Gay is African

Queerness is African

Queerness is African

A quote in “Same-sex Life among a Few Negro Tribes of Angola”

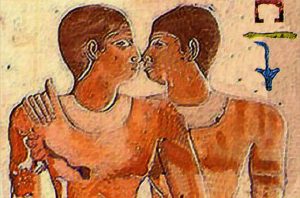

There is nothing African about homophobia. Despite what’s been constantly peddled to us by the likes of political conservatives and religious leaders, a glance at African history reveals that homosexuality is not “un-African”; rather, it is the laws that criminalize it that are. Like other societies in the world, whilst widespread African communities generally placed an importance on heterosexual marriages as the basis for family life, African societies were also characterised by a diversity of sexual expressions. Several African cultures believed that gender was not dependent on sexual anatomy. This is displayed with androgynous deities like Esu Elegba, the Yoruba goddess of the crossroads or Mawu Lisa, the Dahomey goddess.

The myth that homosexuality was absent or introduced by the “West” in pre-colonial African societies is one of the oldest and most enduring. For Europeans, black Africans, of all the ‘native’ peoples of the world, were classed as the most “primitive man”. Hence, as a primitive man, he was ruled by instinct, his sexual energies had to be devoted to his most “natural” purposes, sexual reproduction. Today, with the failure of many African governments, countries like Nigeria need a distraction that plays into the psychopolitics of the nation. Therefore, they use the virility of a true “African man” and his masculinity as a distraction, stating that it must be maintained, as gender equality and homosexuality are threats to heteropatriarchal African societies.

To understand African homosexuality, we must abandon Western beliefs and values of sexuality, love and marriage. Sexuality in pre-colonial Africa was complex: the organising of gender, sexuality and reproduction are not comparable to the rigid structures of western contemporary societies. Love, intimacy and companionship whilst welcomed, were not necessary or expected in African societies. In order to prevent depicting a forged unified mythical African homosexuality, multiple patterns of same-sex sexuality are discussed. It is pertinent to note before we begin, that in every region, female same-sex patterns were poorly documented and frequently misunderstood. These relationships were not often revealed to men, especially outsiders, hence it has seldom been mentioned by anthropologists working on the continent. However, Audre Lorde was surely correct in her stance when she stated that with so many African men working away from home, it was not unusual for African women to turn to each other.

Leading the colonization of Africa, the Portuguese became the first Europeans to discover that African sexuality and gender diverged vastly from their own. In the early 17th century, efforts to conquer the Ndongo Kingdom of the Mbundu were thwarted by King Nzinga. She had become King by succeeding her brother, which was not uncommon in the matrilineal society of the Mbundu. In the late 1640s, the Dutch military observed that Nzinga was not known as Queen, but King of her people. She ruled dressed as a man, surrounded by young men dressed as women who were her wives. This Nzinga behavior was not personal eccentricity but was based on the recognition that gender was situational and symbolic as well as personal and an innate characteristic of the individual.

Describing Zande Culture, Evans Pritchard stated, “Homosexuality is indigenous. Zande do not regard it as at all improper, indeed as very sensible for a man to sleep with boys when women are not available”. He went on further to state that this was regular practice at court, and some princes even preferred boys to women when both were available. These relationships were institutionalised, men that had sexual relations with another’s boy wife, would pay compensation. People asked for the hand of a boy, just as they asked for the hand of a maiden. The men would treat the parents of the boy acting as if he had married their daughter, addressing them as father-in-law and mother-in-law. However, when the boy grew up, he would then take his own boy wife in his turn, whilst the husband would take a new boy wife. It was not uncommon for a member of these tribes to have up to 3 boy wives in succession.

Although substantially converted to Islam by the late 15th century, the Hausas today still participate in a possession religion called the Bori cult, which many believe to have survived colonialism. Gaudio believes that there has been little if any non-African influences on Hausa same-sex patterns. In 1994 when a local Muslim newspaper characterized homosexual marriages as a western practice alien to the Hausa culture, many refuted this stating that it was indigenous to them, even though marginal. Hausa “gay” men refer to their homosexual desires as real and intrinsic, but also regarding their reproductive obligations as even more real and more important than their homosexual affairs, which are often referred to as wasa – play. Arranged, or mandatory marriage does not require heterosexual desire, neither is this desire referred to as natural or even necessary. Pre-colonial kinship obligations and family interventions ensured marriage happened. These societies did not need to suppress homosexuality, as long as it did not threaten the directive to marry and reproduce.

There were also often many African explanations for homosexuality. Among the Fanti of Ghana, where gender mixing roles for males and females were common and observed, it was explained that those with heavy souls, whether male or female, will desire women, whilst those with light souls will desire men. In the Dagara of southern Burkina Faso, it was explained that gender had little to do with anatomy. The earth is described as a delicate machine with vibrational points which people must be guardians of in order for tribes to keep their continuity with the gods. Individuals linked with this world and other worlds, experience higher vibrational consciousness, far different from a normal person, they explained is what makes a person gay. It is important to note that the Dagara were a tribe described to know astrology like no other tribe encountered and that the great astrologers of Dagara were often gay.

All over the world, people view homosexuality as a vice of other people. The recurrent British claim that Norman conquerors introduced homosexuality to the British Isles. The French view homosexuality as Italian, Bulgarian or North African, Bulgarians as coming from the Albanians, and so the story goes. African societies did not lack homosexual patterns, there is more than enough substantial evidence showing that same-sex patterns were traditional and indigenous. African same-sex pattern was not only widespread throughout the continent but was diverse. In fact, it is stated to be more diverse than those found in other parts of the world.

