In 2018, Naira Marley embarked on a chaotic two-year run which included; court cases, police raids, a stint in prison, scene-stopping visuals, and sold-out shows – all punctuated by a string of inescapable and undeniable hit records. By the end of it, he became arguably the biggest, and definitely the most divisive star the country had seen in years.

This is the Inside Life, told during the peak of Nigeria’s most misunderstood superstar.

LAGOS – “People say ‘Marry Juana’ blew me.” Naira begins through a disarming chuckle that would become a signature tell before one of his many record-straightening statements throughout our day together. “People say ‘Issa Goal’ blew me. People say EFCC blew me. But it was still me. The whole time, it was me. I didn’t stop, I kept going. If I stopped after ‘Issa Goal’ I wouldn’t be here right now. If I stop now, I will probably be irrelevant in a few years. I can’t stop.”

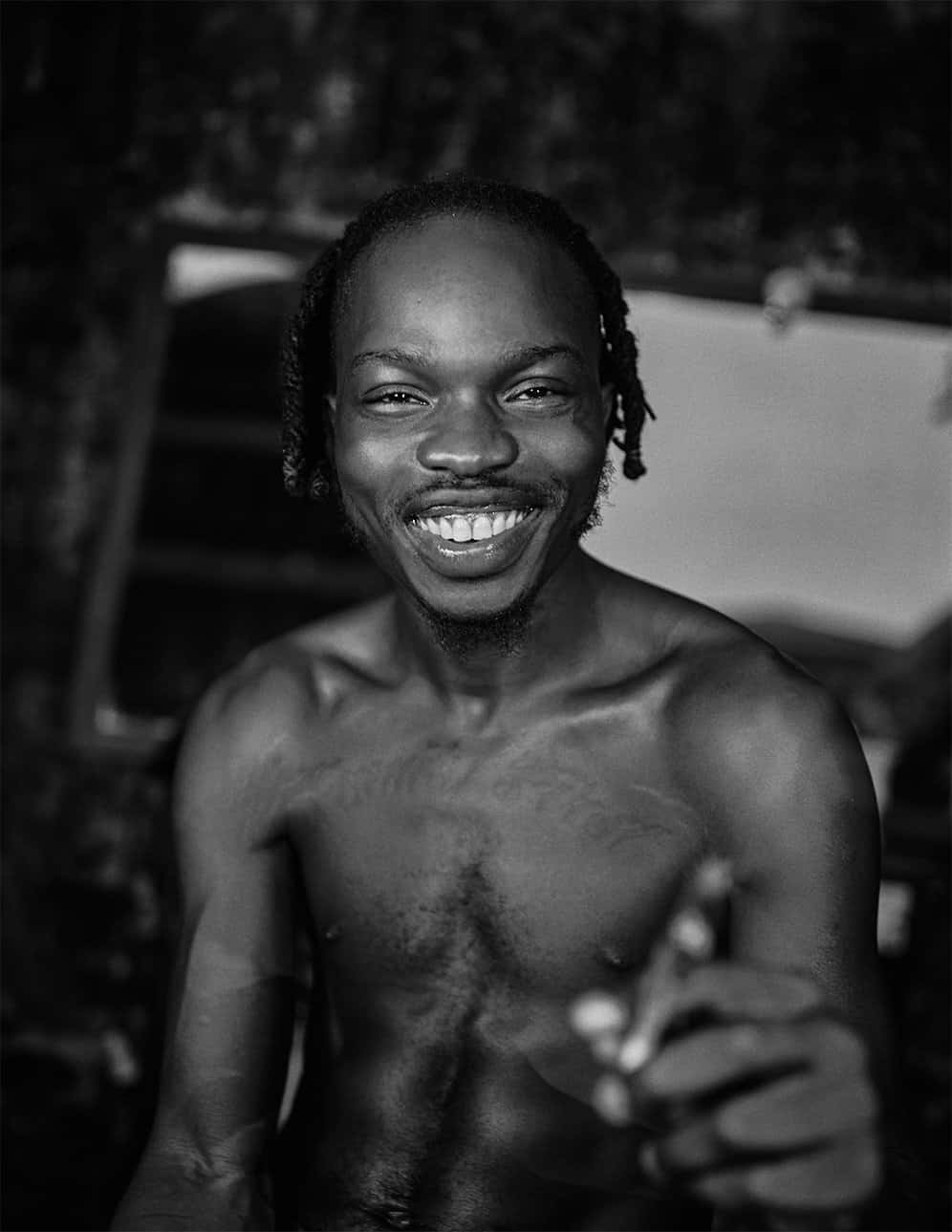

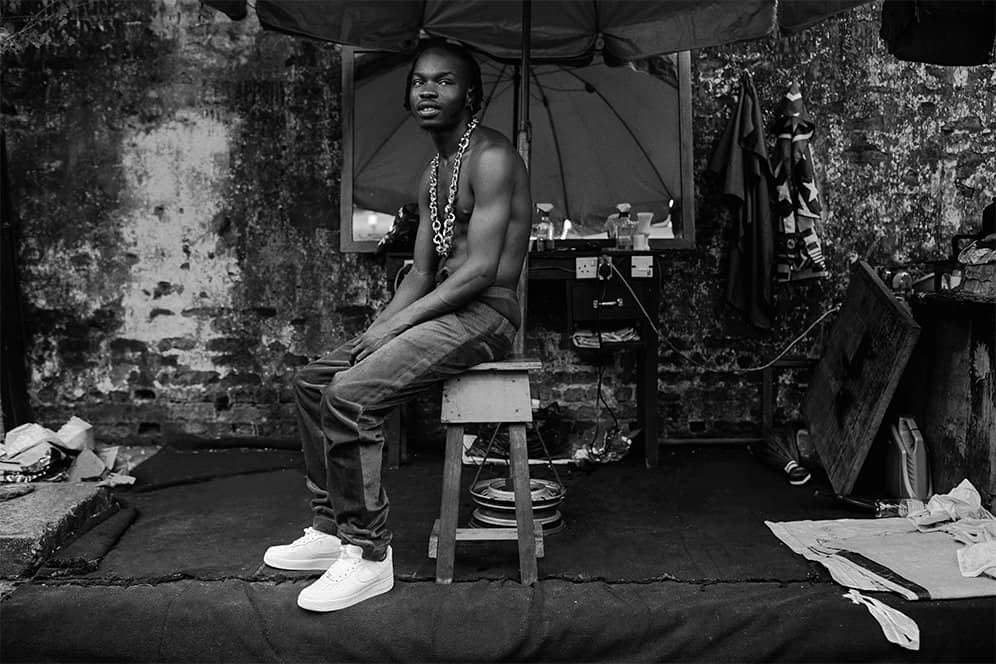

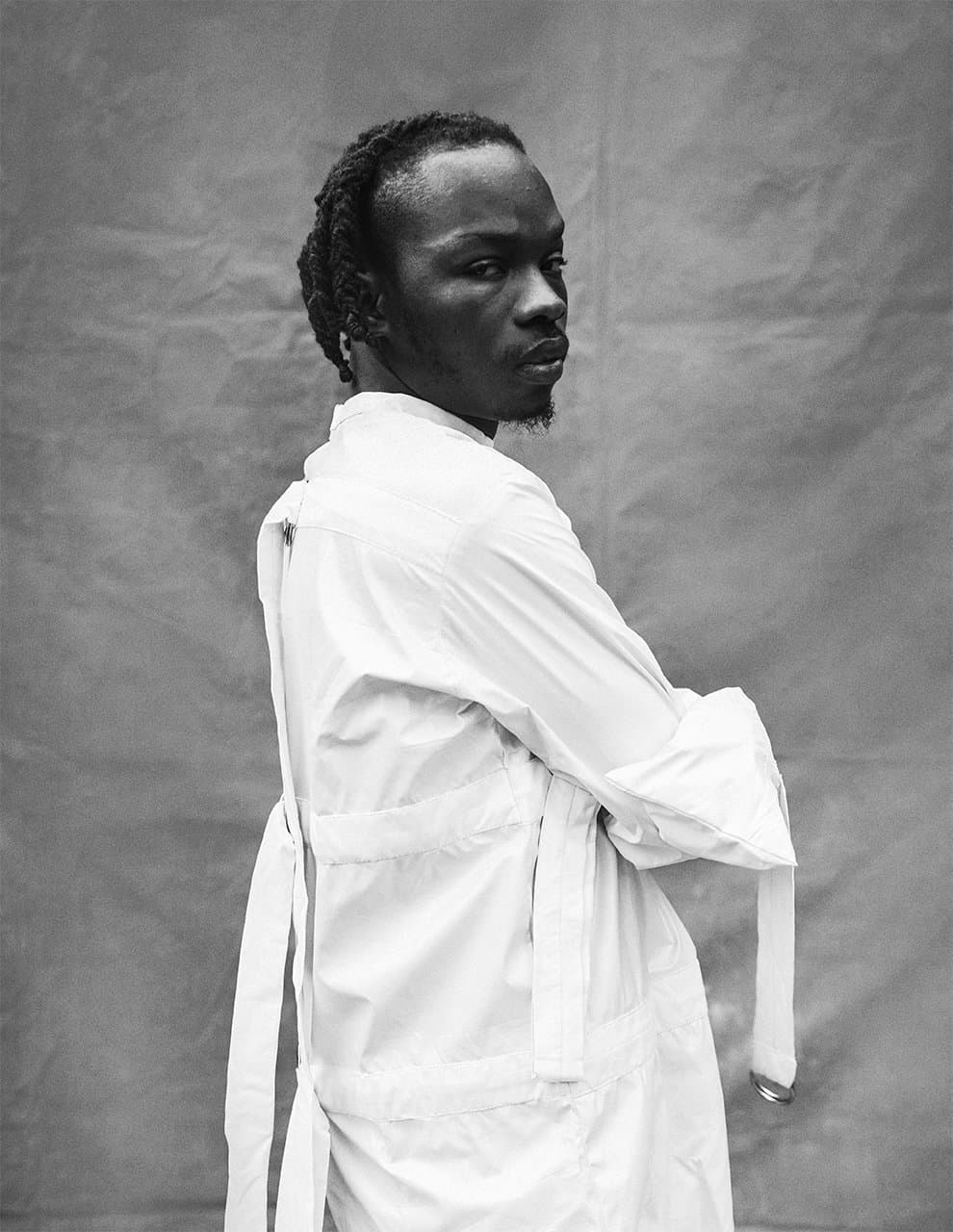

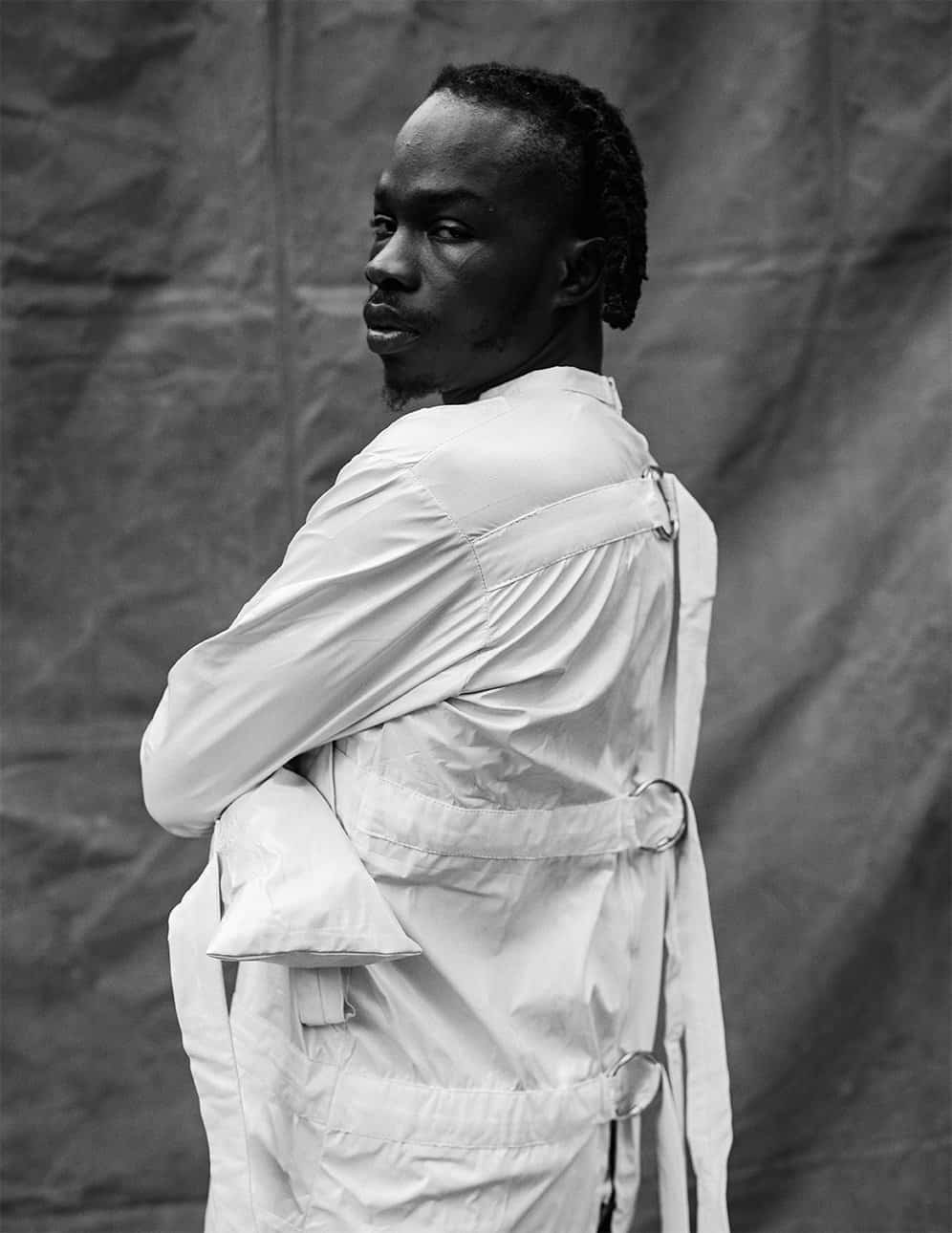

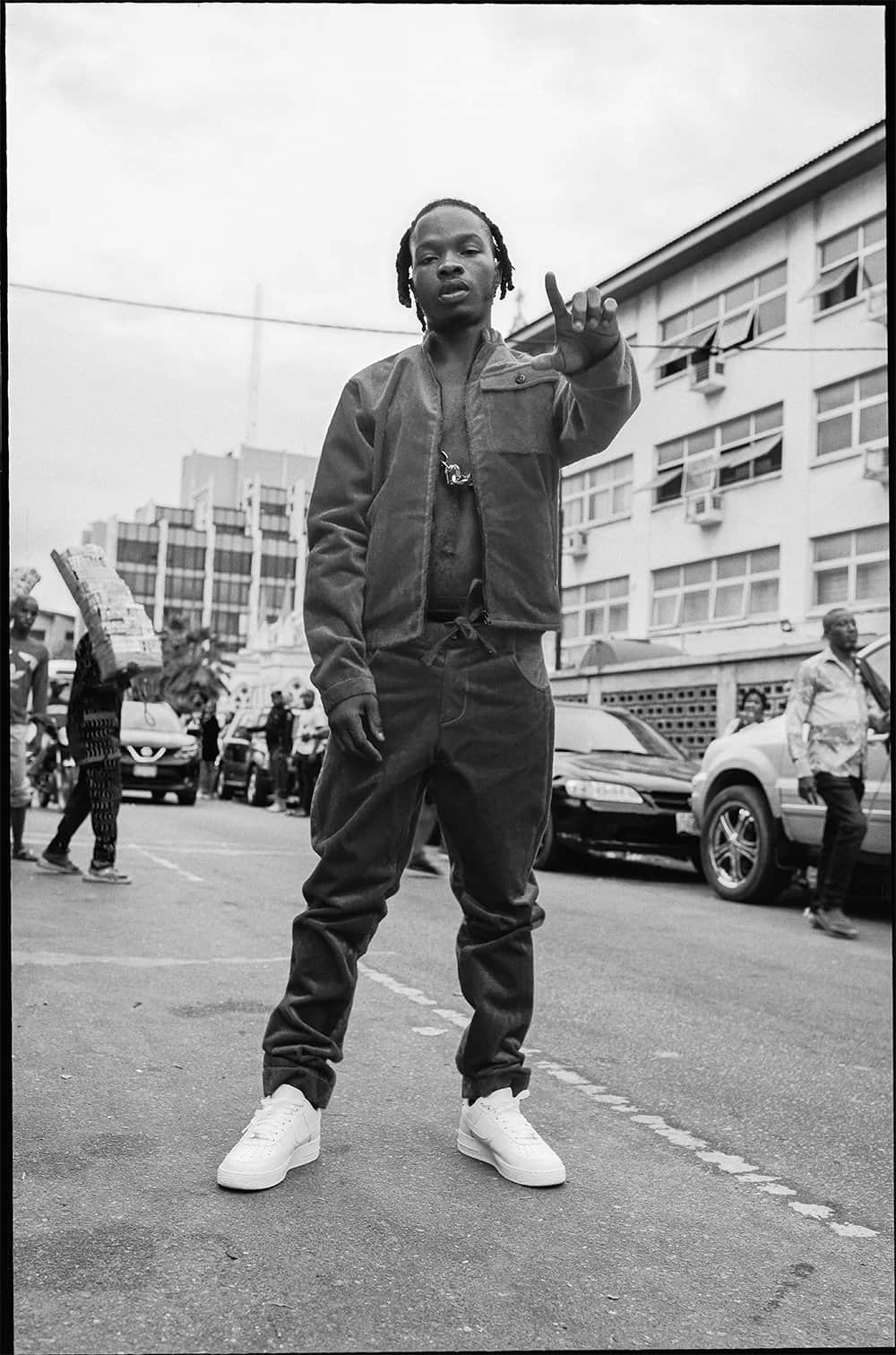

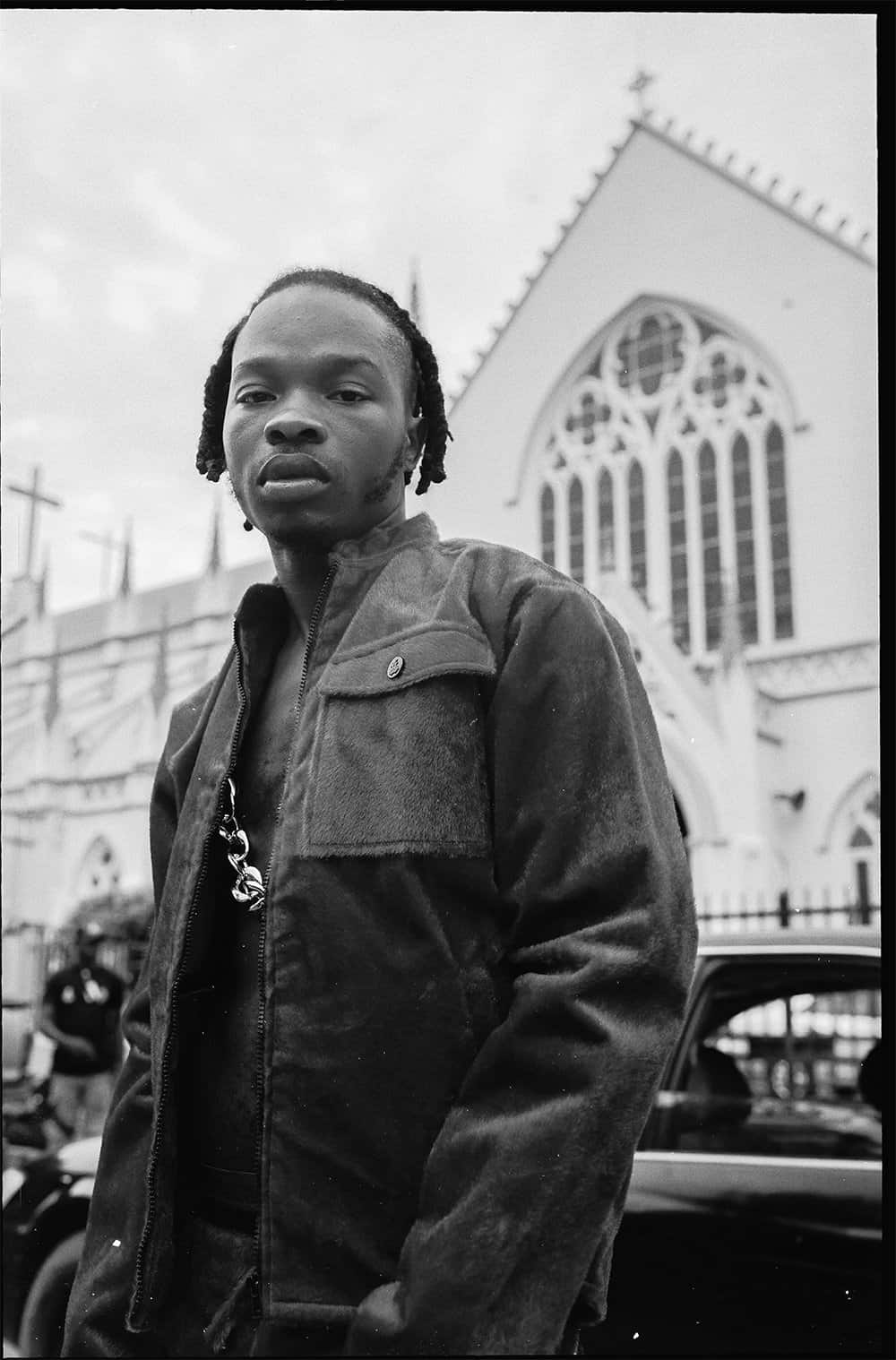

It’s 5:40PM on a relatively quiet Thursday evening for a December in Lagos, and Naira Marley has just arrived at the set for this cover shoot, originally scheduled to start at 2PM. Hopping out of his two-door Porsche Panamera, with an SUV trailing behind filled with his team, he slowly scans the street-long set for the day. We’re on Broad Street, Lagos Island, with the storied Freedom Park being the base for cast and crew. The irony of this historical landmark being the location for a shoot with The Leader of the Marlians is not lost on anyone. Now well known for all-night fetes and musical showcases used to be an infamous a colonial prison, which held Nigerian political icons such as Herbert Macauley and Obafemi Awolowo captive in the early 1900s. Once a brick and mortar institution built with imported British bricks to enforce stability, and designed to quite literally curtail freedom of speech by imprisoning the most influential anti-colonialist figures, Freedom Park has been transformed into a creative hub, celebrating the arts and culture of the city.

