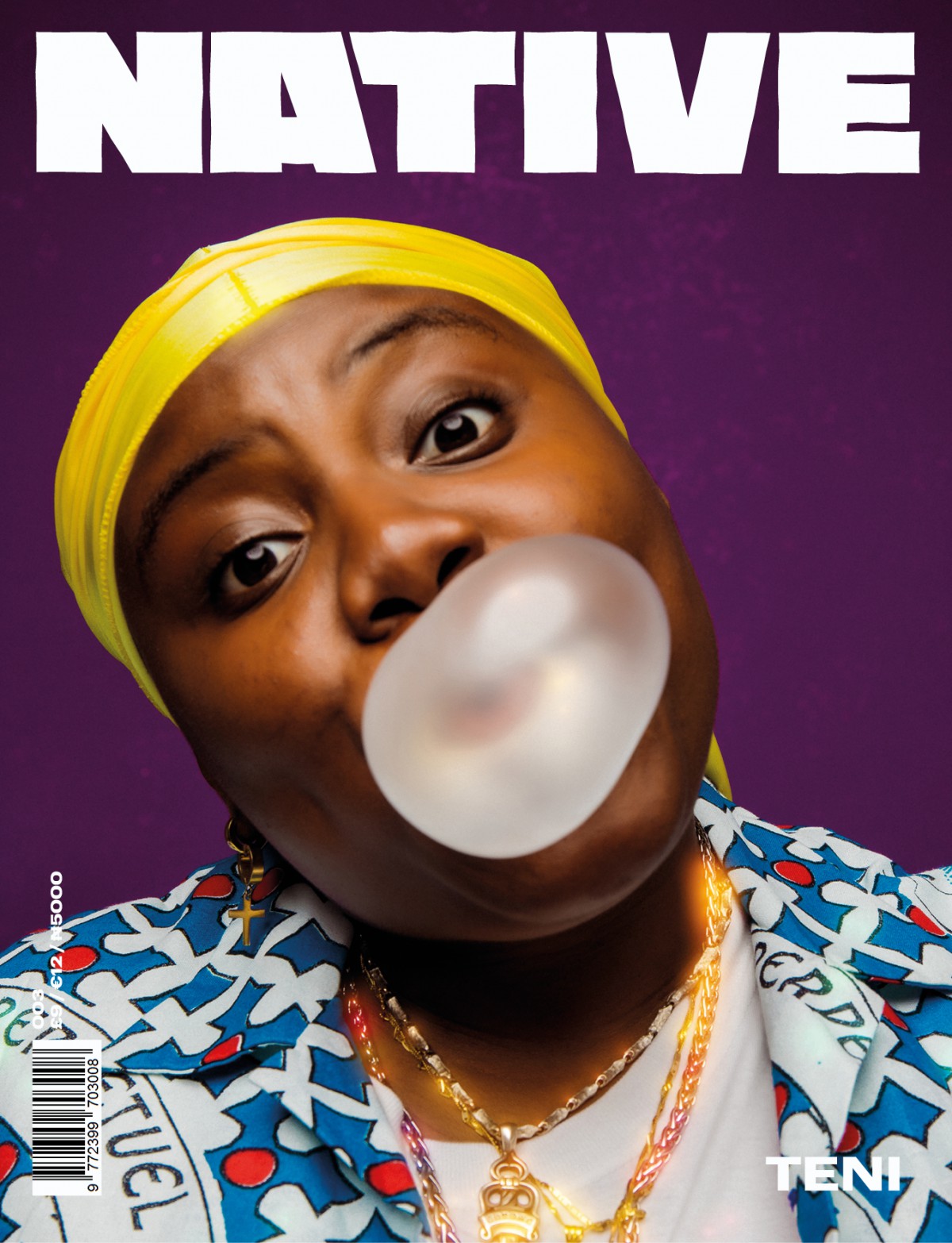

Teni: The Girl Next Door

Teni has broken down every door put in front of her. We speak to her about her songwriting background, how the death of her father inspired her, and nearly going to the WNBA

Teni has broken down every door put in front of her. We speak to her about her songwriting background, how the death of her father inspired her, and nearly going to the WNBA

