In Africa, the vinyl record has always had its place, much like the well-travelled and eccentric village elder whom not everyone understands, but everyone respects. Once thought to be on the brink of death —as rapid technological advancements diminished its popularity in the 90s and 2000s—vinyl records have made a remarkable comeback, with sales rising steadily over the last 15 years.

According to Cognitive Market Research, the Middle East and Africa had a vinyl record market share of around 2% of the global revenue, with an estimated market size of USD 45.08 million in 2024. It is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.3% from 2024 to 2031. Such consistent growth in one of the world’s most volatile industries is really quite impressive. But, to borrow music producer Marco Sebastiano Alessi’s words, “trying to represent such a complex ecosystem simply with numbers means offering a partial perspective on one of the few niches in the music industry that’s thriving, both in terms of numbers and cultural impact.”

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, demand for vinyl records is also on the rise, thanks to the rise of cultural hubs, vibrant online communities, interactive vinyl festivals, and immersive listening sessions. Existing independent record stores like Mabu Records in Cape Town and Torobee Distribution in Dakar that once struggled to stay in business are now gaining traction, while new stores like Ritual (Accra) and Broken Records (Windhoek) open in cities around the continent, selling pre-owned and reissued copies of legendary records by beloved African artists like Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Ebo Taylor, and the Lijadu Sisters.

But what’s the real secret behind the vinyl record’s longevity? How did it retain its cultural foothold in Africa? And, as we advance further into the age of AI, what does the future hold for this beloved form of music?

Vinyl As A Journey Through Time

When major international labels like His Master’s Voice (HMV) began releasing commercial recordings of East African musicians in the 1920s and 1930s, most of the records were pressed internationally and then shipped back to Africa for sale. It wasn’t until 1952, as Kenya’s independence struggle gathered momentum, that the first physical vinyl pressing plant (East African Records Limited) opened its doors, transforming Nairobi into a vital musical hub for African artists.

