhood friends just trying to support their mate who makes music. Shalala, AK and Montana were believers.

What’s a Messiah without Believers?