Words: Joey Akan

Photography: TSE

Styling: VIVENDII

Assistant: Fadekemi Tejuoso

Beside me is the most agitated fan in Lagos. It’s the last Friday of the year, and we’re at Muri Okunola Park for the third edition of NATIVELAND. The most guerrilla of NATIVELANDs yet; tickets only went on sale last weekend, and the infamously-guarded line-up was revealed just 48 hours ago. However, somehow, there are over 6,000 ragers here, ready for the last turn up of the year. We’re well into the night, and Pretty Boy D-O is running through his critically-acclaimed EP. As the crowd chants along to “Chop Elbow”, the young girl next to me is still fidgeting, constantly checking the lock-screen of her phone, I assume to keep track of the time. Her friends assure her that she will be fine, though she seems unconvinced. My curiosity got the best of me. “My curfew is at midnight and I’m travelling tomorrow,” she tells me. “If I don’t see Teni today, I won’t see her till next year”

Love is the dominant sentiment that has catapulted 25-year-old Teniola Apata to success. In a country where actual record sales figures and streams are seldom disclosed, fan love is one of the strongest metrics to measure the impact of an artist. A great indicator of that is found in public spaces like NATIVELAND, where the reaction to the music is raw, unfiltered and instant. Teni has this in abundance. Through five short minutes, she crammed in a performance where the crowd screamed her songs, performed abridged acapella versions with her, and begged for more as she signed out with the the customary, “Thank you, I love you!”

Over the past three Decembers, Lagos has cemented itself as the hub of African pop music, transforming itself into a carnival city of live music. Almost every day from the first week of the month, there are music events and showcases lined up throughout the city. Every corner holds something new; a young upstart with a niche fanbase hosting a an intimate concert, a veteran performer, putting up an event to make retirement a little bit rosier, big corporations celebrating a profitable year with themed luxury bashes, pop stars shutting down streets with traffic from their grand jamboree.

It’s the perfect revellers’ heaven. Only a few elite artists are influential enough to be booked for performances at ‘all’ these events. Teni joined that league in 2018. At the start of the year, she was only a promising upstart with a flair for comedy, who had a decent single, “Fargin”. By December, things had changed drastically. She had become a juggernaut. On most days, she shuffled through concerts, dropping unique performances, and picking up cheques. On one particular night, she pulled off four events in Lagos, and made a 130 km road trip in the dead of the night to Ibadan, where a crowd of over 1000 people were gathered for a concert, waiting for her to show up. She arrived in the early hours and went straight to the stage where her weary fans found new strength to turn up.

***

Teni is having lunch.

We’re at the cover shoot, taking a break between two looks, and Teni is posted up in the corner of the studio, digging into a rice and chicken combo box, sneaking glances at her iPhone between bites. Bags and boxes – her accoutrements for the photoshoot – are her closest companions. To her far right, perched by a clothes rack, are Odunsi The Engine and BOJ – her colleagues turned friends who came to show support; but Teni opts for pre-game solitude.

