Credits:

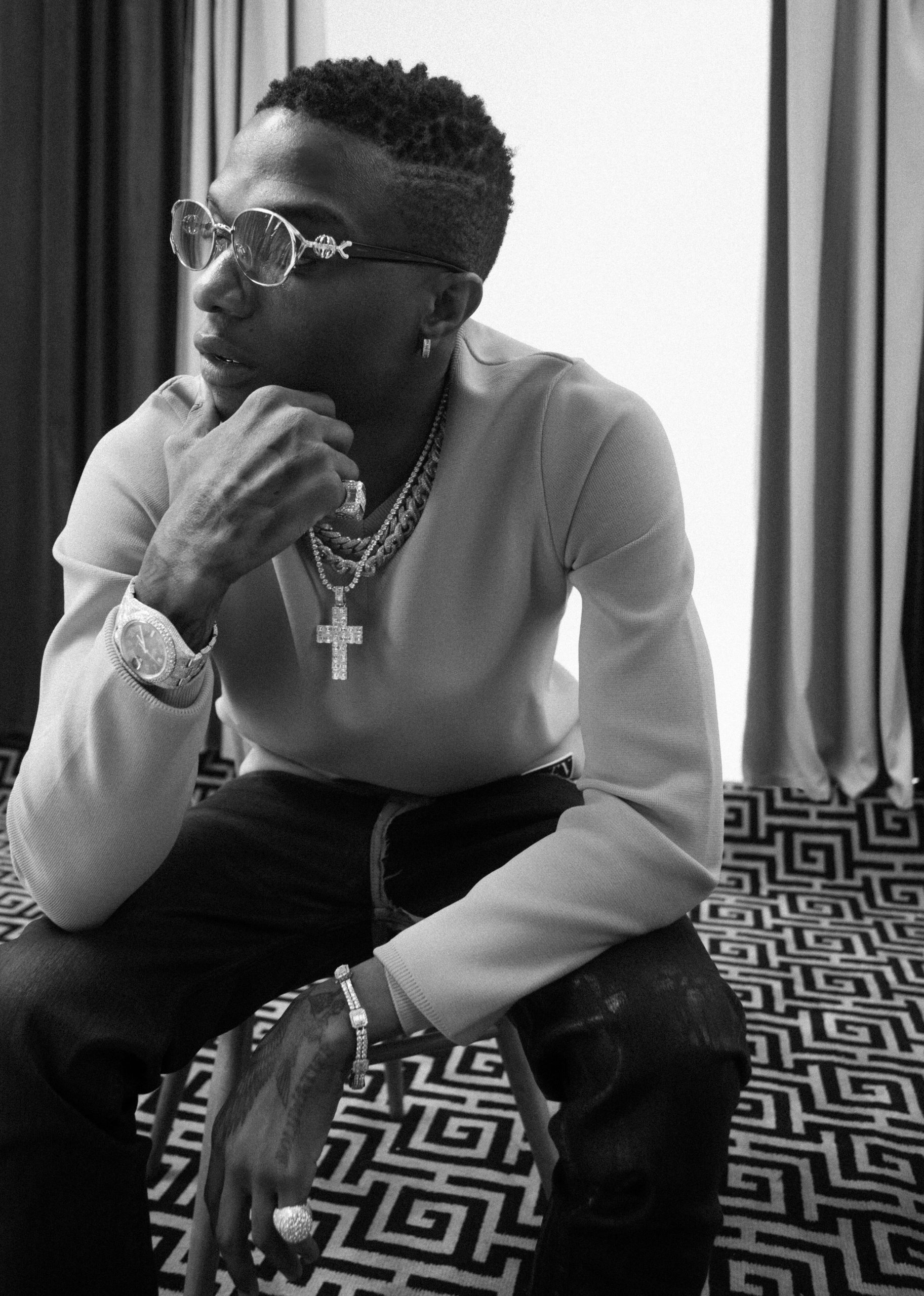

Photographer – Mahaneela Choudhury-Reid (@mahaneela.jpg)

Photo Assistant – Sarah Harry-Issacs (@sarah.harryissacs)

Creative Direction – Daniel Obaweya (nigeriangothic), Mojoyin Durotoye (@moj_bot), A’alia Boyo (@queenoftheyouth) Gaffer – Joe (@lightingbyjoe)

Stylist: TJ for Blac Ribbon

Stylist – KK Obi (@kkobi__)

Stylist assistant – Kennedy Clarke (@yunngflava)

MUA – Fey Adediji (@beautybyfey)

Set design – Jade Adeyemi (@adeyumyum)

Set assist – Sofia Mpandu (@Mustbesofia )

BTS Photo – Tife (@tifeid)

BTS Vid – Barbara (@outtake999)

Wizkid’s emergence at the turn of the decade undoubtedly reinvigorated the cultural esteem of the Nigerian diaspora worldwide. Those of us geographically, and often linguistically, separated from our Naija roots, were able to use his music to reconnect with our Nigerian heritage, but on notes more in-tune with the new found social consciousness of the diasporan youth. This is not a piece about Wizkid’s extensive international commercial success, but the recognition of Wizkid as a renaissance man who injected cultural pride back into the hearts of estranged Nigerian peoples, who could previously only embrace Nigeria vicariously through the stories of their parents.