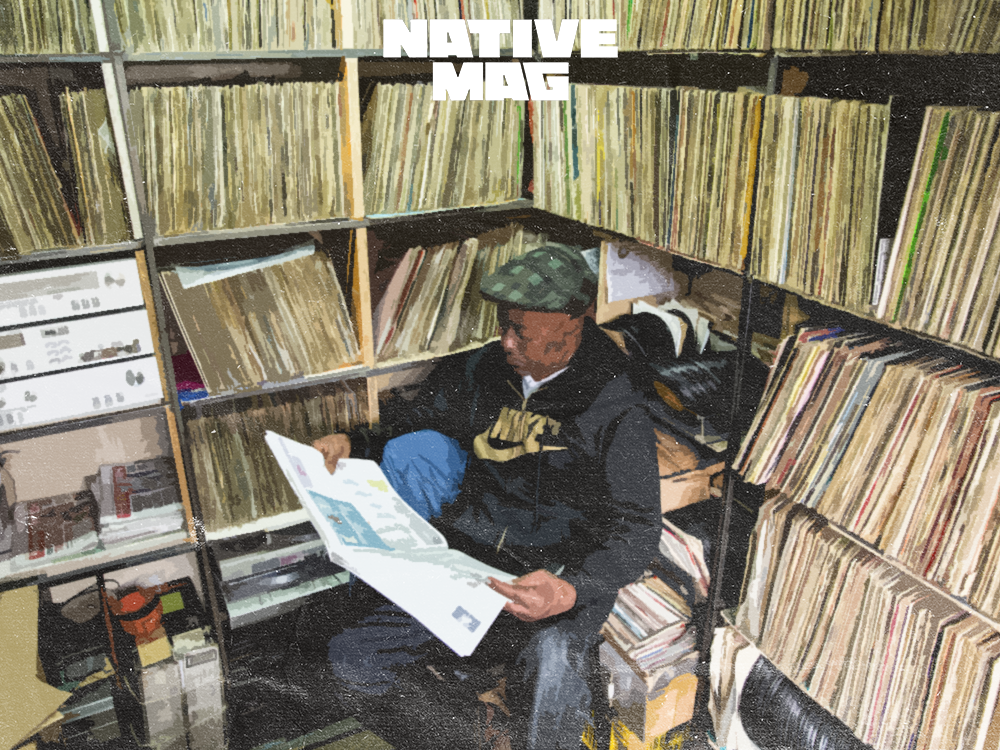

Today, Kenya’s lush vinyl history is kept alive by custodians like James ‘Jimmy’ Rugami, whose treasured record shop in Kenyatta Market houses one of the country’s rarest vinyl collections. Pheello ‘PJ’ Makosholo—South African music lover, vinyl aficionado, and founder of the Collectors’ Collective Record Bar in Johannesburg—describes such dedicated vinyl collectors as “living museums,” likening the crate-digging process to important archaeological work. “The role of the collector should never be understated because when record companies stopped valuing our music, the collector still found it important and listened,” he says.

South Africa’s history with vinyl began between the 1940s and 50s, with major pressing plants like Trutone, Gallo, and EMI emerging in Johannesburg to meet growing demands. By the 1970s and 1980s, the LP vinyl had cemented its place in the country’s music scene, expanding to include local genres like Maskandi, Kwaito, and Kwela, with luminaries like Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela gaining more global recognition.

“The records in my collection that are from the SABC archive [some of which were censored during the Apartheid regime], or those stamped records from Ray Nkwe’s collection, are really special. He was the go-to for finding international Jazz records, as well as a prolific producer of legendary South African Jazz and Soul albums such as ‘Inhlupeko: Distress by the Soul Jazzmen,’” says sound selector and multidisciplinary artist AK Jenkins, whose newly opened vinyl store, Play The Crates, serves as a sonic bridge between the past and the present.

Over in West Africa, Ghana’s rich vinyl history began around 1928 with the recording of Highlife music by colonial companies like Zonophone. This brought the genre and beloved artists such as the Kumasi Trio into the limelight. In 1948, Decca Records opened West Africa’s first recording studio in Accra, which led to the production of numerous classic Highlife songs through the 1950s and ‘60s. The vinyl industry blossomed after independence, with the establishment of the state-owned Ghana Film Industry Corporation (GFIC) in 1964, and private companies like Philips Records all contributing to its growth.

“There are so many elders today who have extensive vinyl collections that they don’t know hold great value,” says Ghanaian writer, cultural researcher and DJ, Kobby Ankomah Graham. “Without vinyl, Ghana would be in the musical dark. It’s also worth noting that Hip-Hop has a massive impact on modern Ghanaian music. Vinyl DJing is the first of the four elements of Hip-Hop, without which that genre would not exist, so modern Ghanaian music owes a lot to vinyl.”

Of course, no conversation about West Africa’s vinyl history would be complete without mentioning Nigeria, where Josiah Jesse Ransome-Kuti is often credited as being the first artist to release a gramophone record of Yoruba hymns in 1925. Decades later, Lagos became an epicentre for music innovation and production, with international companies like EMI setting up studios through the 1950s to 1970s. This “golden age” saw the rise of Highlife and the emergence of Afrobeat, with many groundbreaking albums released on vinyl by the likes of Fela Kuti and the SJOB Movement. By the late-70s, world-renowned record labels like Afrodisia Limited took the Nigerian music market by storm, ushering in a new era of Nigerian-owned enterprise.

Sadly, as the 1980s gave way to the ‘90s, vinyl lost its prominence in Africa (as it did globally), as cassette tapes and CDs offered listeners greater convenience and portability.

Vinyl As Legacy

When newer music formats started taking over in the late 1980s, local and global vinyl pressing plants began to close down. Today, there are no active large-scale vinyl pressing plants in Africa. In fact, the continent’s last known major pressing plant, a sprawling facility located in Harare, Zimbabwe, was sold to international bidders for about £160,000 in 2015. Owned by the now-defunct South African label Gallo Record, and once part of a flourishing network of African vinyl factories churning out homegrown classics, the plant ceased operations in the early 1990s, laying dormant (but well-equipped) for several years.