As Naira walks down Broad Street, he’s flanked by Ebuka Nwobu, the producer for the day, who talks him through the different scenes and looks he’s expected to be in. Somewhat apologetic for being so late, Marley is keen to make the most of the time that remains – with photographer Manny Jefferson already worried about the diminishing natural light, our cover star darts straight into the changing room. The perimeter of the set is gradually being surrounded by passer-byes finishing work, trying to get a peek of what’s being shot on this famous road today. Whispers fly around and within 20 minutes, what started as a curious group of onlookers, has now grown into a full blown audience, waiting to see if what they’re hearing was true. Emerging in an Ifeanyi Nwune cosmic-red velour tracksuit set, with his music already blaring out of the sound system, the rumours were confirmed

Naira Marley is indeed home.

The Making of Naira

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact moment in time when Naira Marley – known to his friends simply as “Nai” – started taking music seriously. Moving from Nigeria to London before he was even a teenager, Naira grew up in Peckham with his family. Studying law and business for his A-Levels, he openly admits he never saw music as his singular path in life: “Ten years ago when people asked me what I was going to be, I didn’t know. I was studying, I was just trying to finish college and play football. I was really good.”

Do you still play?

“Nah, I smoke too much now. Ten years ago, I just wanted to make it. I never thought it would have been [with] music”

And make it, he did.

Ten years on, and Naira Marley has charted an unlikely path from the streets of Peckham to the top of Nigeria’s music pyramid. Championing a distinctly homegrown sound and leaving a trail of hits and controversial incidents in his wake, Naira Marley has gone from just another rapper to one of the most recognisable faces (and voices) in the country. But to truly understand the young legend we see today, it’s imperative to look back to his formative years in London. The early signs were there that he had something special, but as is often the case with many mercurial talents, it requires a perfect storm for their star to truly soar. You would never have known it though: to the man himself, real name Azeez Fashola, he has always been a star.

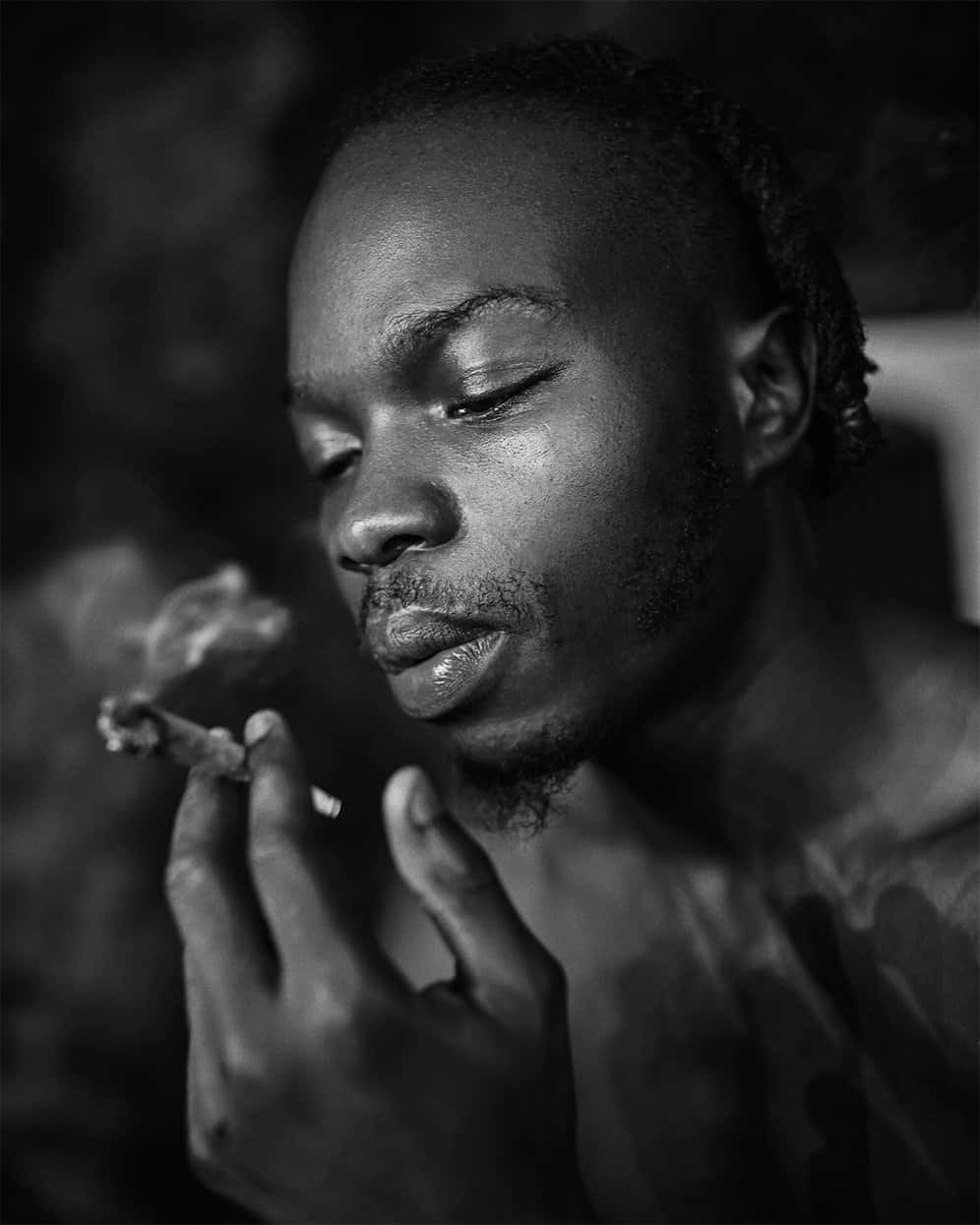

It’s 9:30PM now, and while we wait for our post-shoot meal at a nearby restaurant, Naira invites me into the backroom of the establishment for a quick smoke break. ”It’s only now that I realise I wasn’t even a superstar before,” he says calmly, lighting up the biggest joint I’ve ever seen in real life. “I’ve always believed I was a superstar, since those times, but now it’s more intense. I can’t escape it.” This is a sentiment also echoed by Ian McQuaid, Head of A&R at MOVES Recordings, the label that kickstarted Naira Marley’s career in the UK: “He was never not Naira. He would be acting like a superstar at the Bagel King in Peckham.”

