Credits:

Editor-In-Chief: Seni Saraki

Managing Editor: Tami Makinde

Writers: Dennis Ade-Peter and Wale Oloworekende

Creative Assistant: Ada Nwakor

Editorial Assistant: Wonu Osikoya

Editorial Interns: Mooreoluwa Wright, Judith Icha, Nwanneamaka Igwe and Bolakale Ogboye

Photography: Demola Mako and Ifebusola Oluwafunmilayo

Cover design: Adeshina Ladipo and AbdulRahman Dawodu

Collage design: Chukwuka Nwobi

Lighting: Victor Gideon

Production Manager: Adedamola Adetunji

Set Assistant: Nwanneamaka Igwe and Judith Icha

Styling: Demola Mako

Designers: WafflesNCream, Poserboy, Rë Lagos, David Blackmoore, and Gëto World

BTS Video: Dante Karibi-Whyte and Ayo Odunsi

Location: Fluid Locations

Lagos, Nigeria – It looks like the paint is barely dry inside Bella Shmurda’s new luxury apartment in Ikota, GRA. Welcomed by an unmissable custom Dagbana Republik (Shmurda’s imprint label) mural in his living room, Bella’s new digs are a far cry – approximately 50 kilometres – from Okokomaiko, the far less glamorous part of town where he stomped for the better parts of 24 years. It’s a sunny day in Lagos and we’re on set to shoot one of the most prominent voices of the streets in the last year. There’s still a vivid fogginess to his movement as he saunters down the stairs and languidly struts around the open space in front of his house. About a dozen other people are in the vicinity, all attending to different aspects of the cover shoot, but no one bothers Bella except they’re tersely answering a question or seeing to a request.

Then the switch happens after some minutes: someone a bit more attentive to Bella’s mood asks if he’s ready, he nods and immediately enters star mode: exuding confidence with every strut. As camera shutters begin to click and lenses start to hover, Bella shuffles between poses and hand signs, rolling his shoulders and springing on his knees ever so slightly that WAFFLESNCREAM’s oversized Ankara gear wobbles and bounces over his diminutive frame. Intrigued by the change in his disposition, and amidst the laughs he’s already eliciting with humorous quips, someone else in the crowd manages to ask how he’s adapted to being the centre of attraction. “It can be stressful,” he says absentmindedly before throwing his hands up as if to add, “but it’s part of the gig.”

The journey to becoming one of Afropop’s emergent superstars dates back further than this current moment, however it took definitive form with the release and acceptance of his breakout single, “Vision 2020.” A true hustler’s anthem, the singer, born Akinbiyi Abiola Ahmed portrayed the bitter reality of making it in the hood, where opportunities are self-created and rewards are often born out of great risks. Bella’s willingness to show emotion and write autobiographical lyrics quickly spread like wildfire, connecting listeners navigating a similar reality.

Initially surfacing in late 2018, the entrancing appeal of the song lay in its evocative details, with Bella recounting his desperate motivations, and the illicit lengths he allegedly went to in order to manifest better economic conditions. By the time Nigerian superstar, Olamide jumped on the song’s remix, Bella Shmurda had already been set on a path to stardom. “Shout-out to Poco Lee, he was like, ‘yo, let’s do a video,’” Bella says, narrating how his breakout moment came about. “Vision 2020” was one of those my tracks I never really took serious, so we just made the video, posted it on social media, and Baddo [as Olamide is affectionately referred to] saw it—you know, real recognise real, it’s in the blood, it’s in the feeling.” The way the singer sees it, hitting it off with Olamide is partly a function of their shared realities, given that both artists experienced economic lack while growing up and are now still holding a mirror to the realities that shaped them through searing music.

This year marks a decade since Olamide’s debut album, ‘Rapsodi’, a cult classic which effectively paved the way for artists making music soaked in street realism. Anointing himself back then as the “Voice of the Streets,” the Bariga-born maverick largely spent his blistering 2010s making music for the hood, paying homage to the people, places and experiences that shaped him. Even as the rapper crossed over to the affluent side of town, he never strayed from his singular focus, using his increased visibility to uplift their realities.

