Credits:

Editor-in-Chief: Seni Saraki

Editor: Adewojumi Aderemi

Creative Assistant: Ada Nwakor

Community Editor: Tami Makinde

Editorial Consultant: Matthew Chukwudi Nwozaku

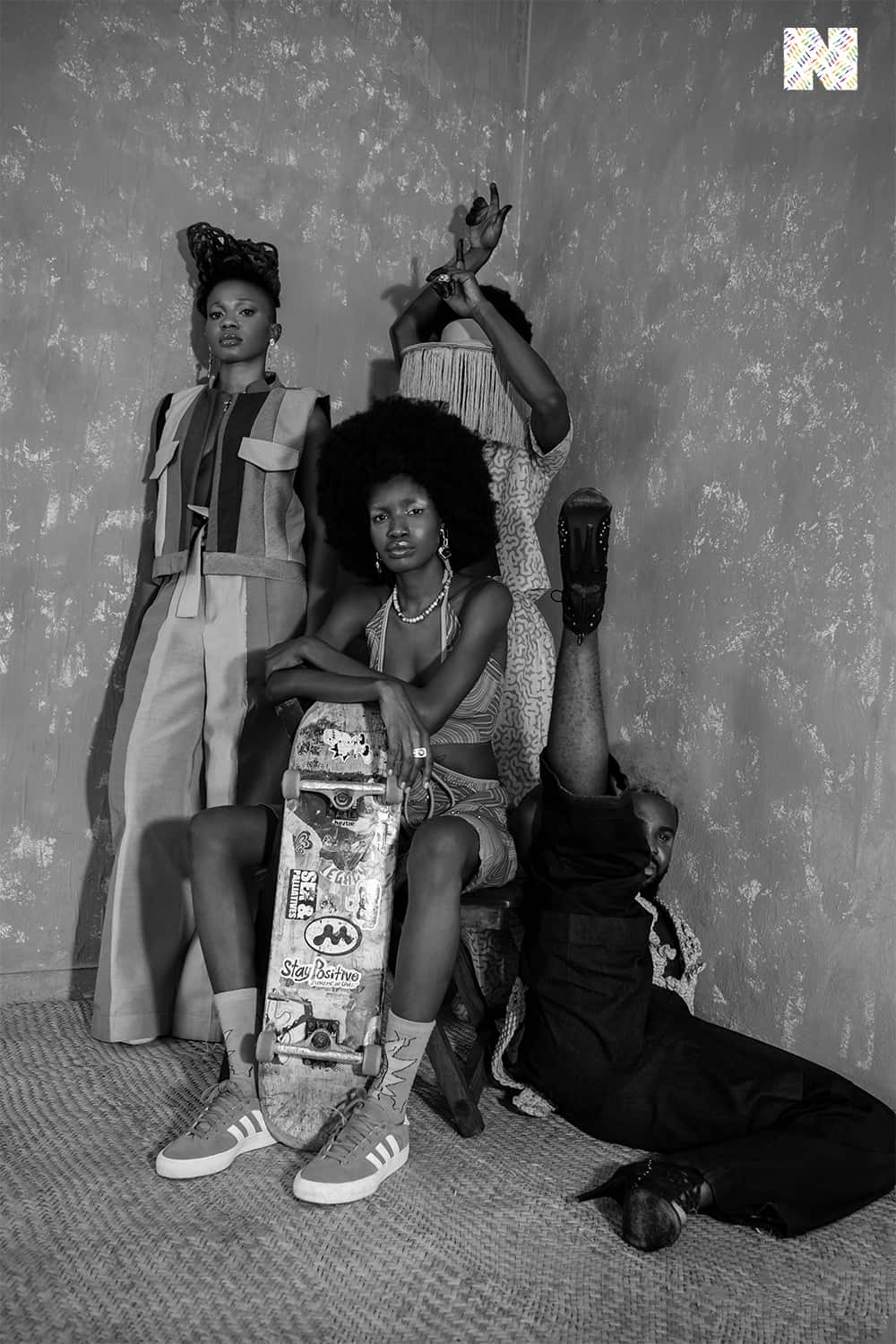

Photography: Stephen Tayo

Set Design: Ayo Lawson

Lighting: Ifebusola Shotunde

Photography Assistant: Henry

Set Assistant: Yusuf Karim

Styling: Ashley Okoli

Styling Assistant: Demola Mako

Make-Up: Ayopo Abiri

Make Assistant: Cvntai

Hair: Enigbonjaye Funke

BTS Video: Jola Adeboye

BTS Photography: Wonu Osikoya

Location: Fluid Locations

Rarely will one encounter a depiction of African culture without music and movement instructing representations. Throughout our history, evident in our traditions and customs, music has been a unifying, empowering and healing tool for our people, deployed in a variety of contexts, whether they be mournful, celebratory or sung through labour. Though we are relegated to racially charged categories, such as “urban” or “World/Global” music – the latter, a harmfully heterogeneous grouping that places incomparable sounds from diverse musical cultures in competition with one another – African people, Black people are easily considered custodians of music.