Naira’s first taste of fame from music arrived with the release of “Marry Juana” in March 2014 – a playful debut song, which until this day, is a cult classic within the UK scene and a favourite for Marley’s day one fans. An ode to his favourite plant, it has some early markings of the Naira we hear today, such as the innocent-sounding double entendres like “money on your head like Naija party.” More than that, it was arguably the birth of the first wave of Afro-Bashment, a sub-genre that would go on to dominate dance-floors all over the UK for years to come. Although the song never took off on radio or hit the charts, it was undoubtedly a cultural reset of sorts. Many young Africans in the UK were struggling with their identities and the true meaning of home, but the emergence of this sound – pioneered by the likes of Naira and fellow South London rapper, Snekabo – opened up new avenues for dual-national kids to be themselves.

“They say I’m a pioneer, and I get that… When I started, a lot of people followed the trend.”

Naira’s innate ability to innovate his sound is a recurring theme throughout his career thus far, and according to him, these seismic sonic shifts are usually the result of his surroundings and musical influences at certain moments. Around the time “Marry Juana” was released, Naira was lending his voice to various genres through a slew of sporadic drops, he himself admits were not borne out of a well-thought out, strategic plan: “I was just making music for fun, just for me and my friends, and the people who were feeling my music. I would drop one song and they would be like ‘ahhh, drop another one’, and then I’d drop another one.” He pauses for a second, seemingly nostalgic of yesteryear. “I guess that’s still happening now,” he says with a wry smile.

Despite the lack of structured releases, Naira was unknowingly in the closest thing to a musical hyperbolic time chamber – testing flows, flexing with cadences, riding beats from multiple genres – what was simply fun to a young Nai, was preparing him for his next sonic shift. After the success of “Marry Juana”, Naira dabbled in more Nigerian-inspired sounds, with tracks like the 2015-released “Praise & Worship” becoming a blueprint for what the UK music industry now refers to as “Afro-Swing”: essentially, a fusion of Afropop and UK Rap. Despite the contentious genre name, it’s a sound which currently houses some of the most exciting black talent in the world right now: artists like J Hus, Young T & Bugsey, and Pa Salieu to name a few, are all considered to fall under the umbrella. Naira is very measured when discussing his influence in this wave. “They say I’m a pioneer, and I get that. It’s like Giggs. Giggs wasn’t the first rapper, but he broke it down and created a lot of rappers that came after him. That’s the same thing with me. When I started, a lot of people followed the trend.”

As the sound was picking up steam both in the UK and back home in the big music cities such as Lagos, Accra and Nairobi, one could have expected Naira to capitalise on a movement he pioneered. But as we have come to find out, expect the unexpected with Naira Marley. Inspired heavily by the Chicago Drill movement, specifically the legendary Chief Keef and the late, great Speakerz Knockerz, Marley felt he had to keep it real, and make music that was the most accurate soundtrack to what he was going through. “The music from Chicago inspired me to talk about my own life. It was violence in those times, all that UK gang-gang lifestyle. I was young and growing up, that was my life.” Whilst UK Drill artists in 2020 have made entry onto radio, festival stages and playlists, it was not quite the case back in 2015. Much earlier in his career, Marley dropped and ode to the GBE head honcho entitled “Like Chief Keef”. Premiered on GRM Daily to mixed reviews; it was less a play at stardom, but more a revealing snapshot into the mind of an artist still refining his sound, taking in influences, and figuring out the world around him. Years later, not deterred by his first foray into Drill, Naira did a 180 on the “Marry Juana” sound that had given him a spotlight, and with the help of MOVES Recordings, released his next seminal record: “Money On The Road”.

“He’d been massive with ‘Marry Juana’,” McQuaid says via FaceTime, “People used to stop him in the streets and get photos with their babies. In Peckham, in his ends, he was a king anyway…I saw him perform live once and he was just such an incredible talent, it was so obvious. I’d tell anyone who’d listen, this guy is going to be a massive star.” Marley himself admits that he needed some cajoling to commit completely to music, “There’s money in music, and everyone just kept telling me I need to take it seriously because I can make it.”

Leaning into Drill for “Money On The Road” came with its hiccups – Naira’s two co-stars on the song were both doing time when the record was actually released, and they couldn’t even get a video shot. That didn’t hinder the success though: McQuaid says not only was it a defining moment for Marley, but for his label too, and still pays the artists involved from the “millions and millions of streams” till this day. More than the streams and royalties, “Money On The Road” opened up yet another sound pocket to explore, combining the sensibilities of both Drill and Afrobeats in a way that had never been done before. The new sound provided ample opportunity for previously marginalised acts to garner mainstream attention and critical success: none more so that the sprawling Nigerian-Ghanian origin group NSG, who have since taken advantage of this new avenue, with their perfect blend of Afropop melodies and cadences, mixed with the grit and ingrained camaraderie of UK Drill.

Naira Marley was a superstar in the place he called home. For some people, that’s enough. You hear stories about local champions, enamoured with the adoration of their immediate neighbourhood, but at the same time, handicapped by it. The hunger is gone. They’ve already made it bigger than anyone ever thought they would. Not Naira, though. He had barely begun. And his next move would be the one to start the fire of all fires.

Issa Goal, But It Nearly Wasn’t

Hit songs are peculiar things, you can never really predict them. Even the prolific, seasoned #1 getters will tell you: you never really know 100%, until it hits. Wizkid’s “Ojuelegba”, considered to be a watershed moment for Afropop, and regarded as one of the best songs from the continent in recent history, was originally a 15-minute Fela-like freestyle. Lil Wayne’s electric, remix-inducing single “A Milli”, was intended to be a recurring skit-like song for his album, and to further show how it was first prioritised in his roll-out, the video for the track was recorded in one-take, between breaks whilst shooting a big-budget visual for another single. This is not to say that the artists involved with making these songs didn’t appreciate the quality, but there is a long road from what sounds like a good song, to a bonafide hit record.

Naira had seen success with “Money On The Road”, but what came with his mammoth hit “Issa Goal”, was something completely new. Speaking to the producer of the song, Platinum Toxx of Studio Magic, he says they had no idea it would become as big as it did. “Naira and I had been working on quite a few tracks at the time. We were introduced by Wande Coal, and we just hit it off,” he explains via voice-note. Naira, for once not the pioneer of a trend, had been paying close attention to the Shaku Shaku dance-wave that was bubbling under, and was intent on making an anthem in its vein.

Dances have been the biggest catalysts of Afropop in the last decade, as a consequence of the emergence of social media and video-sharing on the continent. Routines have become a great connector between Africans all over the world, and act as an easy gateway for music lovers everywhere to access the sound. Whilst the early 2010s saw the emergence of dances directly tied to songs like Iyanya’s breakout “Kukere” (2012) and Davido’s Thriller-like “Skelewu” (2013), the latter years of the decade produced routines that lived and travelled far beyond any one track. Whilst dances such as “Shoki” and “Alkayida” enjoyed varying levels of success, the aforementioned “Shaku Shaku” swept across the entire continent, partly due to its versatility and adaptability to almost any rhythm.

Determined to tap into the latest dance-craze, Naira and Platinum Toxx set up shop at legendary Lagos rapper Olamide’s London residence. “We made the whole thing from scratch in one night,” Toxx recalls of the creation process for “Issa Goal”. “At the time, Naira was transitioning from being a UK artist to the person he is now. It was super hype in the studio, but we still weren’t expecting it to do what it did.” The result was a bouncy, joyous ode to what is infamously referred to in Nigeria as the opium of the people: football. Anchored by the consistent sonic bedding provided by Studio Magic, Naira Marley trades bars with Olamide and Lil Kesh – two artists extremely familiar with engineering street smashes – and shows he has the cadence and ear for what he calls “pure Afrobeats”.