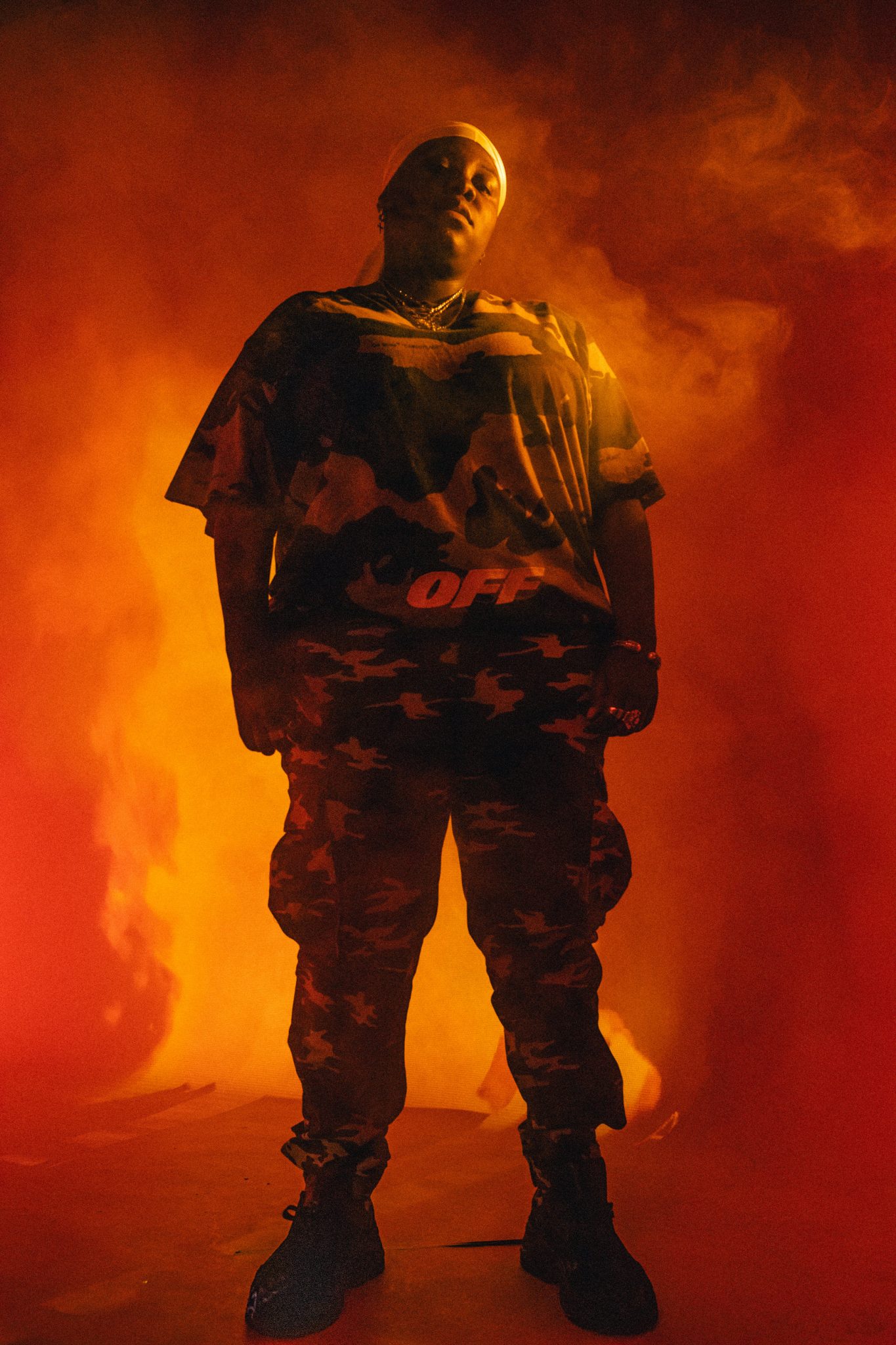

At the other end of the small studio, photographer Thompson Ekong (TSE) pensively paces the set, audibly contemplating which artistic direction to take the shoot that is to come, flanked by Jimmy Vivendii, the stylist for the day. Camera in hand, TSE closes in on the backdrop. Beckoning to two assistants to bring the ladder in for some last minute adjustments, TSE fiddles with the wiring of the projector, distorting the plain backdrop with a visual of a burning flame.

