Credits:

Words: Toye Sokunbi

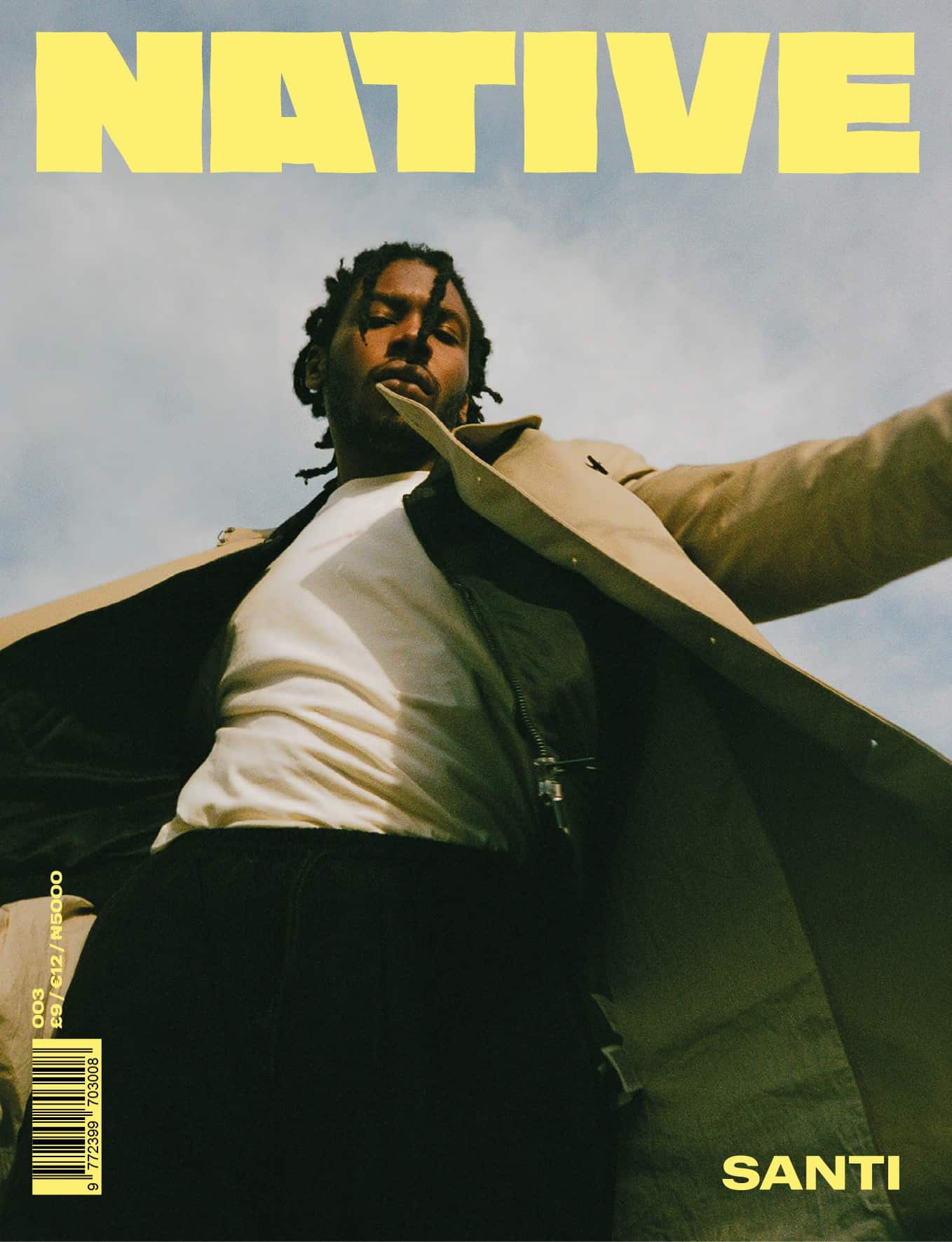

Photography: Wathek Allal

![]()

HOW ONE OF AFRICA’S MOST INNOVATIVE CONTEMPORARY MUSICIANS REINVENTED HIS WAY TO BECOMING A FORCE IN THE STRONGEST CULTURAL REBELLION IN RECENT YEARS.

There were no shawls for the Birth of Santi, nor were there any roses at Suzie’s Funeral.

