uNder: Best New Artists (February 2023)

Featuring Kemuel, Rhita Nattah, Justin99 & more.

Featuring Kemuel, Rhita Nattah, Justin99 & more.

In recent years, we have been privy to several momentous occasions with the sounds from these parts incessantly redefining the status quo and breaking boundaries one track at a time. Now more than ever, spotlighting the expansive talent pool and variety of sounds emanating from this side could not be more critical. From the homegrown artists telling the stories of the streets in Johannesburg to the burbs of Abuja or Nairobi and even the artists emerging from the diaspora.

With a viewer attention span shorter than ever, some exceptional talents may skip your radar but the monthly instalments of our uNder column are here to ensure that all corners are covered. A month after bringing you artists that we expect to have a big 2023, we’re back with a new set of great, budding artists for uNder’s 2023 February class, with hypnotic sounds from South Africa’s viral Amapiano sensation, Justin 99, joined by the experimental synths from Flier in Kenya, the exuberant and introspective indie raps of Horrid the Messiah, plus more. Find your new favourite artist(s) below.

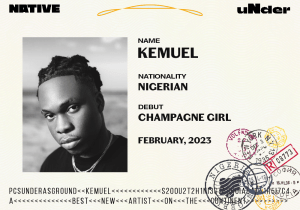

Earlier this year, Kemuel got recognition from some of the greatest in the game. It is telling that the duo of Spinall and Olamide allowed him space to establish the direction for “Bunda,” the lead record off Spinall’s sixth album, ‘Top Boy’. Beyond industry affiliations, Kemuel has shown glittering promise since the release of last year’s ‘ESCAPE’, a well-curated project which introduced him as one to watch out for.

Described as a literal escape from the restrictive shackles of realism, the longing for perfect union enlivens the project. Right from the ethereal sonics of “AWAY”, there’s an associative vibe to Kemuel’s sound. Not quite heavy in percussive tones, the colours of his singing meet the exquisite movements of Wondah, who produces the entire tape. “Can we run?” poses the song’s central tension, but between the reverb echoes of “away, away” and the inclusion of ominous elements, a lot of sonic layers unfurl. “FINALLY” and “MUMU” reveal similar sensations, Kemuel’s vocals ever poignant and coloured with bases of hums, strings, call-and-response patterns. Unhurried, it’s the type of Afropop CKay and Victony gets consistent props for, although Kemuel’s language is distinctly his, not quite risqué as the aforementioned names but tender, serenading with his milky vocals.

As a child, Kemuel loved to play with choir instruments, enabling a grasp on the rudiments of sound. In 2021, his production for Sukah’s “Spotlight” showcased the atmospheric elements he’s now immersed in. The titular record of that EP—and also the last—demonstrates Kemuel’s appeal: affectionately scripted, the laidback grooves radiate with purpose and passion. Over time we’ve seen artists that produce make great music, and Kemuel seems to have so much in the bag. His journey burns with promise.

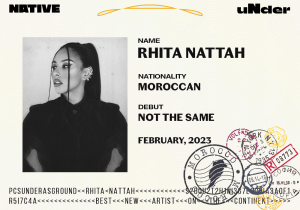

One of the most striking qualities of Moroccan singer Rhita Nattah is her voice; it bears so much emotion and charisma. The next thing that catches your attention is her lyrics, which shine with insight from lived experiences. Although she has been in the music industry since 2016, Rhita Nattah released her first single “Not the Same” in 2019, in partnership with long-time collaborator Samir El Bousaadi. She and El Bousaadi, since the days of her Afrobeats-themed covers, have spent time learning production and songwriting and crafting a sound that is both ancient and contemporary.

“I gave up on everything for the music, and made bloody sacrifices in Morocco to be able to create it,” she tells the NATIVE. “In Morocco, there’s no music industry and artists don’t even get paid their royalties from organisations. Samir El Bousaadi and I used to have two eggs per day and create music. Even though I had a master degree in French didactics and he was working as a graphic designer director, he gave up on his work to live doing his passion, because we can’t imagine ourselves doing something else.”

In early February, Rhitta Nattah released ‘INNER WARRIOR,’ a documentation of her journey and experiences, as regards love, self and Moroccan society. Effortlessly, through traditional Moroccan music, R&B and Soul, she makes room to vent her angst, embrace her vulnerabilities and call out her country’s politicians. “I am gonna tell you things about myself/I didn’t know before/Things I hide from myself, from myself/Oh, some days were dark,” she opens up on “Garden” off ‘INNER WARRIOR.’

“Counting all my blessings, I’m not willing/To give up on my soul and my sanity/I have faith in my words and their honesty,” she sings on “Fear Nothing,” revelling in her inner strength. “I want to be a voice for the people, a friend, a sister, through my music and words,” the singer tells The NATIVE. Rhita Nattah is a voice that will be heard for a long, long time to come.