“I wish everybody the best, but nobody is touching me right now. Nobody.”

Naira Marley and his collaborators have made a hit, the problem is, they’ve made it too early. It’s 2017, and with the World Cup coming up in the Summer of 2018, Naira’s A&R senses an opportunity to truly explore the full potential of the record. There was a common consensus that dropping it in December would circumvent the possibility of the song leaking, however, they had to keep the momentum going until the start of the World Cup. To this end, Naira bagged a dedicated football PR team, who was working overtime to get “Issa Goal” placements in the UK, such as on the BBC’s official World Cup coverage. Around the same time, Nike and The Super Eagles linked up to drop one of the most iconic jerseys in World Cup history – it was all aligning for Naira’s song to be the unofficial-official soundtrack to the coolest team at the tournament.

Naira and his label recognised this, and knew a big part of the song picking up and maintaining steam was to get the music video right. They knew the video had to be shot in Lagos, and they also knew it needed to be promoted in America as well. This resulted in a premiere with The Fader, who paid for most of the video which saw Naira proudly waving the Nigerian flag as he hung out of a car driving down the heart of Lagos, a location that seems like a favourite of his, Broad Street.

But, honestly, the whole thing might not have happened. As Naira Marley was counting down the days till he flew back to Lagos for the first time since he was a kid to shoot the all-important visual accompaniment for the World Cup anthem-to-be, the final piece to the marketing puzzle, a foe that would later become more familiar to him back home, struck: the police requested Naira’s presence in court.

The story goes, Naira was pulled up for a “driving offence”, and because he had ignored the previous attempted correspondence, this minor offence resulted in a palm-wetting visit to the court house. As Naira took his seat, the judge promptly stated that they intended to throw the book at the rapper, with a 12-month custodial sentence. Then, it became serious. What they thought was one speeding mistake, was allegedly the second driving offence on Azeez “Naira Marley” Fashola’s record. The judge stated that this triggered an automatic process, which could only result in jail time. Just before what was meant to be his breakout moment, it seemed it was all about to be taken away – or at least severely delayed. This is a common occurrence in the history of Hip-Hop and Drill music, as when an artist starts gaining notoriety, the authorities seem to watch them even closer. Marley himself saw it happen at close quarters, to his “Money On The Road” collaborators from Drill group Harlem Spartans. Other rappers like Bobby Shmurda and Rowdy Rebel had barely finished drying off the celebratory champagne, before finding themselves in trouble with the law.

Fearing for the worst, Marley’s defence was hinged entirely on the upward trajectory his career was poised for. And by divine intervention, it worked – Naira was let off without any jail time. One can’t help but put Naira in a Schrodinger’s Cat thought-experiment after hearing this story. What would have happened if Naira had to do the time? Could they have shot the “Issa Goal” video without him somehow? Would they have lost all their mainstream television placements? Would he still have the buzz when he got out? Would we be speaking about him today? It’s true that great artists always find a way to rise to the top, but even the legends have had their slice of luck: Jay-Z’s infamous plea deal comes to mind, when he was facing 15 years for the stabbing of an associate he believed leaked his album. Maybe Jay-Z would have still become the greatest rapper alive, albeit with a fifteen year break between albums four and five. And maybe Naira didn’t even need “Issa Goal”, and could have gone back into the lab after a year away, without missing a step. Context in mind though, both seem unlikely.

Naira himself seems to slightly play down the effect the song itself had on his trajectory. “I was already killing it in England before then, ‘Issa Goal’ just dropped at the right time,” he says, unwilling to let a single song define his ascent to the throne. “People say ‘Issa Goal’ blew me. People say ‘Marry Juana’ blew me. People say EFCC blew me. But it was me the entire time. I didn’t stop, I kept going. If I stopped after ‘Issa Goal’, I wouldn’t be here talking to you now. If I stop now, I would probably be irrelevant in a few years.” The defiance and self-assuredness is something many associate with Naira Marley without even knowing him, but what comes across the most is the brutal honesty and refreshing perspective he has when looking at his own life and career. He’s not saying these key moments are irrelevant to his success, but he’s simply reaffirming the facts: the one constant between all of the songs, all of the dances, all of the controversies (more on that shortly), is him: Naira Marley.

The Marlian Era

Narrowly escaping a year-long prison stint, Naira was finally free to go to Lagos. Despite the fact that the trip was planned around shooting a video to promote “Issa Goal”, it turned into something much bigger. Beyond the record starting a run of songs that would turn Naira Marley into a near-deity, if there was truly one moment that could be labelled cataclysmic in Naira Marley’s onslaught on the Nigerian music industry, it was his return to Lagos. That was where he met Rexxie, and thus birthed another sonic shift, setting the ball rolling for the Marlian Era, and all that came with it. If the creation, and subsequent success of “Issa Goal” was opportunity meets fate, Naira’s musical direction thereafter was calculated and precisely-engineered.

As Naira continued to evolve as an artist, he would take elements of previous iterations and work them into each new reincarnation. This is clear to see in the release of his next record that year, after “Issa Goal”, the sparky “Japa”, his on-the-run anthem inspired by the events that nearly saw him end up behind bars. Declaring that he “ain’t gon stop”, accompanied by a tongue-in-cheek video where we see him on the run from the police, it’s easy to assume this is how he felt at the time. Following such a turbulent period, Naira did what Naira does best, emerging with another smash hit which took off in Nigeria’s singles-driven market and became the song of the official party season. Using the Drill sensibilities found on “Money On The Road” and “Like Chief Keef” days, Naira magnificently combines this with his rediscovered use of the Yoruba language on wax, further building upon the foundations of “Issa Goal”, to fully transition to “pure” Afrobeats. A major factor in this transition has been Rexxie, the Lagos-based super-producer known for reigniting the Street Rap scene with his Zanku-ready beats and bops.

“We went to Nai’s apartment to record a song with him, Zlatan and Lil Kesh,” Rexxie recalls, on the day he met Naira Marley in person. “Whilst we were waiting for Kesh, Naira said I should play him some beats. I knew he was making moves in London, but I wasn’t so familiar with his music, so I didn’t know what to play him,” he admits candidly. “I started playing a beat, and straight away, he just said ‘yes, that’s the one.’ He started writing immediately – a lot of people assume Naira just freestyles, but he actually writes everything on his phone. He started recording and I had never heard anything like it, it sounded so new. Everything came together and that was ‘Japa’. The first song we did together and the start of our journey.”

While Rexxie may view Naira picking the first beat he played as perhaps fate or coincidence, on further examination, it serves to further exemplify how, as Naira Marley evolved as an artist, the different parts of his career went along with him. Despite the genre differences between UK Drill showcased on “Money On The Road” and the Nigerian Street Rap leanings of “Japa”, the two songs share similar sonic elements in the make-up, specifically the tempo; the former clocking in at 105 BPM, with the latter pacing at 109 BPM. Naira himself undoubtedly did not know this on first listen, but it appears this may be why he gravitated towards the beat. Nigerian Street Rap is typically high octane music, dating back to the energetic “Kondo ” from the late, great Dagrin, to more or less Olamide’s entire hit discography. Again, Naira’s subtle but effective musical innovation here, aided by his now go-to producer Rexxie, would open up more new doors, and set him on his path to one of the most dominant single runs in the previous decade. However, in what seems to be a recurring theme for Naira Marley, trouble was just round the corner.