These are the names of the two defining projects in the musical journey of Santi. The former brought an unceremonious end to Osayaba Ize-Iyamu’s Diaries Of A Loner mixtape series, along with his meta-persona as OzzyB – once seen by many of the earlier users of the Nigerian inter-webs as the saviour of Rap. The latter, a purge; from a hell-scape of vices which he describes were holding him back from reaching the place the “journey” was taking him.

“On Diaries of a Loner, I was on an unclear road using a very rough map to navigate”, Santi says as we start to discuss his roots in Hip-Hop, “Now I can see the whole map. It’s just left to decide where to go.”

Purposeful clarity makes things easier these days, but he is also keen to add, not much has changed. He still envisions himself as a growing artist, spends a chunk of his time by himself and wholesomely trusts in the divine timing of all things.

During our conversation, time, as a concept, is one of the first elemental indicators of Santi’s hyperrealistic artistic view. He doesn’t necessarily dismiss his days as a rapper as a formative phase in his artistry, but he also makes literal allusions to his early musical influences. “People will be surprised [to hear that] ‘okay yeah, he used to be a rapper-rapper before.’ But for me, It’s like, that’s just the side I showed you first. I mean, a 18-year-old guy, in 2010, Lagos, what other kind of music was I going to make?”

—

WHERE’S OZZY?

5 years before Santi started to cobble up his first Diaries of Loner mixtape with his then go-to-producer BankyOnDBeatz, MTV Base kicked off operations in Lagos. Prior to this, Channel O had thrived as the premier music-dedicated cable broadcast in Africa for many years, bringing all the sounds of the continent to one channel, for premium after-school viewing. The arrival of the Viacom-owned music giant transformed the landscape of the music industry we know today. Starting with 2Face’s “African Queen”, the first music video MTV Base aired in ‘05, progressive improvements in the quality and texture of Afro-Pop happened rapidly over the next decade.

Off-air, Nigeria’s growing MTV-Generation was being moulded by the spread of cable TV, mobile technology and digital sharing. Santi remembers laying on his bed, staring at the ceiling while listening to the Ja Rule, DMX and 2Pac CDs his dad bought him, off the staticky computer speakers in his room: “I used to daydream to the stories they were rapping.”

By the time he was gearing up to release his first tape in 2011, the major hip-hop records influencing his sound included an odd but well-fitting pairing of M.I’s genre-defying classic Talk About It, and Drake’s similarly veiled genre-mashing, So Far Gone.

“The day Talk About It dropped, I copped multiple CDs on the way to school and handed them out to my classmates, like ‘bump this shit’”. As a child who had grown up spending a lot of time in his own head, Santi tells me Drake’s emotive imagery and the ambient soundboards on the mixtape stuck with him the most because it fuelled his imaginative mind.

If there is anything Diaries of A Loner is a testament to, it’s how Santi draws his influences from his surroundings in real time, evolving almost instantaneously. The name “OzzyB” itself, was inspired by British collective, So Solid Crew, whose members also had cartoonish pseudonyms. That alongside his past life as a high school freestyler brought the first iteration of Santi as a rapper named Ozzy B to life.

After the first mixtape dropped, Santi began to feel uneasy with the limitations of verse structure and rhyme scheme that came with rapping in the early 2010s. Two things were happening in his life at this time: He fell deeply for someone, and also discovered Vampire Weekend and Santigold, two more of his major far-reaching influences.

“I didn’t even know what they [Vampire Weekend] were talking about, but it made me so sad every time I listened to them and thought about the girl,” Santi tells me. “Music is feeling” he believes. “Santigold had this song ‘Lights Out’, and every time I listened to it, I always felt like she was taking me on a journey, and even though I didn’t know where we were going, it didn’t matter ‘cause the drive was so mad.”

Santi appears to be very content with living with such ambiguities. While giving me a breakdown of what eventually happened to the crush that drove him to alternative music, he drifts into scenes from his childhood memories. “I was a shy weird child. At home I was very quiet, and in school, I was this wild guy. It was weird.”

It’s hard to explain what it means to be pressed for words if you haven’t grown up in a conservative country like Nigeria. In Chinua Achebe’s classic novel Things Fall Apart, after the arrival of missionaries to Umuofia, families and households started to splinter as younger family members started to break away from traditional religions. Santi’s home vs school duality mirrors that same clash between tradition and change that has always resulted from deep communication gaps between generations, due to difference in beliefs, education and societal expectations.

