Examining the history and value of African hair

My hair is my crown, don't touch it.

My hair is my crown, don't touch it.

Black people are some of the strongest in the world. We are so strong, that we’ve become accustomed to hatred and profiling, adapted to this reality and continued to thrive in the midst of oppression. I always wanted to grow my hair out in secondary school, and this desire was fueled mainly by the need to stand out because everybody having the same buzz-cut just wasn’t fly.

To our adult guardians, however, grown out ‘bushy’ hair made us look irresponsible, and school policy in Nigeria enforces harsh punishment on male students with outgrown hair. In my secondary school, public humiliation was the punishment of choice and teachers would gleefully use scissors to ‘decorate’ (read destroy) full hair on male students. With unsightly cross designs, we never gave this demoralizing act much thought, but we all felt this treatment was completely unjust. The reasoning behind this was aimed at making students appear ‘presentable’, and I always wondered why the hair on our heads was deemed so unattractive, and more importantly, why is there so much focus on a natural part of our bodies?

The need to look clean and presentable is a paramount concern for most people, evidenced by the multi-billion dollar cosmetics industry worldwide. The black hair industry is valued conservatively at around $2.5 billion, with black entrepreneurs only accounting for 3% of total ownership of products marketed to us.

Growing your natural hair as an African person always attracts so much attention, both at home and in foreign lands, and certain styles are seen as serving a deeply rebellious or creative purpose. Whilst one optimistic side would like to believe that this is a testament to the gracious beauty of our lush hair, it is in reality, more closely related to ingrained self-sabotage, and propaganda remnants of slavery and colonialism.

Prior to colonialism and western oppression, Afros and different African hairstyles were used to distinguish and identify people on the basis of their tribe, occupation and societal status. Beyond being a natural aspect of African beauty, African hair and its unique texture sets us apart as a race, and its delicate nature requires deliberate and specific attention. European explorers and their governments in a bid to assert racial domination went as far as fabricating scientific data to prove that the African man was a lesser human, all in a means to justify the ‘civilization’ of Africans.

Using humiliation and psychological warfare, the Europeans facilitated propaganda to ensure that Africans hated every aspect of themselves, issuing draconian policies in Africa, with the help of local leaders, and severing the proud ties transatlantic slaves had to their motherland. Slaves were not allowed any personal belongings(or even clean water), including their instruments of hair maintenance, resorting to using grease to lubricate their hair, and using metal ornaments used to groom sheep to comb their hair.

Over half a century since the independence of most African nations, and close to a full century since the abolishment of slavery, the psychological remnants of subjugation and self-hate are still present in African communities. Natural hair is still not embraced, and a lot of people still maintain conservative opinions about traditionally hairstyles African styles, despite the resurgence of natural Afro-hair philosophy.

You might be tempted to see these perceptions as exaggerations, that can’t really cause much harm, but you would be wrong. As hair forms an intrinsic part of identity, it’s appearance to some, can lead to harmful perceptions, particularly towards women of colour in professional environments, who go through so much to just be treated like everyone else. Our perceptive nature observes these subtle cues in society, and eventually normalise harmful definitions of our standing in the world.

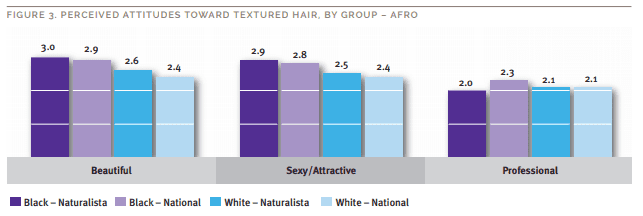

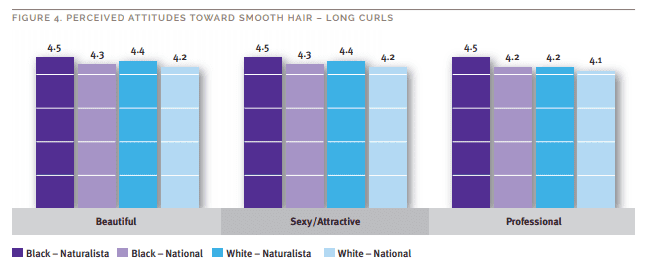

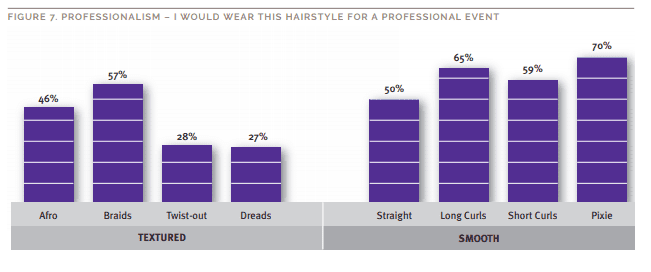

A 2017 study titled The “Good Hair” Study examined the explicit and implicit attitudes towards the hair of women of African descent in the US, and found that not only was the Afro hairstyle viewed as being less attractive on average, it was also seen as being less professional when compared with long, straight hair. Most black women favoured straight or long curls against braids and afro hairstyles.

Within the survey, the question is posed about ‘Hair anxiety’, also revealed that women of colour also face more anxiety about the appearance of their hair. It is even more difficult to analyse the perceptions of African male hairstyles in society and professional settings as most black men favour shorter haircuts.

Perhaps this has always been the case through history, but there is evidence to support the prized nature of male hair in African society. An interesting piece of anecdotal information is that most black men with longer hair – often locs or braids – are assumed to be athletes or creatives, perhaps because these fields have less rigid dress codes. A male friend of mine who had locs recently cut his hair, and when I asked, he simply remarked ‘you can’t get into corporate doors’. We both work in Lagos.

The discrimination against hair in the west is often seen as being racial, but the negative notions of what natural hair entails back home are still just as firmly entrenched, and rarely examined. In South Africa in 2016, female students of a Pretoria High school protested against proposed school policy that targeted African hair, requesting students with Afros to straighten their hair. This policy exists as a standard principle of most government schools in Nigeria.

This is particularly concerning, as an important aspect of education is guiding students to be comfortable with themselves and appreciate their natural qualities. As we continue to dismantle the aspects standardised racism in our societies, it’s important for us to protect our future generations from the dangerous notion that their hair is not good enough, and hopefully equip them with the history to confidently appreciate every part of their natural beauty.

Perhaps this might inspire more research and development of more African-owned hair care products. Cosmetics is not vanity, it’s the first and most obvious manifestation of personal identity. I hope that more of my male and female peers are inspired to embrace their natural beauty, in their natural hair. You cannot teach a person right or wrong, but you can teach a person how to treat you, and responsibility must come from home first. Until we as Africans and members of the diaspora celebrate, learn and teach the history of our hair, we cannot expect the rest of the world to lead that crusade for us. All people are born free, free to live and maintain their hair in whatever means they deem fit.

Featured Image Credits: Web/ Perception Inst.

[mc4wp_form id=”26074″]

Djaji is a creative Vagabond, send him your takes on music and African culture @djajiprime