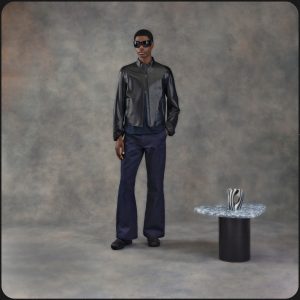

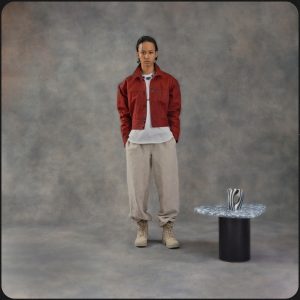

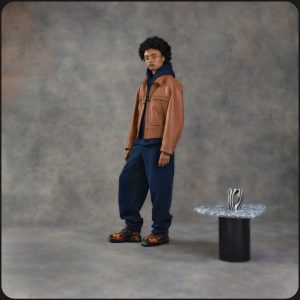

NATIVE Exclusive: Adémidé Udoma wants to be Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

The designer and creative director discusses the importance of time and unconventionality

The designer and creative director discusses the importance of time and unconventionality

One of the first notable things in the showroom for ABAGA VELLI’s debut, ready-to-wear collection was not one of the many uniquely crafted garments presented. It was the bag of fresh flowers displayed in a bag in front of the entrance. Creative director, designer and brand co-founder Adémidé Udoma says he specifically asked that there be no water for the plants, wanting to show their full life cycle and eventual decay. This was an early indication of the way Adémidé approaches his designs, with thoughts about the entire journey of each item, and the brand as a whole.

Perhaps this focus on journeys stems from the fact that he has had a significant one in his own life. While Adémidé was born to Nigerian parents, he spent his formative years in the UK. He grew up experiencing the artistry that London had to offer, making frequent visits to the vintage fashion haven that is Brick Lane, where the showroom took place. He was also exposed to British history, both through school and simply by growing up in a historic city. He, however, did not have as much access to the details of Nigerian history. He had to go out of his way to get information, in the amount of depth he wanted, facilitating a proactive nature in doing research on the topics important to him. This active curiosity was not just limited to history, but to all sorts of artistic mediums. He was inspired by literature, like the work of Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka.

This interest in various art forms led to an unsurprising foray into the creative industry, with Adémidé gaining years of experience working as a creative and art director with various artists and publications. With a history in fashion already, making made-to-order items for various clients, he is going into ready-to-wear for the first time. The recent collection, COUP 001: All Roads Lead to the Horn, promises a great future for the brand. Adémidé tells us The NATIVE he is already thinking about the brand’s 100th collection, with the entire journey of ABAGA VELLI in mind.

View this post on Instagram

Adémidé is also currently designing furniture, notably making tables out of recycled material. He is someone that thinks about how long things can last, and where they will end up. This is represented by the second part of the collection title, As All Roads Lead to the Horn, which references the idea that all roads lead back to Africa, his origin. In thinking of endings and beginnings, God warned Adam early in the Bible, “For dust you are, and to dust you shall return”. Adémidé is thinking about where the items will end up, allowing for a focused approach to sustainability, which likely plays into his goal of his clothes being as timeless as possible.

In the room, across from the waterless flowers, there were a pair of shoes displayed in the middle of their design process. While the shoes may simply seem unfinished at first glance, they are also a complete art piece in some ways. Likewise even the completed items in the collection are in the middle of their own journey. Things existing in different states at the same time. Even though the journey of ABAGA VELLI started a while ago, this really does feel like the Genesis of something completely new.

NATIVE: ABAGA VELLI means ‘Art Brings Access, Grants Ascendance’. What do you think art can bring access to? Where can people ascend to through art?

Adémidé: The bringing of access just represents the idea that, through my time and through a lot of my peers’ time from humble beginnings, our work and our talent and our skillset has often granted us access to new information and to other platforms of information. So every single time I’ve been able to progress my mindset and elevate through our work, it’s allowed me access to new rooms, people and environments. The grants ascendance side is, through this access I’ve been able to, and I hope others will be able to, access more and elevate and ascend to these higher thought processes rather than seeing your life as very much decided for you, just like through your expression you’re always able to evolve out of that situation, your current is never permanent.

What made you make the transition from made-to-order to ready-to-wear? Why is now the best time for this?

The transition very much stemmed from demand to be honest. At the beginning it was very much about developing, exploring new tailoring ideas, new forms, new shapes. Very much a honest way of communicating visually. Then from that using that in shoots, I was able to build a following and a real cult demand for what we do, and at first we responded to that demand through made-to-order commissions. But after that, it transpired into becoming a full-fledged brand. And then we had buyer interest and that was one of the key things that made me and the team decide that we do need to offer a full-on collection so that people will understand how everything works together, rather than just positioning a jacket or one pair of trousers as a thing you can buy from one of these retailers. We thought it was important that purchases weren’t just based on what they saw a certain artist wearing, that it was based on a full collection.

Was it always the goal to evolve into a ready-to-wear brand? Or was it just based on the amount of demand?