These days, his music has mellowed out, an apt progression to reflect his maturity and the life of comfort. However, the reality that forged him still finds its way into the music in sharp bits. “[Olamide] has made it to some extent but he’s still connecting,” Bella Shmurda says while swivelling lightly on a chair in his home studio. “We are both angry face and hungry belle,” he adds, crystallising what made the song captivating to many who heard it beyond his initial set of listeners.

“It’s a good thing when you pass through the process,” he tells The NATIVE. “The process is where I come from, the time, the people, the angry faces, the hungry bellies, these things are the major impact in my music. I’m part of those angry faces, and the only way I can speak for all of us is just to express, and that’s what I’m doing with my music.”

******

Bella’s music, laced with doses of visceral reality and hood specific lingo, is part of a rising tide in Nigeria music. Over the last decade, music from Nigeria’s less affluent areas has risen in popularity thanks to the acceptance of, first, indigenous hip-hop and, then, pop music inspired by street parlance. At the turn of the 2000s, Nigeria was standing at a crossroad, on the verge of returning to democratic rule after years of military dictatorships and coups. This period marked a creative renaissance for the Nigerian music industry rising from the ashes after years of rut. Festac Town, a residential area in the southern part of Lagos, became the hub of this rebirth. First established in 1976, as Nigeria hosted a pan-African arts festival that drew high-profile attendees from across the continent and in the diaspora, Festac already held a significant historical value, playing a key role in the foundational years of contemporary Nigerian pop music.

“Festac was like a Mecca,” says respected culture critic and commentator Osagie Alonge. “Everybody that was doing music then was in Festac. Whether it was Baba Dee or his younger brother Sound Sultan or even 2Face.” While many of these artists created in proximity to each other, they all made music that reflected their individual realities. For artists like Blackface, after years being part of a boy band that commingled R&B, rap and schmaltzy pop melodies, his immediate stint as a solo artist in the early to mid ‘00s was rooted in an unyielding portrayal of the conditions being experienced by Nigeria’s underclass, exemplified by his classic debut album, ‘Ghetto Child’.

Within the same era, just a few kilometers away in Ajegunle, a crop of artists were repurposing reggae music with Nigerian cadences and tinctures for a style they called galala. Led by Daddy Showkey, acts such as Baba Fryo, Danfo Drivers, and African China took over the music landscape with a deluge of hyper-vivid songs inspired by the realities of living in one of Nigeria’s poorest ghettos. However, primarily operating without access to higher-end infrastructures stemmed their surge. The music they made was antithetical to the slicker sounds pushed by the Pop starKennis Music-signed 2Face Idibia and twin duo, P Square, meaning that they were not as publicly embraced as many influential patrons. Today, street pop is permeating even the mainstream.

“Street music is the sound of the moment,”