Makosholo mourns this loss, calling the sale a miscalculated and short-sighted move: “The saddest thing about the vinyl world right now is that we’re once again dealing with the colonisation of African music, which is taken out to Europe, and then sold back to us at exorbitant prices.”

Although this is a highly contentious and nuanced issue, it would be tone-deaf not to mention it. The fact is: Africa’s most cherished sounds, particularly those from overlooked regions, regularly sell for four figures on record-collecting sites like Discogs. Devoted crate-diggers like Makosholo want to reclaim this lost heritage. “A lot of these international platforms don’t care about our culture or the legacies of the artists,” he laments. “It’s about money and ego. They only make African music inaccessible to Africans.”

While a handful of local companies (such as South Africa’s SAMP Records) provide vinyl pressing services, these are often smaller-scale operations that outsource their manufacturing to international plants. This makes it difficult and expensive for African artists to release their music on vinyl, which is partly why so many don’t. “I think local music, outside of jazz, doesn’t have a strong vinyl culture,” Jenkins says. “It’s still driven by clubs, DJs, and radio mixes. Amapiano, Gqom and Afro-House, for example, don’t see vinyl releases equal to their influence in the music scene.”

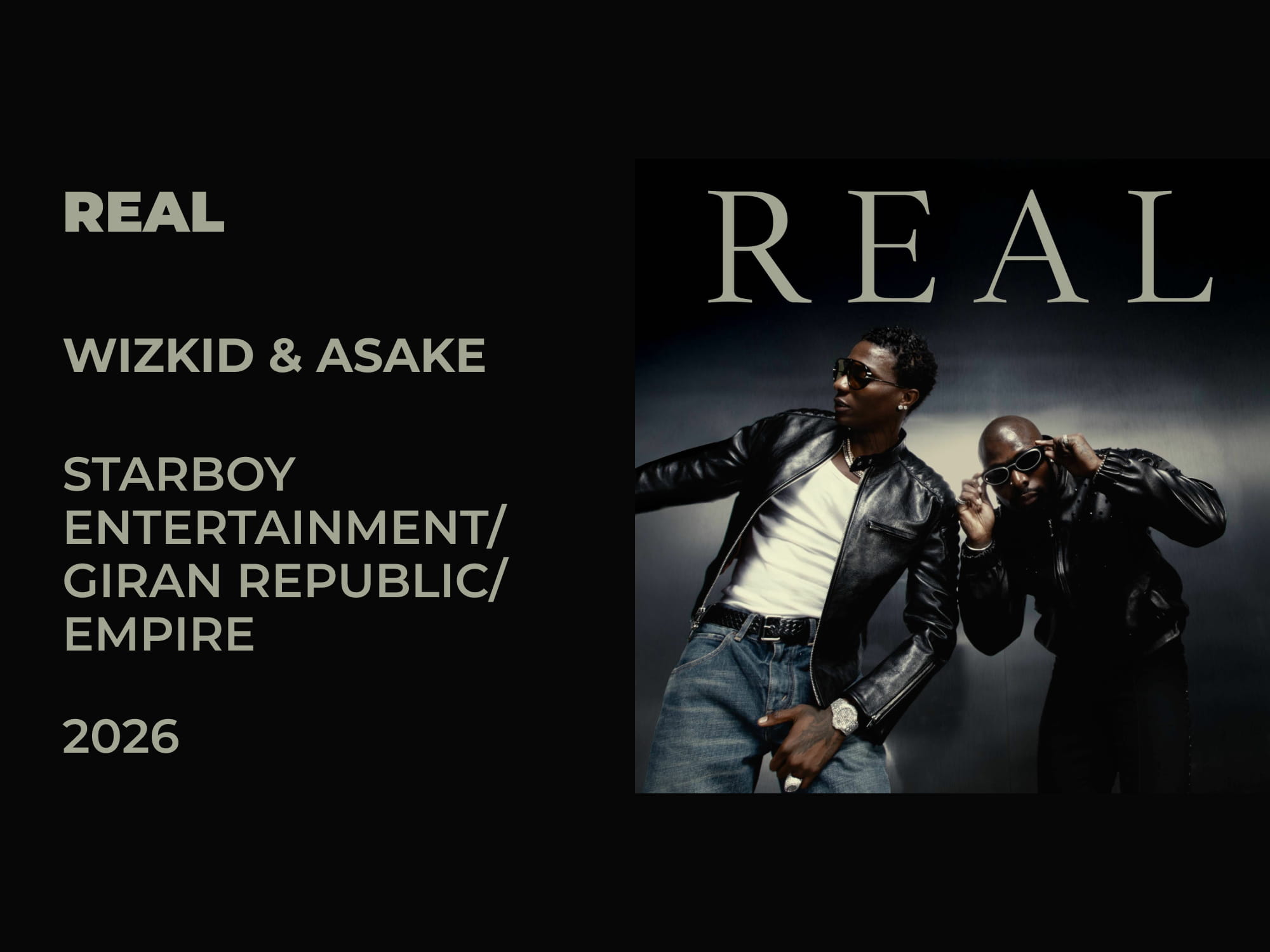

Moreover, the contemporary African music market has a strong digital and singles-driven culture. So even though award-winning artists like Burna Boy, Rema, and Tyla have limited vinyl editions of their albums for sale, the vinyl format (and its growing popularity in the global merch industry) remains relatively untapped.

So how exactly does the African vinyl culture continue to survive?

Tokunbo Culture: A Secondhand Love Story

Translated literally, the Yoruba word “tokunbo” means “returned from overseas”. In the context of calls for the return of Africa’s priceless vinyl heritage, the word takes on a new meaning. However, the term also has significant cultural and economic roots in Nigeria, where informal “tokunbo” markets have long provided accessible and affordable options for several goods, including music. Across the continent, beloved record stores— like the one in Nairobi’s Kenyatta market—serve as sacred sanctuaries for rare and secondhand vinyls.