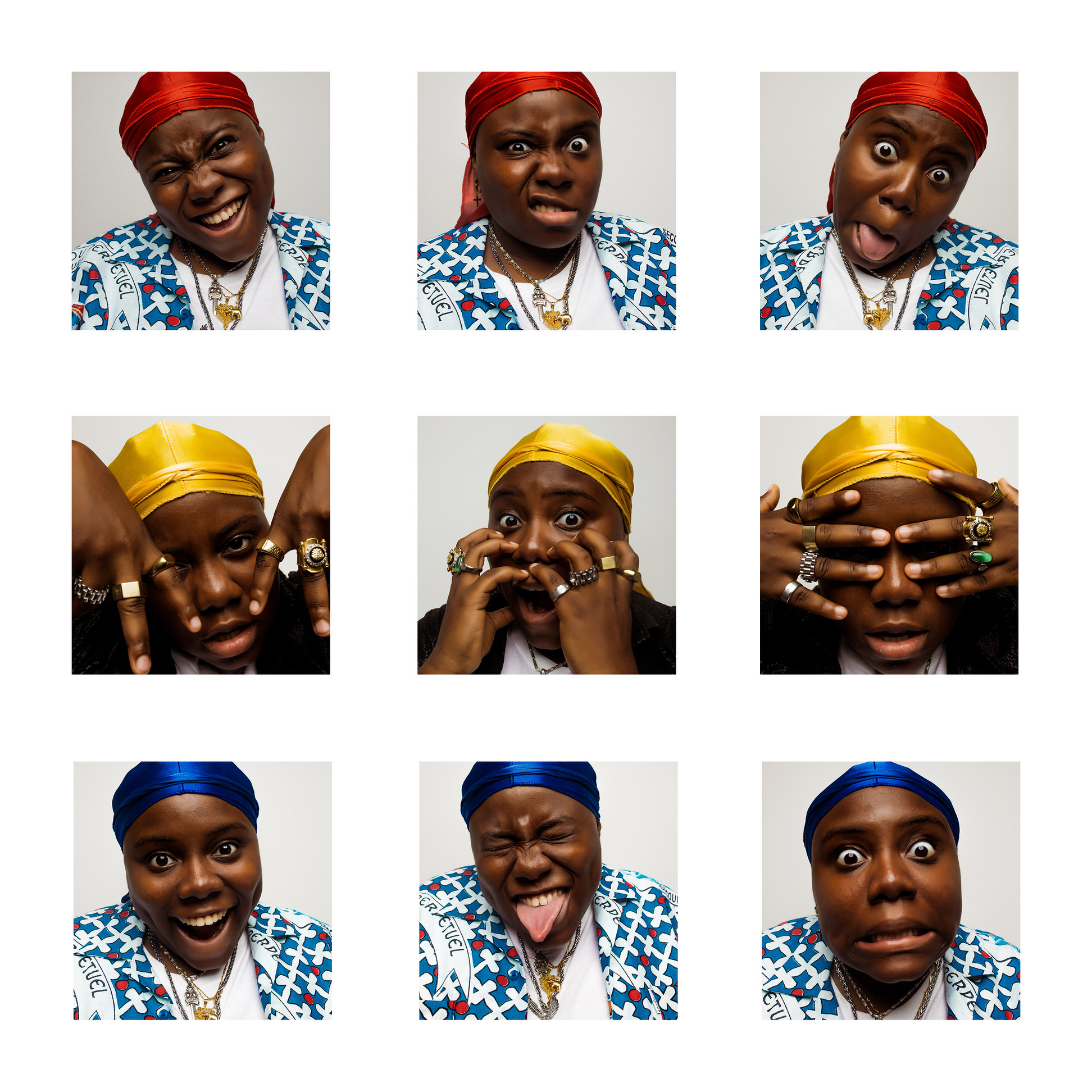

Teni is done. Now changed into her second outfit, she takes centre stage and, just like all the comedic clips that litter her social media, she begins to dominate the room with her humour. First she hugs the flames, calling out the opps who are “blocking her fire.” The room laughs. Next she demands for music to be played, then quickly calls for it to be reduced, accommodating requests for videos of her to be made. Teni looks into the camera, preps herself, and lets the words fly: “My name is Teni, I am going for everything I have ever dreamt of…”

Teni strikes you as someone who has been waiting for this moment her entire life. But, by convention, this moment isn’t meant to be happening. Teni isn’t pop star material, but here we are, a room full of people, everyone playing a role to make her shine the brightest. Gender stereotypes in the music industry stipulates that the quintessential female pop star has to tick a few boxes: ooze “sexiness” – whatever that means and possess palpable sensuality – not sure who’s judging. In many ways she’s the opposite of all the archaic stereotypes, but you wouldn’t know it, when you watch her serenading men and women alike at her live shows.

Teni defies all the rules.

And it is this defiance that scares the industry. It is what prompted Nigerian journalist Osagie Alonge to dismiss Teni out of hand, and straight into a writers’ room, as she does not have “the look”.The argument, that many share but few have publicly aired, is that conformism is the only way to guarantee success. This may have been true of the early-mid 2010s, when all the top names in the industry simply followed a seasonal recipe for hit-making, but with 2018 came the long-awaited confirmation that Nigerian music was at last diversifying. Now, success is no longer dictated by who can best replicate the dominant sound of the moment – talent has never been so defining.