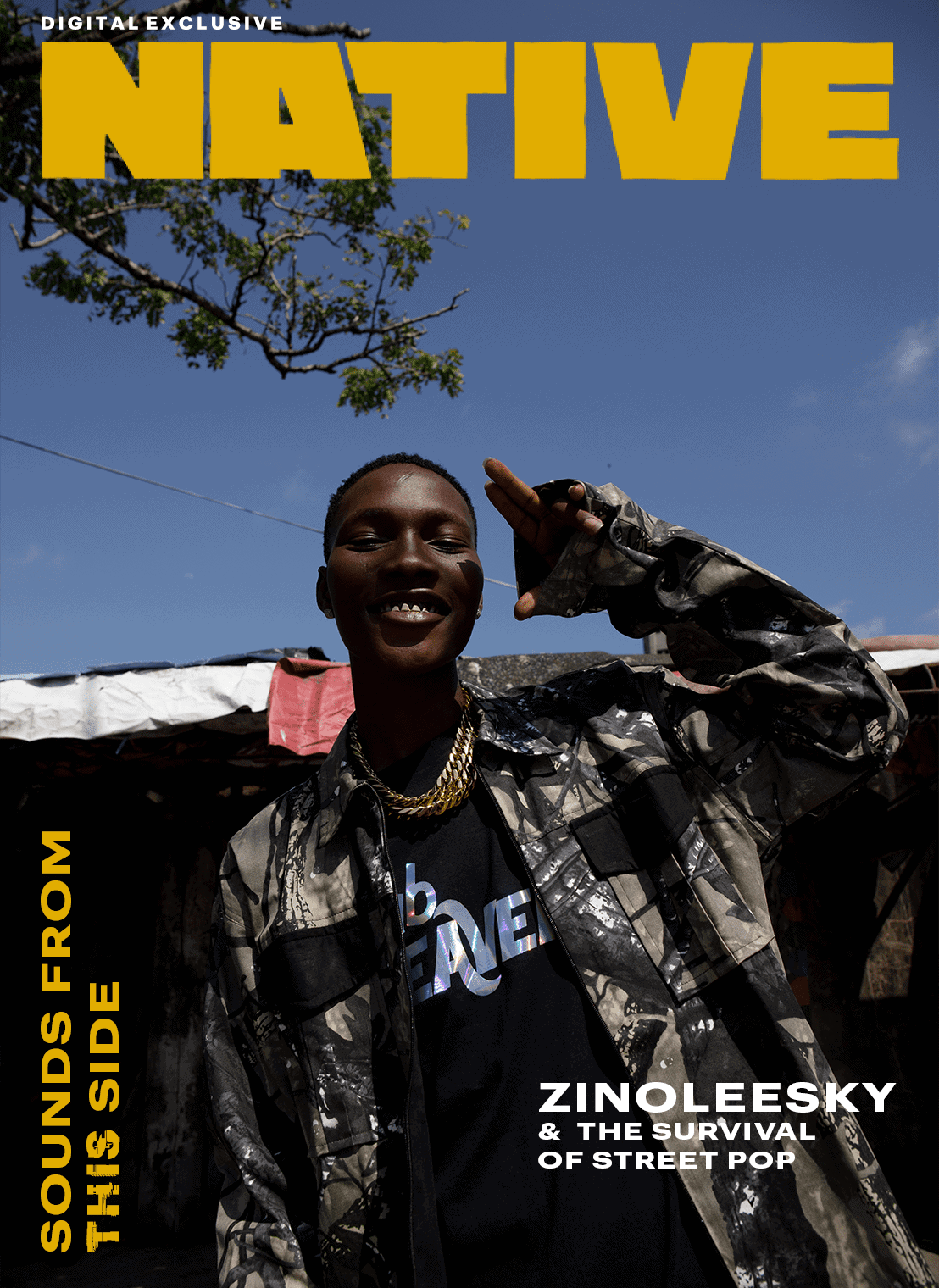

“Street music is the sound of the moment,” Zinoleesky calmly says on a clear Monday morning in August. “That’s what everyone wants to listen to, we’ve really come a long way.” Leaning against his red and black Chevy at a just concluded shoot in Ikoyi, the singer is only two weeks out from the release of “Naira Marley,” a pseudo-tribute to his label boss, Naira Marley, that is also a reflection on life growing up in Agege, a lively border town in the north of Lagos. “I wanted to inspire my people,” he says about the song. “I want them to know that they can achieve whatever they want.”

Originally scheduled to hold in Agege, a security incident in that part of town means that we have to set up the shoot in the more serene and upper scale environs of Ikoyi. If Zinoleesky is bothered about the change, he doesn’t show it, engaging with his friends with a casual nonchalance as the creative crew set up in the dusty car park around him. That level-headed clarity has perhaps played a key part in grounding the rising 25-year-old talent, born Oniyide Azeez Oluwashina, who has enjoyed a rapid change in fortune over the last 24 months.