In the London of the noughties, Nigerians were already known to be studious, charismatic and entertaining, but our cultural recognition had not yet translated musically. Sure, in our homes we may have wheeled up a few legendary highlife tracks, or spent Sundays going through Fela’s sprawling discography, but more often than not, these remained private indulgences. This secrecy was not due to shame or embarrassment of our contemporary music, but our diasporan preoccupation with grasping our Black Britishness. Second generation Black African youths across the UK were figuring out how to legitimise their identity in a society where assimilation appeared to be an unstoppable force. Lyrically and sonically, we were relating more with the narratives pushed in Stateside Hip-Hop and Rap or, more locally, UK Grime. Across the street, it was clear to see how the dominance and popularity of genres like Bashment and Dancehall amongst inner city black youths, served a testament to the social currency attached to being Jamaican in the U.K. at the time. The slang, style and culture of the Caribbean was exported into London and naturally underpinned its black social scene – with the raucous Notting Hill Carnival at the end of summer, serving as the annual celebration of this. Gradually, African pride was in third place, as the more securely established Carribean-infused genres influenced Black British culture.

But, in what seems like the perfect alignment of a maturing UK culture scene, the coming of age of an expanding and self-assured diaspora, and an exogenous curiosity in the development of the motherland, Wizkid successfully materialised this equilibrium into becoming a household name. Hit songs such as “Don’t Dull” and “Pakurumo” offered British Nigerians an opportunity to truly “party like ‘99” in a modern, yet nostalgic way. Wizkid widened the appeal of African feel-good music in the UK in a way that the legends that came immediately before him, were frankly unable to. Don’t get me wrong, songs such as Styl Plus’ “Olufumni”, Olu Maintain’s “Yahooze”, and Mo’ Hits’ “Gbono Feli Feli” soundtracked memorable collective moments, but that delight was restricted to hall parties, living rooms and personal playlists. With their long, serenading intros, and bridges that made you close your eyes and clutch your chest, these classics made us feel, but they still felt like sounds for a previous generation. They kept Nigeria a possession for emigrants now getting into their 40s, rather than an intergenerational refuge for us all. Wizkid’s discography helped to inject a youthfulness into the Nigerian culture that connected us over here, there and anywhere we resided. Wizkid represents the juncture at which Nigerian music was modernised beyond music, but into a cultural movement that facilitated subsequent transatlantic solidarity.

Wizkid made Yoruba and Pidgin sound palpably fun in his music, using catchy phrases that had Western equivalents we could relate to. As he so often did, he would reel off names, shouting-out friends and famous figures in his sweet melodies, it instantaneously put a smile on the faces of those of us who had had to endure oppressive pronunciations of our beautiful names. We were truly proud of the boy who was proud of where he came from, which in turn intensified our own Nigerian identity. We didn’t want to just repeat his words, but become fluent in the language of our parents. The more successful Wizkid became, the greater the mainstream appetite for African music and the more our diasporan cultural pride grew. He came across as cool, humble and promising with a winning streak that assured us that this movement was more than a moment. It’s like he knew the importance of intra-African collaboration and paid homage to existing and emerging talents across the continent. His pan-African approach ensured that the rise of contemporary African music was inclusive and the united British diasporic West and West Africans in particular.

Of course Wizkid did not rise alone, but in the company of many other very talented artists who together certified Afrobeats as a genre that could compete with western hip-hop, rap and dancehall. The Ghanaian-borne azonto craze arrived in the UK at a similar time Wizkid was making his own debut which would help shed the inherited pseudo-tensions between diasporic Nigerians and Ghanaians in the UK. Wizkid, just like Afrobeats, was now fundamentally an African export rather than exclusively Nigerian. Yet, still, Wizkid’s prominence bestowed upon British Nigerians confirmation that any further suppression of our Nigerian pride as necessary to accommodate our Britishness was no longer necessary. Yes, we were British, European or American but there was room for our Nigerianess, too.