The day that followed Osagz’s moot assessment of Teni’s future, was even more chaotic than the episode itself. Tweeters bashed the tabloid audio-piece, specifically its most notorious voice Osagz, whose gauche comments on Teni’s appearance were joined by an unsolicited exposé of Wizkid’s personal affairs. Wizkid spoke up, threatening Osagz with lawsuits, and Wizkid FC pulled up to the Pulse HQ. Teni, on the other hand, handled the situation with much more composure.

“That is his opinion. How can I judge a man for his opinion? Hey, this man is not going to kill me, he’s just saying what he thinks about you and is that a crime?” Teni challenges me. In truth, Osagz’s words weren’t particularly groundbreaking, he simply made the mistake of loudly asserting a common belief that women can only succeed at one thing, rooted in the assumption that the system hasn’t progressed. It was bothersome, but it didn’t bother Teni. She refuses to let this analysis weigh her down; “Success is the best revenge,” she says with a smile.

“Everybody used to say ‘Teni you have to look like this, you have to do this.’ I needed to prove to a lot of people – not the naysayers, – but the young girls like myself, you can be yourself and win.”

Any millennial who grew up in Nigeria can tell you that the sparse collection of female musicians who have risen to high acclaim all tick boxes prescribed by the androcentric music industry. Artists who veered from the norm have, for the most part, been booted out. These days, rising female acts are encourage to emulate the course of the Number One African Bad Girl, the uncontested female lead for almost a decade now.

But Teni isn’t trying to emulate Tiwa Savage, Teni isn’t trying to emulate anyone. She can’t -the industry has been void of any aspirational female figures to whom Teni could relate. Growing up, there were no plus-size female singers wearing buba and shokoto, styled with Air Max 97s and a bright pink durag, performing explicit songs about sexual affairs. When she was starting out, there were no comedic musicians who fearlessly flaunted the kind of wackiness that is only reserved for close companions, on social media for their fans to join in the cruise. There has never been anyone as uninhibited and unconventional as Teni, but thanks to Teni there definitely will be in the years to come. She has become the role model she was missing.

“I feel very grateful, but I feel like I have so much more to do,” She tells me as we sit to talk. “I feel like a whole generation is depending on me to break certain stereotypes and to open certain doors, especially for the female child, not only in this country, but the African mentality.”

Teni was destined for stardom, destined to inspire the generations that follow her, from as early as two years old. Born in 1993, to Nigerian civil war hero and retired Nigerian Army Brigadier-General, S. O. Apata, Teni was only two years old when her father was assassinated, on January 8, 1995.

“I always watch my father’s funeral,” she tells me very calmy. “It reminds me I won’t be here forever. I need to make sure that every day is productive. I have to follow my dreams and live my life to the fullest by my own terms and in my own way. Not what Joey or my mum wants me to do, but what Teni wants to do. My father was a fearless man; a man that used to chase armed robbers, very brave, a philanthropist. But he’s was laying there, breathless, and I’m like ‘fuck! That’s going to be me one day and I cannot escape this.’ I might as well just face my dreams squarely and say ‘you know what;? Teni is going to do what Teni wants to do regardless.”

Teni’s mortality is always with her. She’s made peace with the truth of life; Nothing is assured and tomorrow is never given. She’s raised it up a few times in our conversation. It’s a daily reminder for her that life is unpredictable, and no one makes it out alive. This knowledge of our limited time on earth, inspires her to live more, do more, sing more, prank her friends more, and spread joy via every channel and platform. All of this is surreal for her. She’s unconventional and rambunctious. Her hair never leaves the comfort of her signature durag. This current good run was a prayer and a distant dream. But sitting in this parking lot, she knows it real. Her dreams came home. She made it.

Through it all, Teni’s father remains her greatest inspiration for her work ethic and the oracle of her success, thanks to his decades-old prophesy into her life and that of her elder sister, Niniola.

“I always ask my sister, ‘how come both of us are in this music industry and doing well?’ I tell her, I just think God is pitying daddy o! I’m not even joking because my father always used to say his children would be superstars. When his friends come around, he has this camcorder, he’ll tell Nini to come and dance for his friends and she would dance and entertain them and ’he used to tell them, ‘she’s going to be a superstar, my children are going to be superstars’” she recalls.

Niniola’s superstar status came first. In 2015, she broke through the Nigerian music scene, with the little-explored genre of House music. Prior to this venture, Niniola was working full-time at their family school business, and guess who encouraged her to quit? Teni. Their family was livid.