In 2018, just as Afropop was beginning to steadily incline on a global scale and rubbing shoulders with other sounds and cultures, a similar revolution was taking place here in the burbs of Lagos. While a string of breezy Afropop hits ushered in the clarion call: Africa to the world on the mainstream, and a new class of alternative genre-defying artists were growing, a group of young rappers were also on the cusp of a similar explosion. Zinoleesky was one of those ambitious rappers, waxing poet over beats to soundtrack the life he lived and the one he wanted. A popular series included a young Zino rapping raucously along with his peers to the instrumentals of Chinko Ekun’s runway hit, “Able God.” Rhyming in a mix of pidgin and Yoruba, the young artists had no idea that they were already ushering in the next frontier of street pop’s latest rapprochement.

“At that time, we were still living in Agege and we just wanted to get heard,” he explains. “Lil Frosh loved freestyling, so we came up with the idea of recording videos in the hood, with our people, and putting them online. It was just us having fun and expressing ourselves but people liked it and it became a big deal.” The videos offered listeners a portal into the inspirations and perspectives of young adults trapped in hoods that would go on to have an eruptive and consolidatory effect on street pop.

Piggybacking off these viral successes, at the top of 2020, Zino signed a deal with Marlian Music, the imprint founded by Naira Marley. “When Naira Marley called me, I knew he was giving me an opportunity and I had to take it with both hands,” Zino says. “It’s also been really easy adapting with Naira because he’s a great person that shows you mad love and treats you like family.” Both singers had areas of commonality, with Naira Marley also spending parts of his life in Agege and defining 2019’s zeitgeist with his lurid take on street pop.

Naira Marley first connected with mainstream Nigerian audiences on 2018’s inescapable “IssaGoal,” an enduring visage of the switch of sonic preferences towards street pop. Already a pioneer in the UK Afro-swing scene, his pivot to afropop came by way of the Olamide and Lil Kesh-featuring track that became an unofficial soundtrack to Nigeria’s 2018 World Cup campaign. Subsequent releases like “Japa” and a standout showing on Rexxie’s “Foti Foyin” placed him in the lineage of ascendant street pop musicians.

In 2019, a brush with the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) threatened to halt Marley’ ascent, as the infamous anti-graft agency turned their attention to him, weaponising public sentiment against aspects of street pop.

Some argued that the sound’s proximity to endangered communities means that they were complicit in fraud glorification. Levi Adewumi, a Lagos-based entertainment consultant thinks it is the wrong way to look at the situation. “Artists are heavily influenced by their communities,” he argues. “With street pop acts, they see certain things as normal and, sometimes, they feel like these acts are things that are widely accepted and it flows into their music.” Marley isn’t alone in drawing the ire of authorities and from sections of the public for speaking their truths, as Bella Shmurda and Zlatan too learnt, following the backlash to their infectious hit single “Cash App”.

The authorities seemingly stopping all actual work to hone in on a high profile popular figure to make an example out of is not exclusive to Street Pop & Nigeria – Drill artists in New York and the U.K. have suffered similar trials, for simply channelling the realities of where they’re from.

In the past, Naira Marley’s detention by the EFCC could have been a death knell for his career, however, the controversy fuelled an unprecedented run. For long, the music inspired by street realities had come with nihilistic themes that the mainstream grew uncomfortable with, but Naira Marley’s success was growing confirmation that unconventional perspectives could be shared and widely recognised without being overly bothered by puritanic reactions.

When Zino speaks about Naira, there is an air of admiration in his words. Reminiscent of early clips of Drake speaking about Lil Wayne, it must be some experience being signed to an artist so pivotal to the entire movement and sound one is a part of. Whilst 2019 was all about Marley and him alone, his label Marlian Music has become the bedrock of Street Pop, housing not just Zinoleesky, but other rising acts like CBlvck, Mohbad, Emo Grae, and of course, Rexxie, the man behind many of the hits during Naira’s 2019 run.

Christened Eze Chisom, the Anambra-born beatsmith quickly became integral to the success of the post-2018 street sound with era-defining production on Chinko Ekun’s “Able God” and Zlatan’s “Zanku (Leg Work).”