It was definitely organic. Approaching it in this way, like working with stockists, wholesale—all these types of things were initially in the thought process. It wasn’t like, “yeah we’re doing this to sell to retailers,” that definitely wasn’t the case. For me I always wanted to create a gallery project, and I still eventually want to do that. Eventually we’re going to have a direct to consumer offering and that will be a full-on gallery platform, rather than just a clothing brand. For now I guess the way the stars have aligned has allowed us to work with stockists, and introduced the brand to a wider audience.

You’ve said your brand has a ‘nomadic diaspora nature’. How much of your brand is linked to your identity as someone in the diaspora?

I think it’s limitless, to be fair. Every part of that is a factor. For me growing up at a young age in London but still having this connection to Nigeria and to my culture, and even within my culture, starting to understand the nuances of different tribes, was a very confusing upbringing so I had to kind of navigate Britain. Being in this society and trying to succeed within that construct, while still knowing that I was an outsider and not really ever feeling that national pride that some of my school friends would have about England. A Lot of that restriction has always fuelled my creativity, it’s always made me want to express myself and be somewhat rebellious. I’ve been fortunate enough to find skillsets that allow a lot of that rebellious nature to stimulate progression rather than turn that into something that could have been very negative.

So, for me, this diaspora element and the idea of being born a foreigner and never feeling like you have a fixed home, making the world your home and feeling like you’d be able to go to anywhere in the world and really take something from that experience, whether it be going to Rio De Janeiro or Bhutan or Italy. It’s always had an impact on my work so even with the clothes you’re going to see certain details from Italian tailoring and fabrications from Japan. You’re going to see Yoruba hand craftsmanship that would be accustomed to like woodcraft. You’re going to see certain elements of my fathers side, which is the Ibibio side, and they are very much sea people so you’re going to see certain fisherman types of nods. Because I’m of the diaspora, my nod to fisherman might be a utility vest or a waistcoat because that’s still a very European way of approaching fishing culture.

I still think there’s a beauty in that because, through these experiences I’ve had trying to go back home or trying to get back in touch with my culture, I still have to have an element of that diaspora to be able to even communicate it. All these different elements have come together to create this beautiful noise of expression. Through not feeling at home in the country I was born in, I’ve always looked to other cultures. That’s actually a big element of the idea of All Roads Lead to the Horn. No matter where I go or what I try to seek, I still end up en-route back to my origin. That’s really the main thing in regards to the references. I’m always seeking something different to the norm. My norm is already something I feel distant to. When you question your origin there can be so much depth to that too, even when you go back home, in my case Nigeria. There’s so much lack of understanding because a lot of those things actually aren’t Nigerian, there’s a lot of ideology that was brought over from elsewhere. You can even be in the diaspora in your own country. For me when you’re going on this journey back to the horn it’s just this idea that you’re learning more information from all these experiences to reach an understanding within yourself rather than having to be in a specific place.

What’s your ideal journey for a clothing item of yours to take?

Everything that I create, I want to last multiple lifetimes. The most fulfilling thing would be to know of a piece that I created being passed to someone’s child. And their child’s child could have the same jacket, with it becoming a family heirloom. That would be the most fulfilling thing, to have work that outlives me and outlives people. That could end up in the most interesting and outlandish places. Time is something I’m very interested in and the idea that items could become more powerful the longer they are, rather than when they’re brand new or fresh off the press. It’s very much that the value comes from the time, the stories and the journeys that have latched onto the garment rather than just the creator and being made. That’s when it becomes a vanity project. Like, “Oh, I made this so it’s the best thing ever.” It’s only the best thing ever when it’s lasted the test of time. I’d say the goal is for my clothes to be timeless.

How has your past as a creative director impacted your design process?

I approach everything from storytelling. I don’t see a difference between designing clothes, designing furniture, writing films and styling. I see it all as the same thing, it’s just different mediums of communication. I guess through creative direction, from a commercial standpoint, has allowed me to understand the importance of understanding your audience and showcasing your messaging in a way that can be understood. A friend of mine told me a quote: “The idea behind songwriting is to say the most with the least words.” That’s how I see creation. With clothes you can write books, it can be a lot but to stimulate a reaction just from looking at an object is such an interesting thing. When I creative direct for brands, a musician, a record label, it’s still the same thing and them being able to get the message across to the audience. I guess that’s how it’s helped me. It’s helped me perfect my craft of communicating to an audience.

What single piece of media has had the most impact on you and this collection?

It’s hard for me to say one piece of work to be honest. But I definitely think that critical literature in general has had a very big impact on me. I’ll also say directors like Jean Luc Goddard have had a very big influence on me. I guess it’s not really about this collection, it’s more a nuanced amalgamation of ideas. I wouldn’t be able to say this collection is because of this. It’s very much a life journey being put into clothes. I definitely would say between music and literature, definitely not actual clothes, those two things have inspired me to be able to do this collection. But it would be unfair of me to say a specific song or book. I’m very much an extract person. I may read your whole book but it’s just one paragraph that’s changed my life.

Why is it important to bring a casual touch to formal clothing constructs?