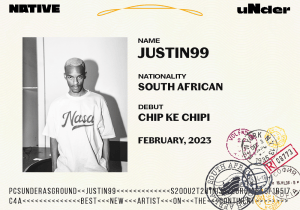

The intoxicating log drums and sweet-sounding shakers, accompanied with the heart warming melodies commonplace in Amapiano have become a comforting sound for most listeners privy to South Africa’s burgeoning scene. Ever so often, artists like Justin99 discover new ways to transform the transcendental ‘piano sounds and facilitate an even deeper connection to the listener, devoid of language barriers. Framed within the digital age, a viral moment for an artist like Justin couldn’t be more perfectly timed and well deserved. While many may recognise his 29-second snippet for the #Justin99Challenge, accompanied by striking dance moves from a number of Tiktokers, Justin99’s discography holds other notable tracks.

His debut, “Chipi ke Chipi,” off Amapiano hit-making producer-duo Mellow and Sleazy’s ‘Midnight in Sunnyside’ couldn’t have been a more perfect entry into the scene, a chippy viral hit song with over 2 million plays on Spotify alone. Doubling down on stellar collaborations, Justin99 enlisted Mr JazziQ, Pcee and EeQue for a catchy, thumping rendition on “ZoTata,” alongside “Mozambique” and “Dlala 99,” off the Volume 2 compilation of South Africa’s Black is Brown Entertainment album. From his small but mighty catalogue and snippets of future collaborations with Amapiano heavyweights like Kabza De Small, the producer, DJ, dancer and vibes curator has proven to be a promising act to keep an ear out for.

View this post on Instagram

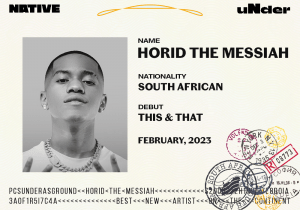

Intricate songwriting has always been a forte for rappers. Listening to Horid The Messiah, the South African rapper’s formative diet of classics from older relatives and the contemporary model of A-Reece is revealed through the strength of his pen. Horid began releasing material two years ago, pairing glossy, trap-suffused production with narrative zest. The October 2021 debut EP, ‘I V T A P E S’ had four tracks under a runtime of ten minutes, but it was enough time for Horid to flex tightly-scripted bars and exuberant deliveries, with themes like self-belief and romantic fissures scripted with visceral ability.

The Johannesburg-bred rapper continued to forge on, his tendency to collaborate with fellow rising acts—Kaz, Eddie Soul, fellow uNder alumni Scumie—burnishing his credo amongst a community of like-minded folks. Horid’s sobriquet as ‘Baby Jesus’ might reference his diminutive stature but it’s also a reflection of his complete appeal as a music superstar. Modelling and acting for brands, he’s got one foot in the corporate world while the second roams, enabling stellar releases such as “I WON’T TELL” and the ‘While You Wait’ project, both in 2022. “HURT” was the latter’s opener and an indication the rapper sought to probe the greater demons of his mind. “I don’t condone all the shit that I’ve done, this is something that you don’t deserve,” he raps over a thinly sketched production. An immersive project advancing the shock value of glitz, The Messiah’s humane quality comes alive.

Horid walks on a path trodden by the likes of Reece and Nasty C, rappers whose pop-leaning direction does not diminish their dedication to street narratives. The Solo Sae and Ficz-assisted “UHHH” also marked a great start to the year, its distinct cadences and synth-heavy production endowing the record with ostensible hit qualities. Horid The Messiah’s fine range is demonstrated most recently in his Valentine’s Day-released two-pack ‘Do 4 Luv’, baring, at this point, his double-edged sword of boisterous cuts and soulful introspection.

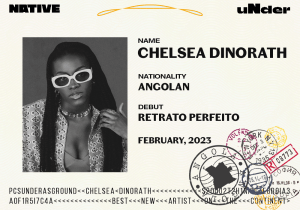

There’s an obvious sensuality to Kizomba music that lends itself the best to affectionate performances. For a genre whose popularity cuts across multiple continents with Lushophone ties, there’s no shortage of great vocalists and there’s always an influx of fast-rising talent, who understand the music’s form and how to function within it. Angolan singer, Chelsea Dinorath is on track to become Kizomba’s latest superstar, delivering earworm jams with heartfelt intentions.

Even though she’s been making music for much longer, she officially debuted in 2019 with “Retrato Perfeito,” a mid-tempo song where the building blocks for her artistry can be heard in hindsight. In subsequent years, she followed up with diverse singles, going the contemporary R&B route on “With U,” singing in multiple languages on “Toi Et Moi,” and contributing a lilting half-verse to the ensemble cast hit song, “Céu Azul.” While a large part of the last couple of years could be described as her development stage, Chelsea Dinorath is officially in full bloom.

