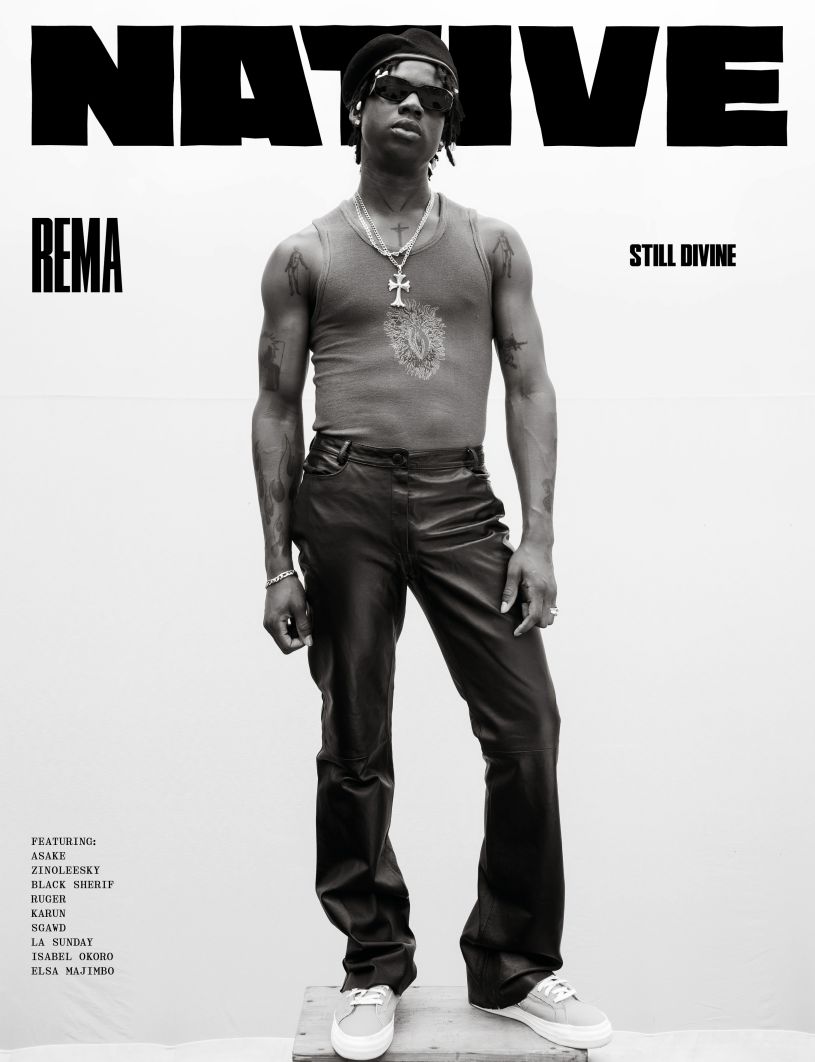

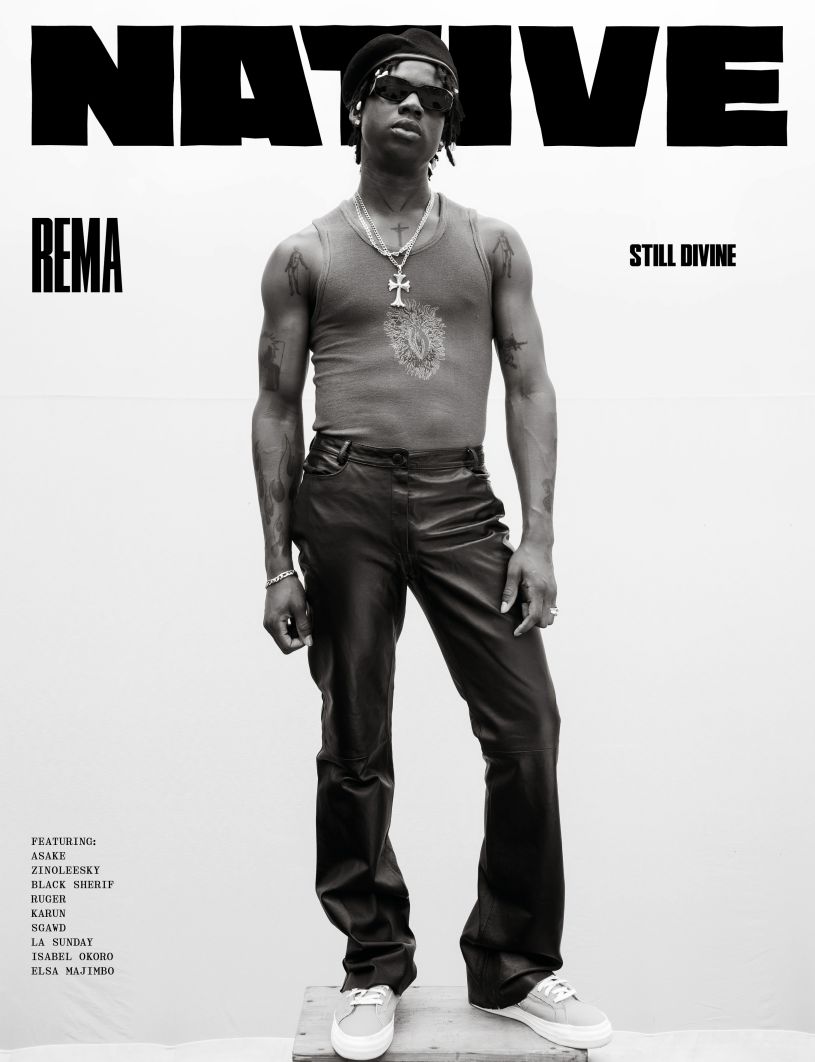

STILL DIVINE

Rema

Words by Seni Saraki

Credits:

Special Thanks: Sean, Damo

Rema Wears Converse

Words by Seni Saraki

PARIS, France – We’re sat in a studio deep in the 8th arrondissement, in Paris. Rema is here for the Dior show, flown out and lodged by Kim Jones, the LVHM brand’s creative director. Pictures would surface the next day of a Dior’d out Rema, standing next to Wizkid, Naomi Campbell and his label mate, the pink-haired and eye-patch adorning Ruger.

Rema is racing through flows on a beat he’s found deep in his inbox. After laying down a sure-to-be anthemic hook, in which he’s incessantly repeating the phrase “can’t stop,” with a cadence that would sound right at home on Lil Uzi Vert’s Eternal Atake, he shimmies through a punchline-packed verse. He starts off comparing himself to Tony Stark, then laments about his trust issues since finding fame and how his heart has been frozen, before landing on the verse-closer, which is sure to ruffle more than a few feathers: “In this generation I’m like Hov!” he declares triumphantly.

There’s that moment in a studio session where everyone present realises something special is happening. That line triggered that reaction. Dera, Rema’s trusted right-hand on most of his travails, takes a quick look up from scrolling through his IG feed, and chuckles lightly. The studio engineer turns back to the rest of the room without saying a word, but his look alone screamed “did you guys hear that?” The French security guard, who hadn’t moved an inch or uttered a word since my arrival, did his best Thierry Henry impression, with an almost comically stereotypical puff-out-of-the-cheeks, which to me, translated to a good old-fashioned British “bloody hell!”

As for Divine himself, as he’s known to an increasingly smaller proportion of people in his life, he barely flinches. He’s ready to do his ad-libs to finish up the song. It’s already 5PM, and he’s been keeping a close eye on the time, as he needs to race across town to get ready for two performances he has on the night: headlining a fashion week party for Converse, before heading to a private event at Soho House. As we board the Mercedes Super Sprinter taking us back to the centre of the city, Rema asks the driver to connect his phone to the sound system. For the next thirty minutes, he shuffles between playing me some unreleased songs, the latest Nigerian rappers he’s into – like Psycho YP and Khaid – the latest Lil Durk album, all before landing on the song he’s just recorded in the studio, on repeat for the final portion of the journey. He graciously drops me off first – with a promise to “link later” – while he darts to his hotel to get changed for his first show of the night.

As I sit down for dinner at Diep (a personal Paris tradition) that line, ”In this generation I’m like Hov!” reverberates in my head, as if on a constant loop.

It’s a bold claim, to anoint yourself the Jay-Z of your generation, but you can see why he would think so.

In three short years, the boy that was rapping out of the car window, has become the young man on top of the world. Rema has scaled to the pinnacle of the music pyramid, and he’s done so seemingly without even breaking a sweat. Signing jointly to Jonzing World and the machine that is Mavin Records in 2019, he was a young but confident boy, tipped as The Next Big Thing. Not only has he lived up to the billing, but it’s fair to say he may have already surpassed the expectations the ever-sceptical Nigerian music industry had for him. Today, he sits atop the Billboard US Afrobeats Charts for a record 11th week, as a result of his borderline fanfic collaboration with Selena Gomez. Who would have thought The Boy from Benin City would go multi-platinum with Alex Russo from Waverly Place? Not him, that’s for sure.

“I’ve been a fan of Selena for the longest,” he says rather honestly, when I ask him how the collaboration for the remix of his hit single “Calm Down” came about. “And to my surprise, she’s been rocking with me too since the first EP! We got connected and we’ve been communicating for a while, so I [just] asked her to be on the record and she blessed me with a beautiful verse.”