For any young person who had (or is having) this “normal” Nigerian childhood, the most consistent everyday struggle is safe self-expression. This is the story of the birth of Santi.

“In high school, I liked this girl in my class and I didn’t know how to tell her”, Santi began, “So I started to write stories based on the school but I’d change the name of the characters. My classmates were so into them! And they would always beg me to write new episodes. I used to do them weekly, I was just having fun really. Next thing I know, the girl figured out who she was in my stories and became friends with me”. Santi’s little high-school drama serials were probably banned by the school authorities, but we don’t talk about that. Especially after he grimly added the school shut down a few years ago.

![]()

Fast forward to Santi’s second gap year out of school in 2012, his frustrations with Hip-Hop as a primary mode of expression coincided with his eventual decision to quit school altogether. He briefly talks about his parents’ initial resistance, dramatising typical Nigerian parent anxieties, then quickly moves past it. I don’t think his “deep crush” worked out, but he also offers no more information on that subject. The light bulb moment to start experimenting, however, happened just as he began writing for his second project. “Something was changing in me. I feel like I had to switch up, but I also didn’t want to do it out of nowhere. I had to show everyone my process, and that’s why I made Birth of Santi.”

The Birth of Santi marked the early days of Santi’s Monster Boyz – the collective he now operates within. Even now, nearly 7 years after he began working on the project, Diaries of a Loner: Birth of Santi still listens like a very raw genre-blending masterstroke. Producer GMK who’d recently completed flight school at the time, joined Santi’s long-time collaborator, BankyOnDBeatz behind the boards. With the exception of opening track, “Waste Your Time”, produced by Retro Dee (Now known as Genio Bambino), both producers managed to craft an avant-garde alternative-Afro-Pop album, packed with an eclectic mash of contemporary sounds.

The 12-track mixtape doesn’t follow a single theme through-and-through, but it was a collection of sounds steeped heavily in the music that dominated the era. A large portion B.O.S still had a hip-hop filter but there was a clear sign Santi was veering into more musically adventurous terrains.

“Summer of ’95”, a promise for the true potential of Hip-Hop and Afro-Caribbean fusions predating Drake’s “One Dance”, segues into conventional Jollof Music like “Money In A Bundle”. Experimental rap songs like “Monster Sorrows”, a stand-out cut with layered vocals that could have easily fit into Kendrick Lamar’s good kid M.A.A.D city, leads up to closing track, “Lagos Party”, a disrespectfully-underrated cut laced with Popcaan-influenced patois.

Once the rollout was done, Santi also categorically decided his days as a rapper were over. According to him, that part of his artistry already served its purpose. “Rapping to me was being rebellious, like ‘I don’t want to do anything I don’t want to do’.” he says. “But music is a feeling. Even if you don’t understand the lyrics, there is a feeling you can get from hearing sounds that can take you to a place, or help you remember memories distinctively and I wanted to show feelings”. He returned to school once again, this time around in Dubai — where he’s lived ever since.

It had been important for Santi to show the world his transition with his previous project, but the aftermath left fans with more questions than answers, with regards to what to expect next. Birth Of Santi serves as the closest interpolation between the Santi we know now, and the Ozzy B we grew up with. Santi found himself at a crossroad – a familiar feeling throughout his artistic and human journey. Ozzy B holds a very special place in the hearts of 20-somethings who yearn for their teens. It reminds us of the days of Hulkshare and Limelinx, the days of DatPiff and NotJustOK tags all over songs, the days of thinking Nigeria had its first true Rap Messiah. Ozzy B was one of our own. So for Santi to make the decision to put him down, it felt personal – like your best friend moving away just before the summer started, despite all the plans you’d made. There’s a startling sense of entitlement fans develop with artists. We fall in love with one version of a person and their art, and demand nothing more – or less – than this exact thing. The entitlement is mirrored around the music world; from the longing for the return of “Old Kanye” to fans clamouring for The Weeknd to revisit the dark hallways of the House of Balloons, music lovers need their fix: And it better be the right dosage.

One can only imagine the pressure that accompanies the diversion from the comfort zone for both artists and their fans. It takes an artist so utterly convinced of their vision, to be able to step away from what they know, and step into the unknown – especially when the former is working so well for them.