For many collectors, old vinyl records are a portal into Africa’s vast musical history. Several records from past eras were not reissued in other formats, making the original pressings the only true way to experience that music. This is particularly true for rare Afro-Funk, Highlife, and other classic recordings from the ‘70s and ‘80s, eras often praised for chronicling diverse musical genres and iconic cultural moments. Now that importing new records is a complex logistical process, the true value of pre-loved vinyl lies in the thrill of rediscovering nostalgic musical treasures.

“Nostalgia is one hell of a drug, and vinyl comes prepackaged with that,” Graham affirms. “But I do wonder what will happen when my generation—the last to buy records in record stores en masse—dies out. I’m comforted by the rise of vinyl bars everywhere, from Japan to right here in Accra, where people can pick classic vinyl and listen for themselves.”

Indeed, a pulsing ecosystem of music establishments is springing up across African cities like Dakar, Cairo, and Abidjan, fuelled by enthusiasts and artists keen to celebrate the continent’s musical legacy. In addition to functioning as a record bar and vinyl retail space, the Collector’s Collective hosts vinyl DJ nights, album launches, and showcases for both new and old artists. Online vinyl shops like Play The Crates curate events, access to music-related archives, merch, and quality vinyl. Other South Africa-based companies, such as Mr. Vinyl, specialise in both new and used records, offering cleaning services and equipment repair. Meanwhile, thoughtfully curated experiences like Egwú Vinyl Festival are reintroducing the timeless magic of vinyl to a new generation of Nigerian music lovers.

Africa’s vinyl landscape is uniquely defined by a deep cultural heritage, an absence of local pressing plants, and the rise of a global reissue market. It creates an environment where preservation is key, rather than the mundane pleasure of just enjoying the latest releases. Ours is a vinyl culture rooted in the pre-loved and forgotten gems passed down from generation to generation.

Vinyl As Inheritance

When I ask my friend, a budding music producer named Chidi Okorie, about Africa’s history with vinyl, he insists that I speak to his aunt. Walking into Madam Grace’s home a few days later, the first thing I notice is the old but well-kept gramophone sitting on a wooden side table. She is wearing a vivacious green dress and holding a generous stack of vinyl records in her 72-year-old lap. Like all serious collectors, she’s eager to show off her records, lifting each one gently with a dimpled smile.