It’s just the idea that I want someone to feel comfortable in any environment. A Lot of the time you can feel that, to be in a formal environment, you have to conform an element of your identity. But, for me, I want to create clothes that can stand the test of time and the test of environment, so it’s multi purpose. That’s actually a lot of where the utilitarian nature and the military references stem from, because a lot of those military pieces were made to work in all kinds of terrains. For me to be able to be at a wedding or in a meeting and be in a suit, but the suit feels as comfortable as wearing a denim jacket—that’s the same kind of concept. That you can go to a night event or a house party and you can wear the exact same outfit, maybe styled a little differently depending on your preference, but it’s still really the same thing. It’s allowing the clothes to be multi-functional. It’s very much about the user as much as it is about the clothes; the clothes don’t make you, you make the clothes, so it’s really about yourself and how would you want to rock them and that’s your style.

You’re someone who likes to challenge your consumers. Do you feel that making your clothes so flexible to different personalities offers its own challenge?

I think it’s a challenge because it takes a lot of time and a lot of tailoring. What I’ve been able to understand from being around bespoke tailors for the last ten years, I’ve understood that a successfully tailored jacket is about it being comfortable to the wearers and not just looking striking to the viewer. That really is the difference between ready-to-wear and bespoke, because you can buy a very expensive ready-to-wear jacket from any serious ready-to-wear brand, but it will never feel the same as a bespoke version of that jacket just because of the way that human bodies are all very different in very specific ways. So, for me, it was the idea that understanding human form and putting clothes on so many different types of people and trying to find a good medium. It took a lot of time to get to that point but I feel like it will complement a wide variety of body shapes, from men to women to anything.

It’s never about the sex, it’s just about how it falls. I don’t actually see it as menswear or womenswear, I just see it as how the clothes fall. It was hard but definitely I feel far more confident by having to do it the hard way, because now I have something that I feel is actually quite forward-facing and innovative just from the tailoring side alone. I wouldn’t even say it’s a challenge, I feel like it’s quite fun, it’s a collaboration. And I’m very excited to see how people are going to wear it independently because, as you can tell, everything was pretty much styled by itself. That’s going to excite me and probably even inspire me more with my next designs, it’s probably going to be like, “Wow, I didn’t even think about it like that, that’s crazy.” Definitely, it’s going to be a conversation between the customer and myself.

You say you already have a plan for your 100th collection. What would this look like?

Yes, but it’s not so literal in that way. In terms of line drawings, I have hundreds and hundreds of them. A Lot of them are super technical to the point where I have no idea how I’m going to make them in real life. So it’s me on this journey to make what could be considered the 100th collection, but it’s more like a concept car. I’ve already designed the concept building but before I get to any of those things, I first have to find out how I’m going to make the trouser and the jacket. For me, the collection I’ve designed already, those are definitely the aim to get to. But nothing is so linear, everything can come in. But I definitely create the clothes in a way that they are going to be elevated. I’ve stripped them down so there’s so much more of the journey to go on. It’s kind of like a musician exposing the stems of the track. You’ve got the stems so you can make all these different outfits and remixes but I’ve already got the mastered version in my head, I just haven’t put it out yet.

What was the most challenging part of putting “COUP 001: All Roads Lead to the Horn” together?

People! [Laughs] I don’t want to say it like that, but it’s just friction. At the end of the day, when you’re someone who’s a bit of a dreamer and very ambiguous, ambitious and abstract, people can kind of be like, “This doesn’t make sense.” It’s hard, but people have to see things fully before they can really understand it. A lot of times I’ve had friction just by having to dilute things so they can be communicated well enough to get to the next level. That’s part of design and something that I’ve learnt, even through client work, is that understanding your client and collaborators is important, because at the end of the day it’s not just you, you need people. So I guess that’s been the hardest part, having to be dependent on people and having to go back and forth to make sure they understand what you’re saying. It’s been the most difficult part but also the most fulfilling because, at the end, when you make something that you consider beautiful, all the fighting and back and forth is all worth it. The back and forth does help ideas evolve. Pressure makes diamonds.

What does it mean to you personally and as a brand to debut at London Fashion Week?

I think it’s very progressive. I’ve always been into fashion so I’ve always been aware of these types of events. It’s quite interesting just from the fact that we, who are very unconventional, are able to be on these conventional platforms. I think there’s beauty in that type of disruption. There’s a coup in it [laughs] because I’m sure there’s many people who wouldn’t want us to be in such places. For me, it’s a testament to the collection itself, it really is a coup. Now we’re in the room. I don’t want to over-attribute things to these platforms, because I don’t want another young designer reading this to think they have to be on these platforms to be legitimised, but it is nice to be there and show more people your approach. I appreciate that but I definitely don’t think it’s a necessity. There’s never an only way to do it.

What’s next for ABAGA VELLI after this LFW debut?

More editorial, collaborations, films and of course more designs. I really want to explore the idea of a creative eco-system; gallery, workshop, store, and culinary experience.

What’s one thing you want ABAGA VELLI to be remembered for?

I want the ideas and works to continue to evolve, and following generations to use our unconventional approach as inspiration to not have to conform their ideas, and that there’s always another way.

[All images provided by ABAGA VELLI via FUTURE BRAND THINKING]