Santi understood the gravity of the decision he was making, and did not make it lightly. He did not make any grand announcements, official statements or tie himself into a release schedule. He simply picked up what he already knew, and went into his sanctuary – the cave that is his mind. With a broadened palette for daring compositions, gained from summers trawling the fringe genres Santigold had introduced him to through her fantastic eponymous album, Santi was ready for the next phase in his metamorphosis. The artist formerly Known as Ozzy B had not quite killed his former self, but simply shed its skin, to prepare for a fresh battle.

THANK YOU SUZIE

When Santi emerged from his cave in the winter of 2015, something was different.

![]()

In the time that had passed, the African music landscape had changed drastically, for the better. Mainstream behemoths like Davido and Wizkid were becoming bonafide crossover superstars, utilising both pan-African and international collaborations in the respective missions; the bridge between the UK and Nigeria was growing stronger by the day, thanks for the likes Mr Eazi and Maleek Berry; and even the South had something to say, with Cassper Nyovest selling out his first 20,000 capacity arena, and an 18-year-old Nasty C making a claim for the vacant Hip-Hop throne.

In what turned out to be the beginnings of Suzie’s Funeral, Santi started exchanging music with a 19-year old producer-artist called Bowo – known to many now, as Odunsi The Engine. “I sent this a kid a beat sample for me with a hip-hop vibe. But when he sent it back, It didn’t work. So I told him to work on it some more, then [he] returned it with these dancehall drums and that’s how we made ‘Steal A Dime’”. There was no project on the horizon at the time, but the resulting track was their first official collaboration and Odunsi’s induction as an extended member of The Monster Boyz.

“Because of how much time I spend in my cave, the few times I come out to see what’s going on, I see that there are kids who are now finding themselves and confidently going through ‘the process’.” Santi explains of his first encounters with a fresh-faced Odunsi. “It was like looking at yourself because you know they have also had to fight self-doubt, or African parents who think choosing music is throwing your life away.” Santi disconnected from an industry he thought ill-fitting, and when he returned, he found there were kids just like him. The next chapter had begun.

***

On the 30th of June 2016, Santi introduced us to Suzie.

“Suzie’s Funeral happened at a strange time in my life,” Santi explains, with a hint of sorrow in his voice. “I was losing friends, I had too many vices and I was in a place I didn’t like”. To rid himself of these post-adolescent habits that he felt were sabotaging his growth, Santi looked inwards once again and conjured Suzie: a fictional character who became his muse for the the mixtape that changed everything.

“Suzie and I got on this journey to an unknown place”, Santi narrated. “We didn’t know where we were going, or what we were looking for but we sha knew, we would know when we saw it. As we went further and further along, the journey became more dangerous. Demons…monsters…evil people. Just as we were about to reach the destination, the obstacles became even harder to beat. Suzie decided to stay behind and fight so I could go on to reach my dreams. She sacrificed herself. Suzie’s Funeral is the tribute to all the love, vices and people I had to leave behind to become the very Santi you know today.”

Santi intentionally avoided dropping any singles before the mixtape, as he wanted his latest re-introduction to be on his terms: as a full body of work. He still raps on tracks like “The Running” and “Demon Flow”, but the most progressive standouts off the album featured a mash of Afro-Caribbean mannerisms on alternative electronic production, as seen on the standout record “Gangsta Fear”. The dichotomy between Santi’s incantation-like verses and Odunsi’s crystal clear delivery was the latest feather in their growing relationship.

“I was at home chilling one afternoon when GMK sent me the beat,” Santi tells me of how the song was made. “I went to my studio, recorded this freestyle on it and sent it back. Then Odunsi added a verse that I never heard until the day before they dropped the song and called it ‘Gangsta Fear’” The mutual trust between the brotherhood dubbed Monster Boyz is plain to see, and it is one that they continue to build on. No other track on Suzie’s Funeral captures the universe the project was set in more vividly, and this was exemplified brilliantly in the accomplishing visuals, directed by Santi himself.

In the video, Santi and Odunsi are pictured in an unspecified shanty, somewhere in Lagos. Unlike similarly executed videos since, where squalor and poverty have been used as some sort of trendy new Instagram filter, Santi and co-director, Ademola Falomo, capture the subtleties of everyday ghetto life instead. Santi is seemingly drugged-out in the opening scenes, while Odunsi is seen contemplating, leading up to the video closing at a party with the Monster Boyz.