Hip-Hop is arguably the most influential genre in the contemporary soundscape, and prior to it’s increasing popularity through the years, Black people helmed Jazz. Engendered in late 19th century New Orleans, black instrumentalists would improvise melodies during parades, given they couldn’t carry sheet music along with them. Before that, the spiritual songs by African slaves on the field had informed what many now consider to be the white man’s genre – Country – owing to the violent erasure of Black people and their voices, especially in the South. Regardless of our differences, our music has touched each spherical corner of the world, testament to its innate relatability to listeners everywhere.

Whether instrument led, chants and a cappella choirs, or the sonic productions we’ve become accustomed to in modern times, whether it’s in a language we understand or one we are entirely unfamiliar with, music, like most experiential artforms, has an ability to reach inside of us, resonating with our deepest selves we might not even be consciously aware of. Stimulating several different parts of our brains, music arouses rewards, awakens memories and alters our mood and spirit. Music is a powerful resource, and those who wield it are powerful beings. With a deftness for using their life experiences, their joy, their pain, their questions, their certainties to galvanise others, these are the gifts Tobean wishes to share with the world through his musical artistic expressions.

“It all started from wanting to feel what it is to be me, on a level that doesn’t feel like I’m following somebody’s manuscript. I had so many questions, I was so curious, thinking, ‘yeah, I’m about to step into this world, how do I fit in?’”

Long aware that his spirit is intrinsically bound to the flow of sound, accepting his fate as a sonic auteur came with the trials his predecessors have lamented through their own emotional releases. “I have a father who is a singer-songwriter, so that in itself caused my imposter syndrome with creating sound,” Tobean reveals, eager to overcome this insecurity and release more music. Intimidated by the idea of having to fill another person’s shoes, Tobean leaned on his family, who were able to show him the diversity of existences one could lead. “They were enough to get me on to a path that led me to my soul and searching for my soul’s path,” and from there, he was able to accept his calling as a music-oriented creator, drawing out the divine feeling of harnessing beauty and interpreting it in ways unique to him. “Of course,” Tobean reminds us, “sound in itself is [an aspect of beauty].”

“I have super intense love for music and it was just something that moved my body. Even when I felt so disconnected from my body – because there were years of my life when I felt very disconnected from my body – when music comes on, no matter what it sounds like, my body moves, legitimately moves.”

In the conservative setting that most Nigerian children grow up in, life is tainted by absurd dichotomies that are separated by needle thin lines, hardly distinguishable to even those who ascribe to these dualities. Though there was a side of Tobean’s family that supported his affinity for movement as a child, his foster parents were ones to abide by arbitrary conventions, abusing him for his dancing passions, “they didn’t think [dancing was] something I should do.”

Dancing is a skill, it is also an activity for fun and leisure, but only a certain type of dancing is considered a skill worthy enough for professional pursuit. Even then, there are certain frames of professional dancing that are considered lowly, whilst other largely similar dance practices are heralded as the pinnacle of culture. As children, these binaries are instilled in us as a guide to the right way of life, but as queer people growing up, these purported ‘morals’ contradict our very identity. Alongside the internal conflict innate in finding one’s soul in a polar world came external oppression from Tobean’s foster parents, an amalgamation of pain that only music could release.

“In a sense it still all just boils down to my healing,” Tobean tells me of his inclinations toward artistic communication “through sound and movement and visual expression. I am really eccentric and I have a lot of pain, so I am using sound for my healing.”

A legitimate means of therapy, music is a healing force, capable of leading human beings out of their dark moments. When we listen to songs that eerily reflect our exact circumstances, or hear sounds of prosperity from people whose lives started out similarly to ours, the music we consume has the power to uplift us, inspire us and comfort us on our healing journey. For the artists behind the music, these effects are not dissimilar. Tobean, like Tems or Tupac, uses sound to journal his pain, working through his thoughts with the flow of the percussive elements that force his arms and feet into an uncontrollable movement. Watching Tobean’s waist and limbs glide in defiance of the stagnant Nigerian humidity is watching Tobean purge himself of the pain he’s accumulated, one bead of sweat at a time. A perfectionist guarding his sonic releases closely, until he believes he is presenting his best at its best, Tobean has only one single released, exclusively on YouTube Music. A collaboration with Tigran, Tobean’s “Induction” is a mystic and mysterious instrument-led number. Over the moody electronic beat, kept in time by a rhythmic bass guitar, Tobean supports the track with abstract wails, belting his inner pain into the dark night this mystic song illustrates. There is no doubt that hearing Tobean’s musical output in the future will be a similar medicinal dose of relief that will inspire us to connect with our soul like he’s finally done with his.