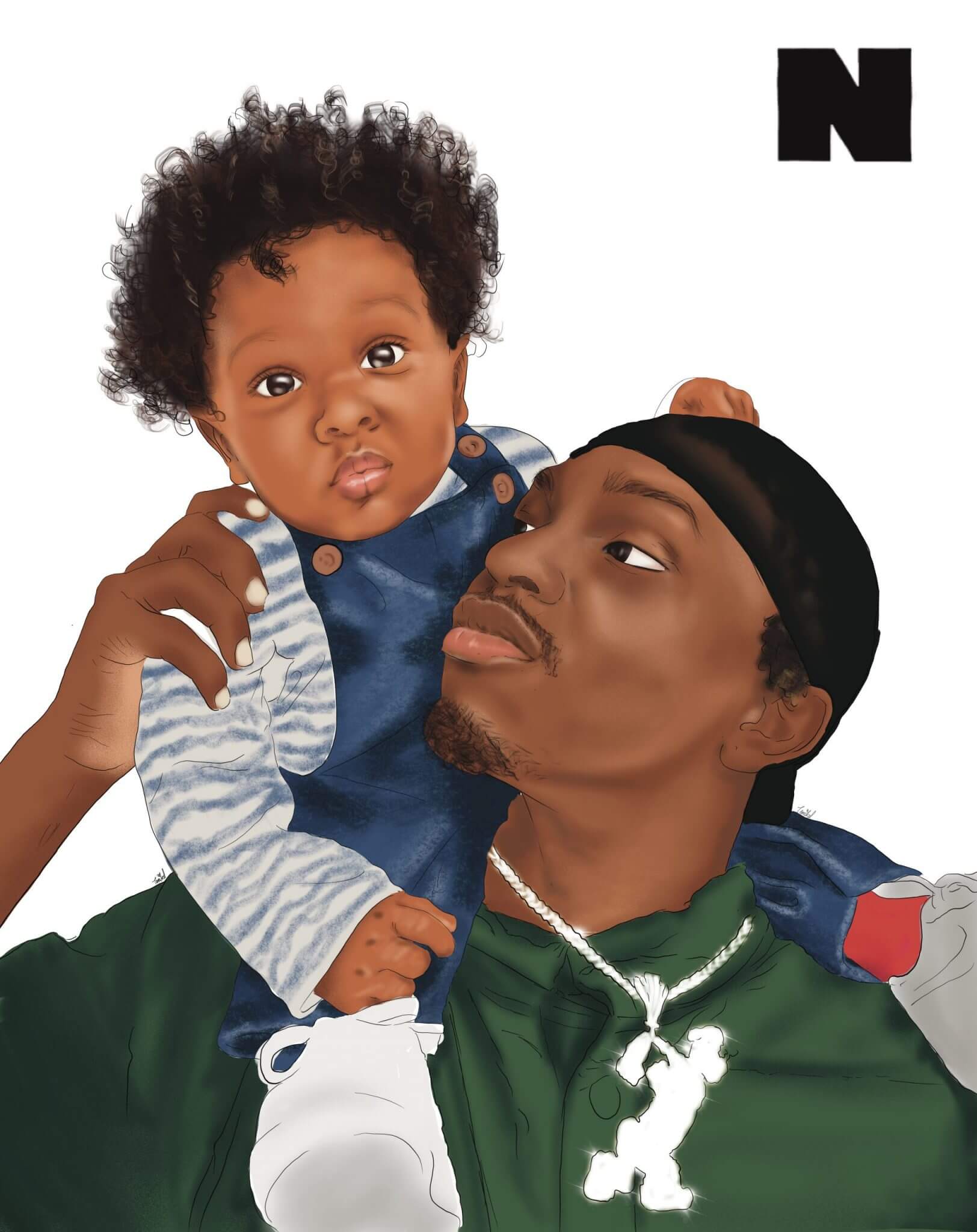

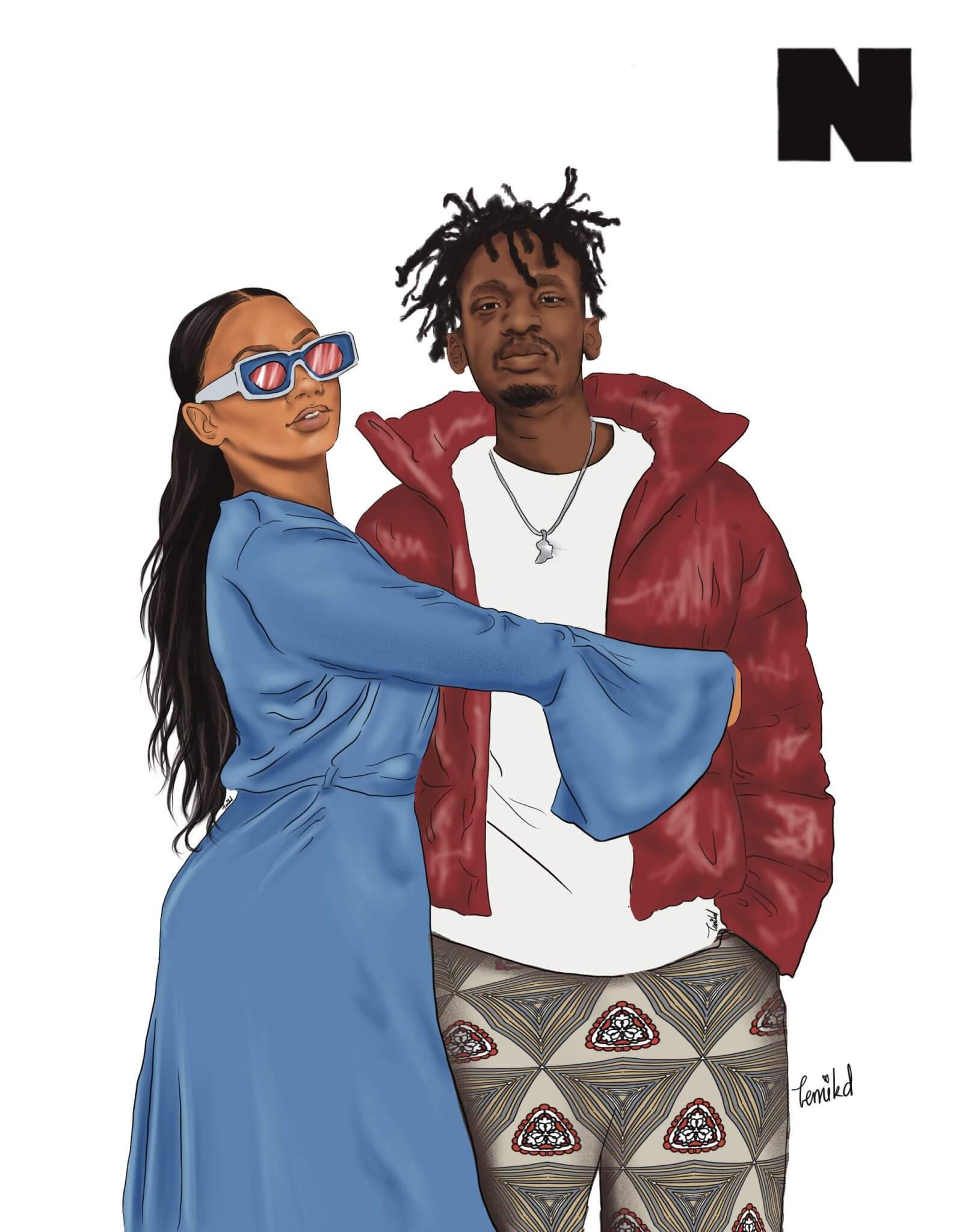

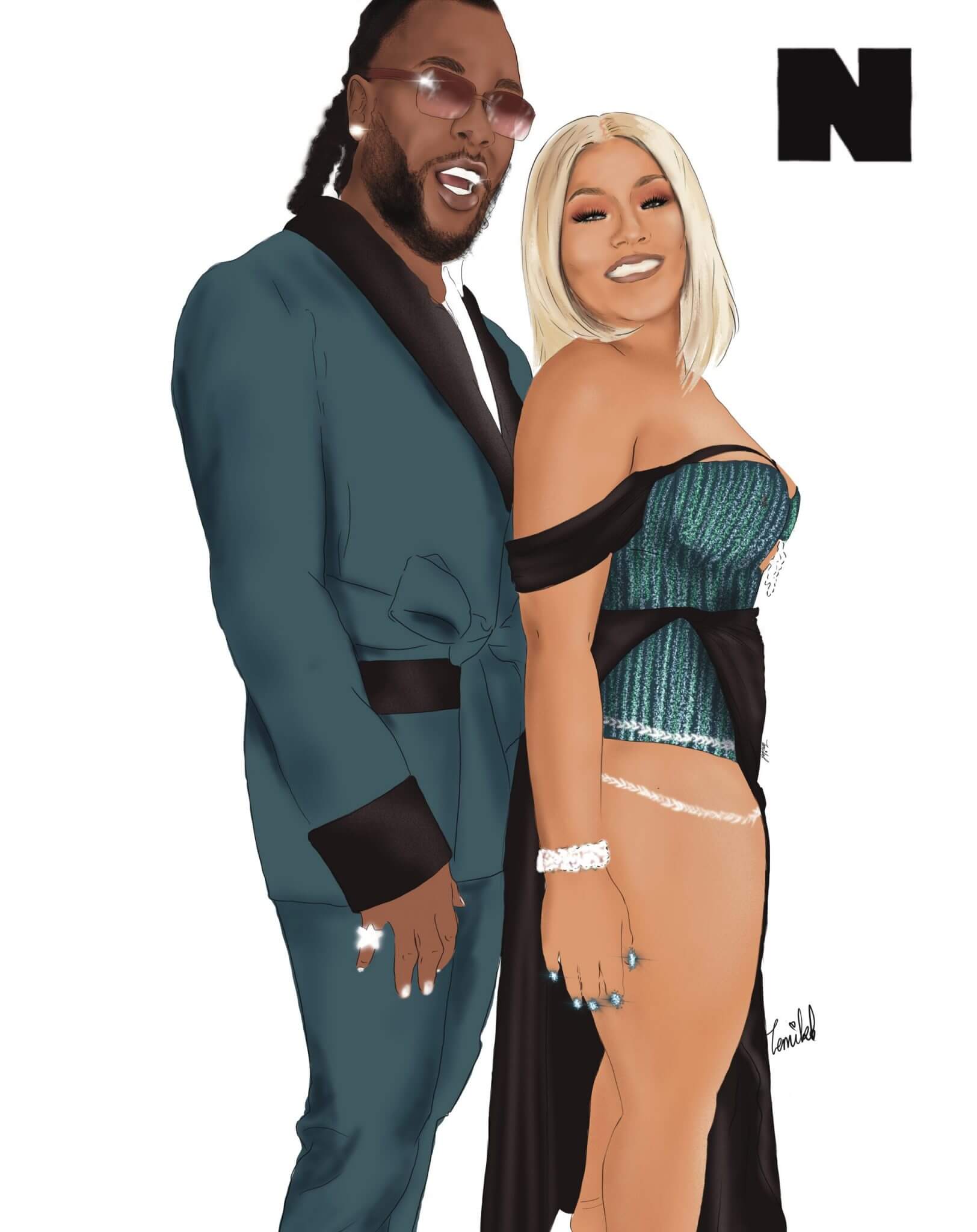

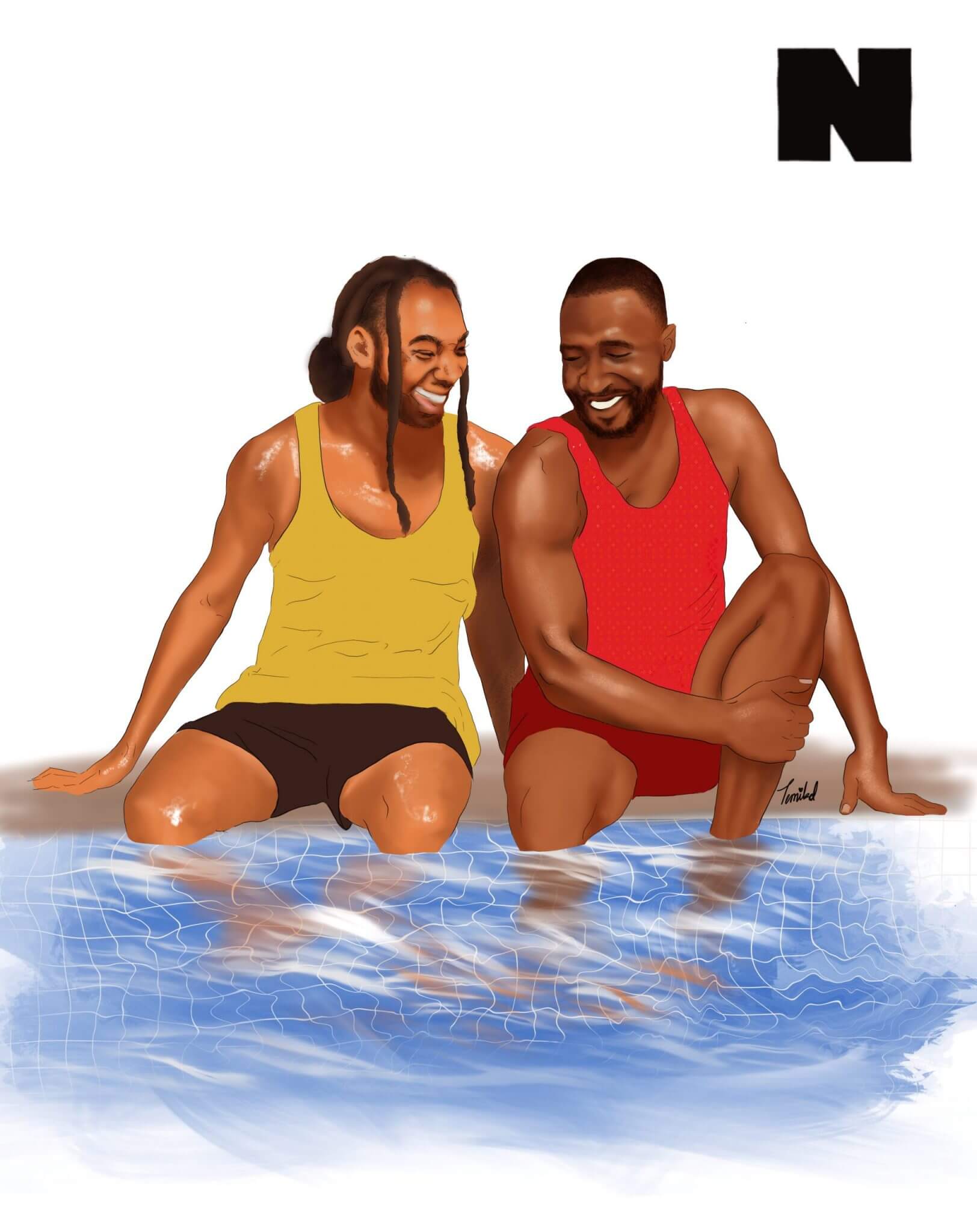

Exploring the contours of Black Love in the UK

"Representation matters. It’s said so often because it’s true,"

"Representation matters. It’s said so often because it’s true,"

In partnership with Bumble UK*

This October, as part of their celebration of Black History Month social media networking site, Bumble are sharing stories and experiences of black love, in a way that the British media has hardly ever seen before. Born and raised in the UK, black love to me meant the bond shared between family; meeting other black students and bonding over our shared experiences of discrimination. Of course, there