If you hadn’t noticed how immensely self-aware Santi’s universe was before “Gangsta Fear”, the mid-video interlude before Odunsi’s verse is a great reference point. The scene cuts from Santi and Odunsi to vintage Associated Press footage of a riot on the streets of Lagos, then glitches into a reel of retro-filtered clips of nightlife and Lagos’ Ikoyi Club. Just before the music continues, a flash graphic with the lone text ‘$1 = ₦500’ flashes, then Odunsi returns to the screen singing his infamous opening lines “She wanna go shopping in Dubai. Shorty make a grown man cry…”

In a country where a chunk of the population still lives below the poverty line, a bunch of teenagers with iPhones, flaunting designer fits seems like an obvious invitation for vitriol intended for their assumedly wealthy families. No doubt, people are poor in Nigeria, but like every misrepresented cultural space, the problem here is with the dangers of a single narrative – and Santi’s visuals are rebelling against this. “Gangsta Fear” dropped in the same year that Nigeria officially went into a recession, after months of economic ‘stagflation’. The ports froze, black market rates for the dollar went as high as five hundred Naira while the cost of literally everything shot to the skies. Headlines were flooded with constant reports of hidden stashes of money being uncovered at unassuming locations. On the other side of the coin, a bustling community of creatives were finding their voices, with a newly energised Santi at the forefront of the rebellion.

To remove the context from a subject is to rob it of a history that justifies its value or existence. One of the more refreshing aspects about our conversation is how Santi doesn’t shy away like from speaking for his “Alté” contemporaries like Odunsi The Engine, Lady Donli and Tay Iwar. Instead of giving a straight-forward response when I ask if he has his kept competitive spirit from his rap days with regards to his peers, Santi gives a sharper summary of the venerating circumstance they all share in common: the freedom to create without limits.

Suzie’s Funeral was Santi at his most expressive: he had finally let us into the new world he created for himself. “I wanted kids to feel how I felt in class parties when Sean Paul came on. I wanted to tap into that feeling, in my own way.” He still thinks there are elements of the OzzyB in Santi, but the key difference was that he was finally making music in a way that felt true to who he was trying to be. “The thing with rapping is that, that was me expressing myself using the music I listened to. But the act itself didn’t feel like me. I haven’t stopped rapping, I just don’t rap in 16s anymore.”

It’s a particularly poignant and self-aware observation from Santi here, one which encompasses the new realm of consciousness he seems to have accessed. If you search hard enough on Youtube, you’ll find one of Santi’s earliest Youtube accounts, Osayaba213, adorned with a collection of freestyles and an Arsene Wenger display picture. This was a teenager in 2010 Lagos, who grew up on 9ice, M.I. and Naeto C, who idolised Lil Wayne and Drake. Why wouldn’t rapping be his first medium of self-expression? It makes complete sense, and is really quite simple when thought about, but it’s rare for for one to make such a blunt analysis of self. He’s almost looking at himself, outside of his own body, able to judge everything at face-value, with no added sentiment or even sympathy.

![]()

We barely knew Suzie – introduced to her like a toddler at the funeral of a long lost aunt – but she was without a doubt the most important figure in the life of Santi so far. Just as he built on the foundations of OzzyB to become Santi, he made another bold step in leaving behind his partner, knowing he could only complete the mission alone.

SANTI 3.0

It’s hard to tell if Santi is a talker or not, if you’re only asking polar questions. When you leave him to speak at length, pop culture references tumble out of him unabated. No matter how obscure the subject, a quick allusion to a film, song, artist or anime character, could be chipped in to make metaphors more vivid. He uses these influences when creating: whether it’s his own music or the visuals he directs for his peers – which fall somewhere in between Wes Anderson and Old Nollywood. When I ask him to summarise his career so far into three major landmarks, Santi says “On Diaries of a Loner, I was starting a journey to an unknown place. Birth of Santi came as I found somethings that would help me create the map for my journey. With Suzie’s Funeral, parts of the map are now clearer. I am in more control than I thought I was, and there are all these directions, left, right, u-turn, that I could go. Now with Mandy [& The Jungle] I can see the whole map.”