The problem of cyber-crime – infamously known as “Yahoo Yahoo” – is one which has plagued Nigeria for years. With victims both home and abroad, it is a crime sadly associated with Nigerians as a whole. The somewhat unspoken element of it is just how much the funds acquired from the crimes trickle into other industries. It was this point that Naira Marley was seemingly trying to make one afternoon in late April, which sent the Nigerian internet-world into mayhem. Speaking to followers on Instagram Live, he appeared to sympathise with Yahoo Boys, urging his followers to “pray for them”, so that they too, would continue to make their income. Despite the fact that “Yahoo Yahoo” has long since been affiliated with the music industry, whether behind-the-scenes or through crossover hits like Olu Maintain’s “Yahooze” or 9ice’s “Living Things”, Naira’s stream of consciousness was met with intense condemnation from his peers in the industry, the majority of the general public, and ignited a saga that would result in two hit songs, a very public arrest and imprisonment, and shift from famous to infamous.

There was so much negativity, but there was also so much love, and I was like do you know what? I can take the hate. The hate was giving me money, so eventually I just kept being myself.

As Naira Marley was being publicly castigated for what was perceived as his support for cyber-crime, he did what he always does: channels his real life into his music. Linking up with Rexxie and close collaborator Zlatan, they released the fittingly titled “Am I A Yahoo Boy”. A tongue-in-cheek response, littered with double entendres and one liners directed at those who called him out on social media. The song caught fire immediately. Opening with the iconic line, “See me see trouble, am I a Yahoo Boy”, utilising clever wordplay to namecheck Nigerian pop star Simi, who was one of the most vocal about the dangers of glorifying cyber-crime, Naira goes on to shuttle between Yoruba and English, in a defence of his views. Other standout, eye-roll inducing lines like “Emi hot male, mo fine gan, I’m not a yahoo boy/ but contact me at NairaMarley@yahoo.com”, sees him wink at the audience, claiming he is simply a handsome boy (said in Yoruba, to play off hot male + hotmail). This is just some of the lyrical flexing Naira displays on the record that perhaps goes unnoticed due to the dance-floor ready nature of it.

“The mindset in Nigeria has to change… I’m not committing a crime, I’m making music,” he says insistently. “ I could be telling a story from someone else’s point of view, so saying what I’m saying is not a crime. If it’s a crime, then they should come and arrest me.” Following the release of the accompanying video for “Am I A Yahoo Boy”, Naira Marley was arrested by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) for suspected involvement in cyber-crime. Since the case is still open, Naira is not able to speak in any detail about it, but he does maintain his innocence. Later in the year, he would send a tweet stating, “In Nigeria, they arrest you first, they will try and find out your crime after”.

A year prior, Naira Marley had avoided jail in England by the skin of his teeth, but this time, he was not so lucky. Incarcerated for nearly a month before being granted bail, the incident catapulted his celebrity around the country, and he revelled in it: performing the iconic Fela Kuti two-armed salute on the way to court during the bid. Upon release, Naira was fuelled by his imprisonment and the perception of being public enemy number one. He would again turn to Rexxie, to deliver his biggest song yet, and cause even more waves with its subject matter.

“‘Soapy’ was the song that solidified everything for Nai,” Rexxie says reminiscing. “He had just got out, and people don’t understand what he went through. It’s hard to relate to people after that experience. I found it so hard to speak to him, and he wasn’t speaking a lot then. The only way we could connect was the music. We were just in the room, not even looking at each other, but I was making the beat. When I was done, he already knew what he wanted to say, he already knew it was going to be a hit. Nai always knows. He had the idea for the dance as well…” And the dance is what had Naira Marley in the headlines again.

“Soapy” was Naira Marley’s jail-time memoir, detailing what went on behind bars in a Nigerian jail. An inescapable part of that,many claim, is the act of one pleasuring oneself, aided by… well, soap. As explicit and honest as the song is, the dance – the mimicking of the act repeatedly – was more vulgar than honest. Asking Nai about it, half-expecting him to double down, he insists that, contrary to popular belief, the dance actually mimics a different pastime in prison – rolling dice. “I didn’t ask anyone to be stupid about it, but you can’t control everyone and that’s Nigeria for you.” He seems, at first, genuinely apologetic about men using the dance to harass women, but implies the subject matter of his music simply just isn’t for everyone, recommending that perhaps music should be categorised as cinema is, with “comedies, movies for adults, kids films, and all that.” Ultimately though, he reverts to his default stance when it comes to the outside world speaking about him:

“I don’t care, man. It’s free promo. Look at me, I’m getting bigger and bigger.”

And bigger and bigger, he was getting indeed. Between May and September 2019, Naira released the quintet of; “Am I A Yahoo Boy”, “Opotoyi”, “Soapy”, “Pxta”, and “Mafo”; embarking on an unrelenting, inescapable onslaught on the music industry and every facet that surrounds it. For the rest of the year, Naira Marley was the hottest ticket in town. From weddings, to barbershops, to dance-floors, to stages, he reigned supreme, supported and upheld by his loyal fanbase he calls Marlians. “I don’t have any competition,” he says boldly, without any hint of a joke. “I’m not even playing games. There was Afrobeats happening before I came, but now everyone is following my sound. I hear so much of myself in all the music now.” Naira’s musical transformations over the years had led up all the way to this point. As much as he has a great compass on what gets the people going – whether in hatred of adoration – he seemingly always has his finger on the musical and cultural pulse. He was an early adopter of the Drill wave, before then pioneering what came to be known as Afro-Swing. Then, as the entire UK industry jumped on the two, he pivoted all the way to Nigerian Street Rap, giving the sub-genre a new lease of life, after Olamide had more or less carried it on his back (at least in the mainstream), since the tragic passing of Dagrin. Again, early, but somehow right on time.

“Naira is a musical genius,” says Rexxie, almost gushing. “We planned to change how indigenous rap music was perceived and we did that. We made it a lifestyle, and now everybody is on the wave. Everyone has different messages, but the sound is constant. Sometimes in Nigeria, we judge what it is good by how it is accepted abroad”. The producer continues, “why does that matter? Good music is good music. If everyone at home is dancing, why does it matter?” A few years ago, the mantra “Africa To The World” was parroted by industry folk and artists dreaming of global recognition. Now, inspired by the likes of Naira Marley and Burna Boy doing it their way, it is clear that the goals may be the same, but there are plenty of tactic options to get there. “Everyone is good in their own way, in their own lane.” Naira says, exhaling on spliff number seven of the evening. “I like their music, I enjoy their music. My music is different and I still need to get where I’m going,” he states, looking to the future, before coming right back to the present. “I wish everybody the best, but nobody is touching me right now. Nobody.”

Looking back to this whirlwind year of 2019, no one quite had a hotter hand than Naira. Everything he touched turned to a hit. Even when he unexpectedly switched it up on Davido’s sophomore album standout, “Sweet In The Middle”, with a verse in the perfect Queen’s English – something he hadn’t done since his reintroduction into the scene on “Issa Goal” – it went down to rave reviews, with viral videos hitting the timeline of groups screaming the lyrics at the top of their lungs.

“Five years ago? Nah I couldn’t imagine being here. Because I wasn’t taking music as seriously, it was just fun. But now it’s serious… Now, I care.”