She names her favourite artists (Chief Osita Osadebe, Onyeka Onwenu, and Nina Simone), shares her favourite stories, and when asked about the vinyl’s modern resurrection, she replies: “It never died. During the Biafra War, the radio kept us updated on the news, but my records kept me connected to my heart and those around me. This ability to foster connection in a tangible and meaningful way is why vinyl will never truly go out of style.”

Realising that almost an hour has passed without her offering me any refreshments, she calls for her granddaughter, Uju, to bring me a cold drink. As a first-time visitor, declining is simply not an option: hospitality has always been a serious affair in most African cultures. Later, Uju offers to show me her newly purchased record player. Just 20-year-old, she is extremely proud of her baby blue suitcase player.

Critics have had a lot to say about these “new age” turntables, claiming that the renewed interest in them is more about aesthetics than a genuine love for music. Uju disagrees, intelligently pointing out that music and aesthetics often go hand-in-hand, as many old record players and album covers were also eye-catching. “One day, I’ll inherit my grandmom’s vinyl records, and maybe one day my children will inherit them from me,” she says. “My love for music is in my blood. Aesthetics are just a way to express that love.”

Answering The Pressing Questions

There’s been a lot of talk about why vinyl records are making a comeback in the digital age. The more sceptical theorists claim that the vinyl revival is just a passing trend that will fade just as quickly as it started. In response, vinyl enthusiasts have highlighted the Lindy Effect, which states that the longer something has been around, the more value it has and the longer it is likely to last into the future.

Some researchers say the resurgence is simply a matter of ownership. In an age of temporary subscriptions and ephemeral digital footprints, tangible goods provide a sense of permanence. But for many, the vinyl’s appeal is simply in the warmth of its sound. “Vinyl is especially resonant for genres with live instrumentation; think Jazz, Funk, and Soul,” Graham says. “It’s something about the process of pressing those sounds to vinyl. That analogue fuzzy sound that you hear when you touch the needle to the record before the music kicks in. Spotify could never.”

More than just an aural experience, vinyl offers a sensory encounter too. The listener holds the vinyl record in their hands, perhaps pausing to appreciate the album art or read the liner notes; then gently eases the record from its sleeve, placing it on the turntable before carefully dropping the needle on a specific microgroove.

Every step is intentional, and perhaps this, above all else, is what truly makes vinyl so special. Makosholo believes that the ritual of the turntable encourages active listening, creating a connection between the artist and the listener, while Jenkins believes that it invites respect and demands patience. “Unless you want to get up every second, you are more inclined to listen to a track end-to-end,” she says. “So you get the artist’s full intention of the album versus a playlist, where you only experience the curation of an algorithm.”

Can Vinyl Outlive AI?

Artificial intelligence is a topic that has been on everyone’s lips in recent years. In terms of the music industry, AI seemingly offers new tools for production, composition, and personalised discovery, while also presenting undeniable ethical, environmental and economic challenges. But what about its impact on physical forms of music? Jenkins thinks that vinyl has already outlasted AI.“Vinyl has surged as a result of AI,” she notes. “I think vinyl purchases are a bit of an unconscious revolt against consuming music digitally on streaming platforms, and even more digestible forms like the sound clips on social media. I think AI will have a bigger impact, in the short term, on how music is made. I’m more interested in seeing these [AI] tools used by individuals with inclusive politics so we can really assess what the detriments and opportunities will be.”

Madam Grace smirks enigmatically, shaking her head as she responds: “Vinyl records have survived civil wars, cultural genocides, the birth of cassette tapes and CDs, and the continuous threat of piracy. What is AI?”

There’s a popular African proverb that states, “When the music changes, so does the dance.” It’s a reminder to stay flexible in times of great change. Africa’s vinyl journey and its enduring cultural impact offer us countless lessons on the power of adaptability and resilience. Artificial Intelligence might very well bring an end to the world as we know it today. But what has been done cannot be undone, and not even AI can undo vinyl’s legacy.