were times that I did develop a fancy for other black students, but having rarely ever seen representations of happy, stress-free black couples, my default was to remove my blackness from romantic pursuits, even if the apple of my eye was another black child.

Representation matters. As children, our minds are very impressionable. The world is new to us, everything must be learned, and we do so through experiences – our own and those depicted to us by the things that surround us. In an interview with gal-dem as part of their ‘Growing Up With gal-dem‘ podcast series, Tiwa Savage expressed that in teaching her son to say his P&Qs she realised that she didn’t practice the same politeness when speaking to others. What Tiwa Savage was explaining is that if Jam Jam only hears “pass that” and “give me this”, he’s likely to mimic these commands, and unlikely to see the reason or appeal of adding an extra word like “please”, or an extra two in the case of “thank you”. Similarly, when we see only specific expressions of love – during my childhood it was the white-dominated genre of romantic comedies which thrived on female folly, or different variations of the ride or die stereotype when it came to black couples – we learn that this is the way to love, regardless of what our parents tell us. Discussing black love with NATIVE, sex and relationship expert, Oloni tells me “Shows such as ‘My Wife And Kids’, ‘Fresh Prince Of Bel Air’ and ‘All Of Us’ really excelled at showing me what black love is all about. It felt special to see. But that is an issue in itself. Black love shouldn’t be so rare that it amazes you when you see it.“

She went on to say, “when the ‘norm’ is a having functional white relationship on your TV screens, in the magazines and films, you start to associate successful marriages with other races and not your own. Subconsciously you feel that maybe you are less likely to be in a happy long term relationship because you don’t get the same amount of black love represented in the media.” If Jamil struggles to understand why he has to say please and thank you when mummy and her friends and colleagues don’t, then it’s not unimaginable that preachings to black children of healthy romance and self-love fell on deaf ears. Throughout the British media, these narratives were omitted from black people’s stories.