The situation in Europe however, was largely different. In 1533 King Henry VIII signed the Buggery Act, which criminalised sex between two men, into British law. The accepting attitudes in Africa quickly changed as penal codes were implemented against homosexual practices which were seen as felonious crimes by the British. These penal codes were based on Christian doctrines which interpreted homosexuality as ‘savagery’ and ‘sodomy’. The British sought to instill in Africans, the belief that homosexuality was a primitive practice that needed to be wiped out if we were to conform to European civilisation. Thus, the views of Europeans towards homosexual practices in Africa were rooted in White Supremacist thinking that placed African practices as primitive. The quest to eliminate the acceptance of homosexuality in Africa by the colonisers also illustrated the ‘desire to remove it from the perversions which occurred in European societies’, as Boris Bertold puts it. For example, Captain Sir Richard Burton, who was a European traveler described some parts of Africa, Asia and the Americas as a ‘sodatic zone’; describing places where European homosexuals could freely express their relationships as they could not in their home countries.

Between 1897 and 1902, the Penal Code, which had been previously enacted in India by the British, was applied in African colonies, criminalising homosexuality. It stated-:

This code created a legal basis for homophobia and is responsible for the discrimination that homosexuals face in ex-colonies today. The effect of British colonial rule over the Hijra people in India also reveals the impact of the importation of homophobia into British colonies. The Hijra people are non-binary, trans and intersex and were given legal recognition as a third gender for over 4000 years as shown by ancient records. After the implementation of the Penal Code criminalising homosexuality, the protection that this community enjoyed was removed whilst the homosexual community was also being persecuted. Although these laws were repealed after India gained its independence, this community still faces severe discrimination especially in access to healthcare.

Over a century after stripping away African culture and forcing us to conform to Western norms like homophobia, the tables have turned and the U.K now uses the very homophobia they instilled in our communities as a means of further repression. For instance, David Cameron, ex-Prime Minister of the U.K threatened to cease financial aid to Uganda as they continue to violate human rights by persecuting homosexuals.

Instances like these should be a pointer to African leaders to think for themselves rather than attempting to fit into the archaic mold of morality which was imposed on us. It becomes clearer as time goes by that morality is a social construct. Whilst the threat of withdrawing aid in the instance above appears to be intended to promote more progressive attitudes in Africa, this approach is, in the words of the Ugandan Presidential Adviser Yoweri Museveni, an ex-colonial mentality of saying ‘you do this, or I withdraw my aid’. Therefore, it is possible that the resistance against the decriminalisation of homosexuality is partly explained by the fear of neo-colonialism which illustrates that the scars of colonialism still lie deep within us. However, rather than continue in this pointless direction of opposing progressive thinking because of who it may come from, Africans need to reclaim the progressive aspects of their culture that were stripped away and evolve, as this is the route to true independence.

Nigeria has continued to maintain colonial attitudes towards the LGBT community. Homophobia in the country is now supported by the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill (SSMPA), which was passed in 2014. This heavily polices the LGBT community and imposes harsh punishments with sentences ranging from 10 to 14 years in prison.

This law sent the message to the local and international community that the Nigerian government had no intention of giving into the pressure of protecting the rights of sexual minorities. More importantly, it has further exacerbated violence against the LGBT community and has empowered the police to arrest and detain people based on their perceived sexual orientation. There are repeated reports of arrests of the LGBT community, raids of events and safe places, and even a police unit declaring it was ‘on the hunt’ for homosexuals. The homophobia displayed not only by the police, but encouraged by civilians as well, is a major reason why the intersectionality of sexual orientation and police brutality was so crucial during the #EndSars movement. Undeniably, the most disheartening aspect of the SSMPA, apart from the law itself, is the fact that it was viewed so positively by Nigerians. This again highlights the hostile environment in which the LGBT community must exist and shows the extent to which the passing of the SSMPA made an already bad situation worse.

As the SSMPA has effectively legitimised violence and erasure of the LGBT community, it is important to highlight the efforts of the community to be seen and heard.

#THEENDSARS PROTEST

The #ENDSARS protests, which first began in Nigeria, in 2016, against the SARS unit which is known for its brutality against the very citizens they were created to protect. The protests were reignited again in October 2020, provided many queer Nigerians to voice their violent experiences with the police in Nigeria. Queer Nigerians were amongst the first to join the protests. Whilst they were met with hostility by other protestors, who felt it was neither the time nor place for them to air their views, they stood strong and demanded to be heard. If anything, it amplified their voices and showed the world what a homophobic country Nigeria is. The video of LGBT activist, Matthew Blaise, an openly gay person in Lagos, screaming ‘Queer lives matter’ on the streets of Lagos garnered over 3 million views on Twitter. It was bold moves like this that made the #ENDSARS movement a notable movement in Nigerian queer history.

View this post on Instagram

Living Loud and Proud

Despite the criminalisation of the queer community, there are still people who refused to be silenced and live a life that is not theirs. They resist the law by existing. Considering the ignorance and hate that thrives in Nigeria, to say that living in one’s truth in such an environment is brave, would be an understatement. People like Matthew Blaise, Amara the Lesbian, Bobrisky, James Brown and more, have shown that they will not be silenced or policed by unjust laws. They have shown that despite belonging to a marginalised group, there is still incredible power in resistance.

However, it is worth recognising that not everyone who belongs to the queer community is privileged enough to do this. Some people face more immediate danger and risk. Therefore, it is important that we all stand in solidarity to promote queer rights and push against the homophobic laws in this country. Of course, we still have a very long way to go, considering that a lot of the homophobia we see is rooted in religious beliefs. Yet, hopefully, one day homophobic Nigerians will show even an ounce of the queer community’s own bravery, and begin to question their intolerance and hate and grow beyond that. We hope that many of the young LGBTQ+ Africans reading this know that they are seen, and are a part of a beautiful African history.

Featured image credits/NATIVE