“My Journey into Street Pop started with Zlatan”

“My journey into street pop started with Zlatan,” Rexxie says when we speak one morning in August. “Zlatan already had that originality, you could hear it on “My Body,” the song he did with Olamide.” Long a student of the music game, Rexxie discovered that a lot of street pop music was heavily bolstered by its jarring instrumentals. “For me, when I heard street pop two years ago, I understood why mainstream listeners wouldn’t pay attention to it,” he says. “The streets were comfortable with how the sound was at that time, they just wanted to hear those high-tempo sounds and the lambas. But I came up with the idea of translating it in a way that even skeptical music listeners would want to listen and dance to this. If you pay attention to songs like “Able God,” you’ll hear the slicker melodies, as they’re saying their lyrics, I was following it up with rhythms.”

When Rexxie began rising to prominence, the signature sound associated with street pop was shaku shaku, a guttural brand of music that drew inspiration from the South African-originated dance subgenre, Gqom. But the producer’s entrance heralded a more compelling mutation. “When I had the opportunity to work with Zlatan, I shared my ideas with him and he liked it. We tried it with “Zanku” and it just worked from then on,” Rexxie shared with The NATIVE. As much as the Zanku sound was patented and became highly recognisable, it sparked a creative rebirth that gave street pop far more sonic range than it had in past years. By the beginning of 2020, sceptics started to forecast the phasing out of the de rigueur street pop sound — “you can’t make a genre out of a fad,” a prominent music critic stated at the time. Defying the odds, however, this era of street pop has only continued to evolve creatively, as many newcomers and veterans alike spin their iterations on the sound and source out new influences.

*****

Late in 2020, Rexxie released the anthemic “KPK,” an Amapiano-inspired smash hit featuring Marlian Music’s Mohbad. The track represented another dimension in the sprawling reach of street music as it enveloped other genres around it. “I’ve actually been listening to Amapiano for a while because street music has a lot of similarities with South African sounds,” Zinoleesky explains, “and I try to stay informed with what’s happening over there.”

Understanding street pop’s co-opting of influences from across cultures is important for identifying why it is at its most diverse and inventive at this time. In the past, street pop used to be mainly one-dimensional, hampering its staying power. In the mid-to-late-2000s, musicians like AY, Lord of Ajasa and 2Phat were articulating street life via indigenous bars that made rap the primary driver for street music. That set the tone for the short but impactful rise and reign of DaGrin, whose legacy helped pave the way for the decade-long incursion of street rap which in turn hybridised into street pop. By the middle of the 2010s, artists like Oritse Femi and Small Doctor became avatars for the burgeoning sound, however, street hop remained a catch-all term for music representing the hood.

*****

As the new generation of street pop stars start to become national fixtures, the tone of their music is increasingly influenced by the changing landscape of their lives, offering constituents of the streets a portal into life on the other side. On his latest project, ‘High Tension 2.0’, Bella Shmurda documented the thrills and joys of upward mobility with language and intonations that are readily accessible to the streets; despite his successes, he still wants to motivate. “I make my music for believers, for people that understand and are ready to move,” Bella says. “My creative process is lifting souls, my creative process is being a comfort, my creative process is to help with my music, at least—if that’s the only way I can help.”

For Zinoleesky, the broader reason he makes music is similar. “I’m from the streets and I want my people to know that I’ve been through what they are facing and at the end of the day it can all work out,” he simply offers. Areezy, who’s modestly popular in hoods on the deeper parts of Lagos Mainland, also believes his music offers this same inspirational effect. “I’m not the biggest artist, but my level has changed in the few years since I started making music, and I just want people to know that they, too, can upgrade,” he says.

The success of Bella Shmurda and Zinoleesky, alongside ascendant colleagues like MohBad and Barry Jhay, heartens Rexxie who insists that despite all their success, these artists remain deeply committed to the communities that raised and first accepted them. “Everyone has artistic goals and all but they still have to live their realities and we are all connected to the streets one way or the other,” he notes. “Street music is something that cannot be taken away from its roots. Not everybody is going to be able to make it out, so the sound will always be alive in its own way.”