For many years young British Nigerians like myself wondered whether Nigerian entertainment had already enjoyed its golden age. Surely our global significance would not be limited to the likes of Fela, Sade or the stars of Nollywood, nor were hall parties and traditional ceremonies the only places our music belonged. But thankfully the stars aligned for Wizkid as he not only stepped up to the plate but went above and beyond. He kept his eye on his fan-bases across the world and knew the importance of the diaspora in pushing his music. At the same time he kept making hits that felt like he never left Nigerian soil and quickly became an artist loved by parents and children alike. There were simply too many of us enjoying Wizkid for Afrobeats to play second fiddle to other genres in the house parties, underground gatherings and eventually the clubs. From one or two African songs reserved for the end of the night to whole raves dedicated to appreciating the sounds of Africa, us diasporans will never forget the role Wizkid played in this phenomena.

I was about sixteen years old when my own father showed me a brightly coloured CD sleeve titled Superstar. He had just come back from a visit to Nigeria and was eager to play me what he considered to be the talk of the Lagosian streets. I trusted my father’s taste in music, as he had been so right about projects by Da Grin, P-Square and 9ice before. He played me the whole album whilst we took a pointless journey around North London, trying to convince me this was a masterpiece. But I needed no convincing. Little did he know he had already placed in me a deep sense of Nigerian pride growing up. One I couldn’t quite articulate, but sat in between his rants about Nigerian political affairs and the sweet taste of egusi soup. But this Wizkid project hit differently. He unleashed a warmth inside of me that I did not want to pass. Adrenaline took over my body at the prospect of having this album stored on my iPhone 3GS. If I was forced to be separated from buzz amongst my peers in Nigeria, then at least I could attempt to forge a closeness with the help of iTunes. After many nights playing this same album on loop, I was eventually able to passionately recite his lyrics to other African kids from my estate. They in turn would exchange the names of the native singers emerging in their home countries, whilst equally excited about the new frontier Wizkid was straddling.

I’d go to house parties and see my friends connecting their phones to the sound systems, so that we could all sing along to “No Lele” like the national anthem, albeit thousands of miles from said nation. It felt spiritual seeing second generation Nigerians demanding to hear “Nigerian music” in the absence of their parents and in the presence of non-Nigerians. It was as if Wizkid had been appointed as the Nigerian ambassador to the UK or head of Diasporan cultural affairs, the way his name garnered respect among Nigerians and non-Nigerians alike. Again, not to say there weren’t any Nigerian artists we could shake a leg to but Wizkid embodied the wider social consciousness of the Nigerian diaspora. He comfortably led the scene in London, making the prospect of an internationally-renowned career as an African artist in the UK possible. He kept delivering, inspiring and strengthening Nigeria’s reputation worldwide.

By the time I got to university in 2013 the evolution of my Black Britishness identity had been altered forever. I was no longer just a Brit with Nigerian roots, but a Nigerian residing in Britain. Studying modules in African economic history and residing as President of my university’s African and Caribbean society was a surreal moment in time for me. I was reading about imperial atrocities inflicted on my people during the day, and by night I was curating Afrobeats playlists for society members to dance to at the after-parties. I had to reconcile the past with the possibilities of the present. Culture, but specifically music, was becoming the liberating force that academics had erroneously predicted politics and economics would be for the Nigerian diaspora. The cultural cohesion between Nigerian nationals and the diaspora removed the geographic barriers between people who longed to be the authors of their own story denied to them by lands. Just like this revolution, Wizkid’s significance transcended borders. For many of us at the time our new found pride also increased the desire to visit, work or live in Nigeria. Nigeria was no longer the land we had to visit under duress, either as punishment or to attend an estranged family function. Instead, it became the country that we wanted to explore, serve and progress. We wanted to be amongst the people that inspired the music, so we too could update the tales of our parents and sing the songs with greater meaning. The esteem of Nigerians all over the world naturally increased interest in our food, fashion and literature. It was as if the world had just discovered Nigeria and we had to quickly establish ourselves as its international vanguards.

Nearly ten years since my Dad came to the house with that brightly-coloured CD sleeve; since that destination-less drive in North London; since the subsequent nights that summer where I would fall asleep to “Love My Baby”, who would have thought I’d be standing on a beach in Portugal, amongst a crowd of thousands of equally enthusiastic Afro-Pop fans, singing those very words like it was the first time. What were once private indulgences, are now supranational treasures. As we continue to expect great things from Wizkid, and witness his artistic evolution and success, I hope we never take for granted this era we are living in now. Although it seems as though the Sounds from Nigeria and the influence of Nigerian culture are ubiquitous, lest we forget there was once a time we were ridiculed for being African. For being Nigerian. The British-Nigerian teenagers today grew up seeing Wizkid and his great peers and proteges headlining and selling out festivals all over the country. You can hardly blame them for struggling to truly understand the symbolism of Wizkid’s journey and the cultural chains he has broken for all of us here. But nearly ten years since this Nigerian girl from Camden Town was introduced by her first-generation father, to the boy from Ojuelegba, I will never forget, and I will forever be thankful to Wizkid for bringing me back home.