Now, months later, with some declaring the death of Zanku – the dance and the music associated with it, which Naira Marley had become somewhat known for – what does Naira Marley’s legacy look like? Whilst Zanku as a sound and movement may not quite be in the cemetery just yet, it will undoubtedly end up there, like every sound before it. Music is a living organism, Afropop especially, constantly evolving and growing in different ways. Naira Marley himself has shown the ability to do this at will, so his survival on the top table of African music would not be vaguely surprising. But more than this, there is a slight obsession at home to declare the end of an era. It’s understandable, human beings love to look ahead – now, more than ever, that’s all we have.

With that being said, it’s wise to truly appreciate something for what it is: starting as a dance from the streets of Lagos, popularised by Zlatan and Chinko Ekun, Zanku became a global phenomenon, tapped into by almost every Nigerian artist of note. For that alone, the movement will go down in history as one of the most dominating in Nigerian culture. Naira Marley certainly would credit the movement to some extent for his rise to the top, all culminating in a sold-out headline concert at the prestigious Eko Hotels and Suites in December and the O2 Academy in Brixton in February.

Whilst many loyal Marlians were not able to attend the shows, it was a sign of just how far the boy from Peckham had come. Just over a year prior, Naira was flying to Lagos for the first time since he was a child. Now, he was at the top of the game. “Five years ago? Nah I couldn’t imagine being here. Because I wasn’t taking music as seriously, it was just fun. But now it’s serious, I can’t go to the shops, I can’t really get a job. Now, I care. I care about my record deal. I care about being signed. I care about shows. This is my hustle now, this is how I make money, you know?”

Naira has hustled his way right to the top of Olympus. Where he goes next, is anyone’s guess. He’s recently dropped a reassuring new Rexxie-produced single, “As E Dey Go” mid-lockdown, where he passes commentary on the mellow mood of the current climate. He’s also building up his label imprint Marlian Music – which he speaks passionately about – giving opportunities to young artists he believes in such as Zinoolesky, Mohbad, C Blvck and Fabian Blu who have since released their debut singles. As he grows older, he wants to spend more time with his four children, he laments “between the studio and shows, I don’t get to see them much, and they’re all so young.” Mention of his family is a rare glimpse into the personal life of Azeez Fashola during our conversation. It’s not that he’s guarded, but as does become the case with bigger-than-life stars, who they are under the lights slowly engulfs whoever they were beforehand. Some see it as rappers going “Hollywood”, but it appears as more of a coping mechanism. Sure, it’s great to have millions of people hanging off your every word and watching your every move, but in this generation more than any, there’s a gift and a curse to any blessing.

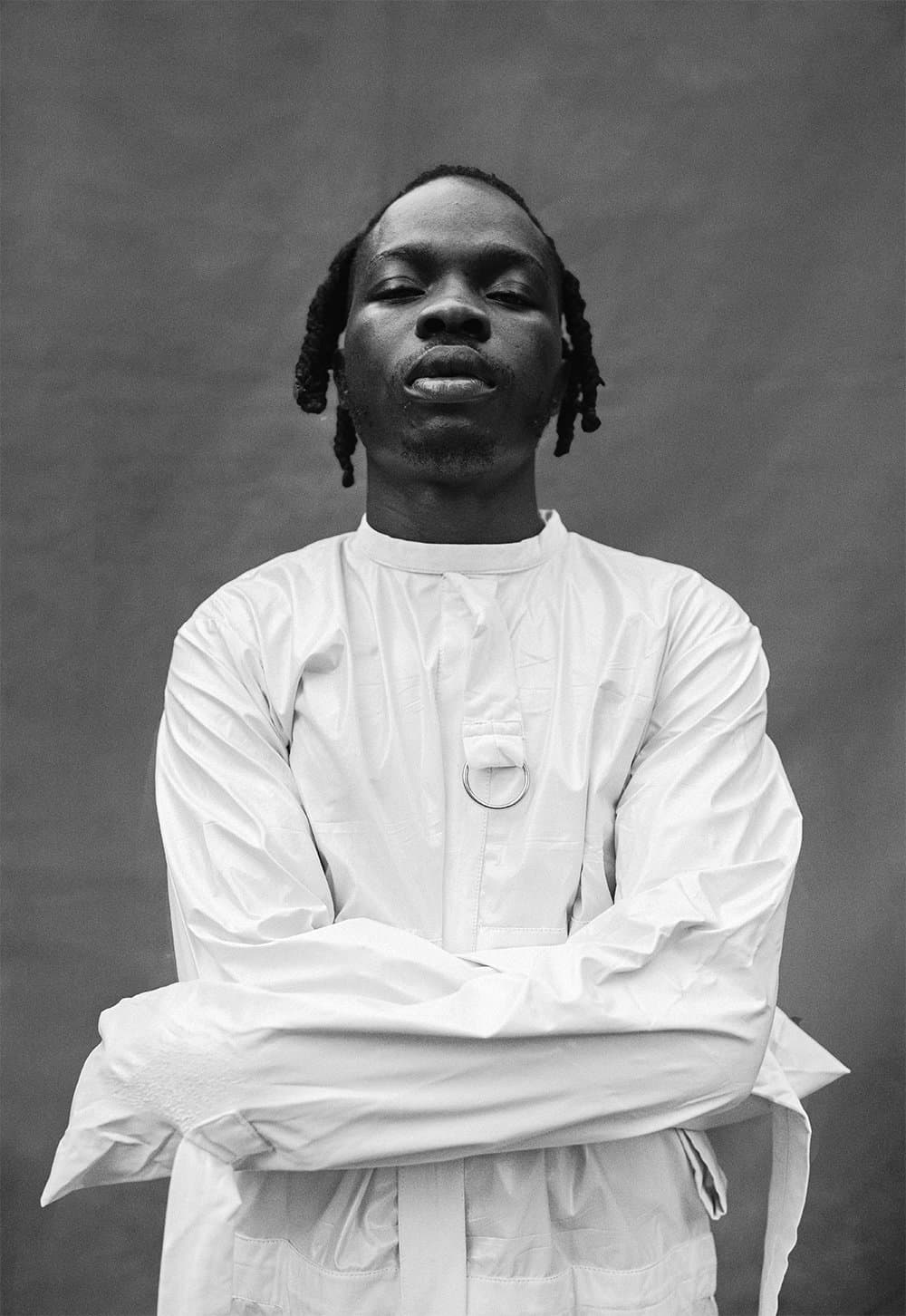

“We need to change how it is [here]. They don’t respect women, I respect women. They don’t treat the poor nice, I treat everyone nice.”

Re-adjusting his protective mask that slipped momentarily, Naira expertly pinpoints the je ne sais quois factor that has made him not just a global superstar, but one of the most talked about people in the country. “I’m not saying I’m the best artist in Nigeria,” he says in an exaggeratedly innocent tone, before getting more serious. “But it’s not just about the music, you know, it’s everything. It’s me, the personality, the foundation. Actually, it’s not just me. It’s me and my Marlians.”

Naira Marley has nothing left to prove. He went on a run many artists can only dream of, picking (and winning) fights all along the way. The days spent honing his craft, travelling through uncountable musical spheres, picking up little details along the way, it’s all paid off. He doesn’t see himself stop anytime soon, though. “People say ‘Opotoyi’ is my biggest song, other people say ‘Am I A Yahoo Boy’, others say ‘Soapy’. I’m trying to beat my own record, and drop my biggest song. It doesn’t stop, I’m always trying to get better.”