What we learn as children follows us through our formative years and have tangible impacts on our lives as adults – what we don’t learn, when we miss out on authentic representations of blackness, is no different. In addition to the heartwarming videos shared each day over Bumble UK’s socials, the Bumble team also carried out an extensive survey, posing questions to 1,000 respondents between ages 16 and 60, about representation of black love. In this survey, Bumble found that “two thirds (66%) of millennials said the lack of relatable images and stories, about what it is like to date as a British Black person, does negatively impact their mental wellbeing.“

In her Black Girl’s Manifesto For Change, co-written alongside fellow Cambridge graduate, Ore Ogunbiyi, Chelsea Kwakye discusses black love in the context of her Cambridge University experiences, discussing the multiple ways in which romantic inclinations in university have been made a contentious pursuit for black women, and men, “because of how little we see strong representations of black love,” Chelsea writes. On of the first subsections of the ‘Desirability and Relationships’ chapter is ‘Self-Love over Everything’, where Chelsea narrates how throughout her life, she has battled with a sense of shame in her black features, particularly her hair. Being told that her “hair was too big,” Chelsea was also insecure in her constantly changing hairstyles, something that black women are all too familiar with but only just beginning to celebrate.

Chelsea’s fear that people would have too much to say about the fact that her hair was a different length now that it was in braids, speaks to the lack of representation of black women. If non-black people were seeing these regular hair changes – afros, braids and wigs – with the same frequency as we do Collin Firth fall in love, there would be no need for these intrusive uncomfortable comments. More importantly though, if black women were more popularly represented, and our representations also included those of love, of care, of desirability towards us, Chelsea would have felt normal, safe, confident and worthy of love – whatever hairstyle she chose to wear in however quick succession.

Ultimately, if you haven’t seen yourself be loved, if you’re always told that you’re too dark, or your chest is too flat amongst other things beyond your control, it’s hard to even begin to love yourself. So representation of black love, black women being loved, black men being loved, is so important, not only because it has an impact on our love lives, but also because it has an impact on our sense of self-worthiness and love. It’s hard to believe you are something that you’ve generally never been assured of.

In the research conducted by Bumble, respondents were asked to answer how seeing themselves represented in broader British media would make them feel when approaching dating; “included in society“, “empowered and/or confident“, “secure“, “celebrated” and “worthy of love” were the top 5 responses. These responses illustrate that self-love and a strong sense of self is the first most important ingredient in being able to love others, a similar point to the one Saredo made in her quotation above, cited in Taking Up Space.

As illustrated by Taking Up Space and experienced by many black students, dating in university comes with its many challenges, but dating beyond university, where work life might make socialising and meeting new people more difficult, is yet another steep mountain to climb in the never-ending pilgrimage to happily ever after.

As illustrated by Taking Up Space and experienced by many black students, dating in university comes with its many challenges, but dating beyond university, where work life might make socialising and meeting new people more difficult, is yet another steep mountain to climb in the never-ending pilgrimage to happily ever after.

One of the less daunting ways to manoeuvre the dating scene in the UK, as a black women especially, is through dating apps, in particular one like Bumble which empowers women with the choice of making the first move, helping us avoid harassment and giving us the control and confidence that dating spaces have often taken away from us. According to the research carried out by Bumble, “nearly three quarters (74%) of respondents think it is important that dating apps play a role in the way black love is depicted in mainstream online media.” As dating apps have become a mainstay in the world of dating 85% of Bumble respondents asserted that it is the responsibility of dating apps to ensure that they actually present diverse and inclusive stories and are welcoming to varying forms of love, from black love to queer love, to interracial love and the intersection of all of these.