Ambiguity means possibility to Santi. He picked this up from how expansively Anime characters are woven into a cinematic narrative. He waxes lyrical about Light, the lead character In Death Note, one of Santi’s favourite shows of all time. Based around magical death note that can be used to kill people by scribbling down their names, Light, initially starts out as a principled good guy. He follows the footsteps of his father who was a police officer and only used the note to kill actual criminals. But over the course of the series, he falls victim to the corruption of absolute power, goes on a killing spree and even lets his own sister die to avoid exposing his own evil deeds. Santi does not only embrace this potential for duality in expression, he also allows his mind to explore possibilities for interpretation that deconstructs pre-existing stereotypes. As we start to discuss his Gothic-Nollywood inspired visual for “Freaky”, the first single off his debut album Mandy & The Jungle, he excitedly lists Tade Ogidan and Chico Ejiro as two of his favourite Nigerian directors who inspired him by pushing the boundaries of what is possible. His list of visionaries also includes controversial preacher and movie producer, Helen Ukpabio, who Santi used a clip from her horror classic, End of The Wicked, in the trailer for “Freaky” last year, to much criticism.

Mrs. Ukapbio rose to popularity in the late 90s for producing Christian supernatural-horror movies that started a wave of panic about child-witch cults in many parts of the country. She infamously published a book on how to identify child witches, where she claimed babies below the age of two who fall ill often or cry at night are possessed by demons.

Santi doesn’t make light of the allegations against Ukpabio’s legacy, but he staunchly advises me to separate the art from the artist in this instance, emphasising some of the universal themes of fantasy, rebellion and death of innocence that made her films wholesome instead. Whilst he doesn’t quite sympathise with her, there seems to be a hint of him relating to her, in the case of potentially being misunderstood by the Nigerian masses. Santi, as the de-facto leader of his peers, has taken the brunt of the skepticism for the growing Alté community, the latest: a ludicrous accusation of the promotion of cultism. In line with his tendency to stay in his cave, he doesn’t bite at the scandalous suggestions, or his comparison to pop stars in the limelight. He would rather let the music speak, like he always. “Everything will be much clearer when the album is out,” he states rather eerily.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Mandy & The Jungle is the title of Santi’s debut album, and with it comes the introduction of the latest character on Santi’s journey.

“Mandy is a story in itself, and the songs on the album are a soundtrack to the universe,” Santi explains. “There’s a girl called Mandy. She’s very quiet. Each day she waits to die, because she doesn’t have anything to live for. She thinks she’s going crazy because she keeps hearing her name. She doesn’t know she has this power over a whole legion of people.” Santi says the album is inspired by his belief in the power in the energy of women, and is a metaphor for gaining strength from within, something he has done his whole life. “You might think you are weak or powerless, but you have no clue the power you have inside you. That’s the world of Mandy & The Jungle.”

Santi emphasises the clear distinction between Mandy and his previous projects: already he has released three singles, with three stunning visuals to match. He’s also preparing comic books based on the album, which he wants fans to read to appreciate the full universe. He knows the pressure that comes with his debut album, but he appears to be relishing it. “I feel like I opened up a bit on this album,” he states candidly. “I wasn’t as vague or mysterious as I’ve been, I said things more clearly.” As excited as he is about the album and the content surrounding it, he tries not to get carried away with the increased popularity and aggressive label courting. He’s phenomenally humble about the interest, but he is not surprised.

Santi has been preparing for this moment his entire life; ever since he shed the sleeve of OzzyB, and birthed Santi; ever since he left Suzie to die, on the road to Mandy; this is the end of that journey, and simultaneously the start of a new one. He’s calm when he explains conversations with the president of OVO, and planning collaborations with Wizkid. He wants to go to Europe for the summer, and teach them Santinese. These are no longer the pipe dreams of the Osayaba that wrote serials for his classmates, this is his life now.

“The key to all of this, is days and days of experimenting. This didn’t just happen. i’m not going to sit here and tell you that.”

Santi knows what it’s taken to get here – and he knows what it will take to go even further. He’s always had his mind, his cave, his most familiar crutch in his time of need. But now, he has his ragers. As Santi has transformed over the years, leaving parts of himself behind, he has taken on more supporters, those prepared to fly his flag through hell and high waters. A quick look at the 6,000 strong crowd at NATIVELAND chanting the infectious chorus of “Rapid Fire” is just a glimpse into the army he has built.

Santi’s Rebellion is well under-way. Bend the knee.

![]()