“They were all calling me and saying, ‘You’re a bad person, how can you tell her to quit?’ Teni remembers. “It’s because they knew that Nini is good with administration – telling people what to do. But I grew up listening to Nini sing.” So, after a few conversations with her baby sister, Niniola called a family meeting and left the business. Her first single “Soke” became a hit, as has everything after.

Niniola’s success eased the blow for Teni’s parents when she finally decided to join her sister in music. For all the talk about how technology and information has influenced Africans to reconstruct their value systems, in Nigeria, much of the older generation still believe in traditional job security, rather than creative endeavours. This was rampant in the 80s and 90s. Music especially was regarded as the profession of choice for those with no options left. Parents wanted their kids to secure an education and work through corporate jobs. It’s a conventional and stable path, one that almost ensures a regular dignified life. These days, a lot of that has changed, but not without resistance.

“Look at Nini now, Nini paved the way for me because when Nini did it, my parents didn’t believe it was possible. Although they still didn’t want me to do it, they know that I’m a stubborn goat. They always call me a stubborn goat and they knew I was still going to do what I wanted to do.“

Now that “stubborn goat” is well on her way to being The GOAT.

After her whirlwind 2018, Teni is working on her debut project, to capitalise on her current momentum. This is the first night of recording and her to-do list, growing by the minute, is terrifyingly lengthy. On Instagram, one of her favourite utterances is “That’s how star do.” Well, stars also face burnout and pressure from the weight of expectations. She admits that she’s resigned herself to the rigours of her success and that she’s still learning on the job. She still wants to be a writer, and not just a performer, as she reminisces on her big break, penning “Like Dat’ for Davido. “It was a learning curve for me, but writing comes naturally. I will continue to make music for myself and others till I can’t do it anymore.” She doesn’t see writing as restrictive, but rather just another way to express herself. She does however think more can be done to encourage young girls to access varied corridors in the music industry. “Right now other than Nini, I’m listening to an artist called Tems, who is great. But the environment needs to be less toxic, more structure needs to be put in place.” She’s not wrong – and this is a problem not consigned to just Nigeria. In a 2018 USC Anneberg Inclusion Initiative Study, it was found that only 2% of music producers and 3% of engineers across popular music are women. Whilst the Western market makes strides to correct this, such as the Recording Academy’s Taskforce on Diversity and Inclusion, Nigeria, and Africa at large still needs to wake up

After her rookie-of-the-year worthy season, it would be understandable if Teni was feeling a bit of pressure going into the next act. Whilst a handful of phenomenal singles is a good starting point, the crafting of an album is an entirely different beast. But she’s calm.“It’s not a lot of weight, neither is it a lot of pressure because I’m having fun,” she explains. “The typical Teni doesn’t care. I’m living my life as a normal human being. If there’s traffic, I will come down and enter okada and I’ve heard people say ah! You’re a superstar, you’re not supposed to be entering okada’. But if I die, they are not going to write superstar on my grave, right? I’m going to be buried like every other person. So I’m human, and I don’t want to lose my humanity, just to be the same Teni. I will always evolve, but I don’t want to be pressured into a fake life that isn’t for me.”

Teni could have been a WNBA player. She was offered a scholarship to play basketball at college, but her mum told her in no uncertain terms that she was not going to school to do anything other than read her books. Whilst that dream died, Teni still carries the drive of a player going to the draft. That is why none of what is happening now is fazing her. It took her 7 years to finish school, because she spent hours driving from Atlanta to New York, just to record. Such was her determination to make it, against all odds, that she made this sacrifice. She forgave her mum for pushing back again, when she told a young Teni she had a dream that music wasn’t for her (Nigerian mums and dreams, we’ve all been there). But Teni knew. Her mission was ordained. Now her mum gives her business advice on how to save her money and make smart investments.

Everything that stood in Teni’s way has been conquered. Now she is face to face with her dreams, a showdown she’s been preparing for her whole life. Teni is about to conquer those too, and she’s opening up a whole new realm of possibility for the young girls that follow her as she does it.

Joey Akan is an award-winning music journalist based in Lagos, Nigeria. He is a public relations consultant and commentator on African music and pop culture.