Chelsea reminds us in her chapter that whilst black people are victims of discrimination, within black communities, we often uphold systems of oppression towards the queer community, alienating LGBTQ+ black people within a space we purport to be safe. Over the summer, as Black Lives Matter protests sprung up across the world, so did awareness of the disproportionate violence black trans people face, as news of Riah Milton in Ohio and Dominique Fells’ murders broke. These incidents sparked an All Black Lives Matter movement, which emphasised inclusivity and the need for black people to check their queerphobia. In the ongoing protests in Nigeria, calling for the effectual dissolution of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) and police reform beyond that, chants that “Queer Lives Matter” are being met with bigotry and ignorance, despite the common knowledge that SARS particularly target queer men, or men they believe to be gay. Like women, the queer community are given a lower priority in the fight for justice and equal rights, as heterosexual black men abuse their straight male privilege in these spaces. These dynamics exist within the dating space as well.

Given that masculinity is such a racialised concept, with black men expected to be strong, virile, the epitome of masculinity, for queer men who reject these stereotypes, there are so few representations they see of themselves, talk less of representations of themselves being loved. These strict, traditional gender roles that are violently forced upon black men naturally lead to an incredibly transphobic attitude nurtured within the black community. This bigotry is most often ignored because black people are still victims of discrimination, and as a result, shy away from looking at the oppression they themselves exact. It’s important that in seeking representation for black couples, we don’t fail to include queer black representation, and we are mindful of how our the biases that we were taught as children might still linger within the safe spaces we have created for black people.

Queer and black and a woman, DJ Femo tells me that she is careful of the spaces in which she finds herself, as otherwise, she risks feeling and being alienated in particular spaces within the black community. Lamenting the default homophobia that is driven into the consciousness of every Nigerian child, Femo has found dating in the UK to be a challenge owing to the intersection of her nationality and her sexuality. This has led to her finding her own tribe of like-minded people, rejecting popular heteronormative black spaces in favour of places where she is loved, celebrated and, most importantly, safe – an extremely rare comfort for the black womxn.

However, whilst within our own communities, black people have found spaces in which they feel secure, proud and celebrated, external to the black community is a world of racism and microaggressions that shape our dating experiences even before we’ve secured the date. Every person of colour has a long list in the back of their heads of restaurants, clubs, even general areas to avoid when going on dates or nights out, because the last time you went the staff treated you like a second-class customer because of the colour of your skin. Oloni, who has, of course, witnessed microaggressions – “it’s been hard to deal with because sometimes you feel as though it’s all in your head but when you speak to other black people they too have the same experiences” – raises this issue in the context of first dates, expressing how challenging it can be to “make a good first impression” after having just experienced racism.

“Representation matters. It’s said so often because it’s true,” Oloni goes on. The stereotypical representations of black people that pervade modern media have created a set of expectations of black people that precede us in any context. “We are fed countless pieces of information by the media and the world around us both verbally and visually. It’s impossible for us to not have those images contribute to our opinions and beliefs,” Oloni says, and whilst here, she is referring to what black people take from the mal-representations we see, this statement can also be extrapolated to explain why representation is important is battling racial misconceptions. When they see a black person or group of black people walk through their doors, those establishments that you come to blacklist expect loudness, lack of comprehension, or from my own experience, an inability to afford the higher price points on the menu. They sometimes project racist caricatures picked up from entertainment to new media onto the black people they encounter. In this case, genuine authentic representations of black people, told by black people, through our lens, would go a long way in dismantling the biases white-led media have cultivated for so long.

Naturally, these experiences not only affect the places our dates go, or the way our dates go, they also affect our sense of self-worth and self love. Being able to see yourself more in everyday life, being able to see yourself loved, as a child, a parent, a partner, a friend, will certainly combat the psychological damage of racial microaggressions; seeing this love will remind us that we are indeed worthy. Representation matters for a whole host of reasons, but most importantly, it matters because it empowers.

I take no pleasure in quoting a racist Ghandi here but it is important that we “be the change [we] want to see in the world.” At NATIVE we’re telling the all-important stories of the youth on the African continent from our own perspectives, owning our own narratives – not international press or local outlets helmed by an out-of-touch generation. For sexpert, Oloni the change she wants to see and the change she is, places black women in the forefront of conversations about sexual pleasure, helping “the movement progress and given a safe space for black women to express themselves as sexual beings which in turn makes them more able to communicate their wants and needs to their partners.”

This Black History Month, Bumble is giving the British people the representation that has for far too long been repressed in mainstream media. With over half of their survey respondents noting that they didn’t feel like black love was represented online, just 39% saying they felt represented when they started dating, Bumble are showing us the change we all want to see: Black Love.

View this post on Instagram

Illustrations by Temi Daibo