With her richly textured, siren voice and a writing style that boils down the tension of romance into gorgeous songs, the singer’s abilities have been better realised over her singles from the past year. It’s no coincidence that it comes with her full lean into Kizomba, like the winning warmth of her biggest song yet, “Sodadi.” On “Melhor,” log drum infusions accent the buttery groove, showing her willingness to innovate within genre boundaries. Chelsea has already opened her account for 2023 with “Unfollow,” which emboldens the effortless beauty of her voice – a striking artistic trait that will help carry her to greater successes.

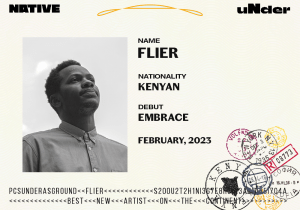

Flier describes himself as the “purveyor of all things fly.” There’s an enveloping serenity to a Kenyan singer, rapper and producer’s music, where personal dispatches take on a relatable warmth. On “Filthy Rich,” his vocals and minimalistic production choices invites you into his world where he sings his admiration of being rich and being able to make it out.

Singing and rapping in both Kiswahili and English, his voice cuts across the chorus with the first verse being a dedication to his family and the second verse to his romantic muse, both of which he promises the world to them. His singles are often paired with distinct guitar productions as seen in “Embrace,” “Policy” and “Kile Tumepitia.” The most exciting part about Flier’s career is his ever-diverse creativity which sees him explore diverse subjects. Whether it’s love as seen in “Bandia” or just teasing his production skills in “Run Deputy Run,” which carries clear inspiration from Bob Marley and the Wailers’ 1973 hit, “I shot the Sheriff.”

With a limited digital footprint and a sprawling catalogue of singles that stretch back four years, Flier is yet to hit a mainstream breakout moment but he doesn’t seem keen to break the mode of his operations, seemingly trusting that the music will find its intended audience. Flier’s music found us, let it find you too.

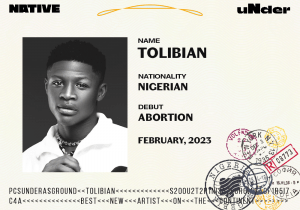

Nigerian street-pop is fond of elevating viral stars with veritable talent. (See: Zinoleesky.) Ilorin-raised Tolibian first popped on Nigeria’s youth culture radar with a series of ear-catching, humour-tinged covers of popular pop songs, with the most notable arguably being his cover of Buju’s “Peru (Refix)”—itself a cover of Fireboy DML’s global hit song, “Peru.” Those covers exhibited the influence of Apala on his vocal tricks, which is fitting since the genre of Yoruba folk music has a deep history tied with Ilorin.

In 2021, Tolibian officially kicked off his journey with his debut single, “Abortion,” a fine display of his ability to deliver songs relaying the Nigerian experience, delivered in a winning mix of pidgin English and Yoruba quips. He’s followed with several well-received singles, setting himself up as an accessible voice in street pop without losing the winning charm of his earlier covers. Even as his voice and style is heavily influenced by Apala, there’s a very modish tilt to Tolibian’s artistry, even approaching the R&B-influenced side of Nigerian pop with songs like “Abaya Palava” and his most recent lovestruck single, “Hello.”

Over the past two years, Tolibian has converted internet listeners into fans with his voice of gold, and the potential for stardom is brighter than ever. With a knack for blending catchy Afropop rhythms with soothing R&B melodies, Tolibian is one to look out for this year — a fresh new voice of the generation we’re looking out for this year.

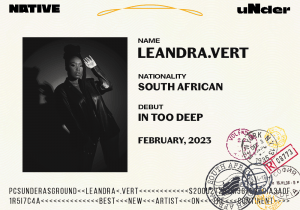

In November, South African Amapiano producer/DJ Musa Keys spearheaded the eponymous release of his label’s debut compilation project, ‘House of TAYO’, packed with contributions from emerging artists on the imprint’s roster. On this compilation, singer Leandra.Vert quickly showed out as a standout performer, turning in indelible contributions across the four songs she’s featured on. With her cherubic, positively dizzying voice, she floats over the saxophone-infused “AboMalume” and adds an ethereal dimension to the project’s commercial centrepiece, “Blue Tick.”

Before her House of TAYO affiliations, Leandra.Vert was already flaunting her potentials as a singer, mainly opting for soulful pop and R&B soundscapes on earlier singles, including the 2021 debut song “In Too Deep” and early last year’s “Tse Monate” with Mustbedubz. Both love songs, they served as an introduction to her raw vocal talents, which she’s been harnessing better with subsequent releases. Drawing inspiration from a range of artists, including current neo-soul luminary Ari Lennox and soul-fusion rule-breaker Iamddb, the singer has spent ample amounts of time perfecting her craft to fit varying sonic moulds, with Amapiano being the current focus of her sound. The sample size isn’t huge, but Leandra.Vert is already an artist to pay attention to.

Compiled and written by Emmanuel Esomnofu, Uzoma Ihejirika, Nwanneamaka Igwe, Wonu Osikoya, Tela Wangeci & Dennis Ade Peter.