Predicting which prodigies will live up to their grandiose has increasingly become a sport in itself. From music to sports to tech and everything in between, the hype machine that churns on Obasanjo’s internet has never been more potent. Any young footballer with a few goals and a diminutive stature is roundly dubbed “The Lionel Messi of [insert country here].” Once a tech company hits a couple of sales records with an enigmatic CEO, they’re quickly named “The Next Apple.” And any Nigerian artist with a hit song, that sings in any note above baritone, is hurriedly christened “The New Wizkid.” In some ways, it’s just human nature. To consider something new, we sometimes find comfort in comparing said new thing to something of the past. It makes it less scary and easier to digest. And truth be told, especially in the music industry, it’s impossible not to be inspired by those that came before you. How can we expect any Nigerian artist born after 1992 to *not* have elements of Ojuelegba’s Greatest Export in their cadence? Would they really be students of the game if they didn’t attempt to adopt aspects of the flow and versatility of The African Giant? Would they not be shortchanging themselves, to ignore the benefits of creative collaboration exemplified over the last decade by 30BG’s Head Honcho? If anything, it’s been refreshing to see this new generation of young superstars, led by Rema, openly embracing their influences and exploring novel ways to build upon the foundations laid before them.

But few have had to do this under the pressure that comes with the unforgiving gaze of the Nigerian public from day one. The man himself says “there’s pressure for every person who vows to take the game to the next level, I won’t deny feeling pressure once in a while…but I don’t let it bother my peace for [too] long.”

While today in 2022, Mavin Records are renowned as a Pop music machine, West Africa’s answer to South Korea’s Big Hit Music (home to BTS), it’s easy to forget that in the first quarter of 2019, this wasn’t quite the case. By this point, Don Jazzy’s name had already been long since etched in the history books of Nigerian music as one of the true greats, but he was embarking on a fresh new journey as a label head. Following Mavin 2.0, the all-things-considered comparatively underwhelming iteration of the legendary post-Mo’Hits label, Jazzy knew something needed to change. So, while there was never a formal announcement of a third act in the house he built following his infamous musical divorce from the once revered D’Banj, the signing of Rema all but confirmed that Jazzy’s iconic walking stick was pointing in a new direction.

Rema was something fresh, something different. I still remember hearing “Dumebi”, his scene-stopping debut single, for the first time, and looking around in sheer disbelief, completely blown away by what I was listening to. Firstly, the absolute audacity to open up your debut single with the phrase “another banger!” – one that we would quickly become a familiar battlecry to mark Rema’s presence on tracks – is legendary in itself. But to then back that up, the way he did, is the stuff legends are made of. Listening back today, what strikes me most isn’t the runaway-hit nature of the hook, or the tongue-in-cheek lyrics that have gone on to define Rema’s writing style, but it’s his most dangerous and least talked about weapon: his voice. A vocal cocktail that, on first listen, sounded somewhere in-between Wizkid and Cruel Santino fka Santi, with a bit of Owl Pharaoh era Travis Scott sprinkled in there, the manner in which a young Divine was effortlessly contorting and manipulating his voice around flows and in and out of pockets, is something that, till this day, sounds alien. An amalgamation of numerous soundscapes, but somehow still sounding like himself – despite the longing to draw comparisons with the familiar voices that came before and undoubtedly inspired him – “Dumebi” was nothing like you’d ever heard before.

“They [Mavin Records] accept my sound for what it is; [as] crazy as it sounds,” Divine told this very publication back in April 2019, in what was his first ever interview. “The Trap and the Rock and everything. Most people would try to change your sound but they believe in mine. I’m not scared of dropping any type of song cause I’m very confident, I’m ready, I’m talented. Every time I get in the studio, I create something crazy.”

Looking at Rema’s ascent today through the lens of this statement from a young(er) Divine, is both at once fascinating and illuminating, as a question of sound would follow him almost at every lofty milestone.

Rema’s time at Mavin, sonically, has always seemed, from the outside, to be somewhat of a balancing act. That is, balancing his seemingly endless potential for superstardom with the pressure that comes with being the face of a new dynasty. While in 2019, immediately following the release of his wildly-successful debut EP, he stated he had the full backing of the label’s big wigs to explore his sound as he saw fit, there has been an unquestionable downtick in the Trap version of Rema that many Ravers – as he affectionately calls his fanbase – were initially drawn to. Songs like “American Love” and “Boulevard” off his Freestyle EP, are nowhere to be found on his unprecedentedly successful debut album Rave & Roses, which released earlier this year, and as of writing has amassed one billion streams globally. When asked about this, Rema responds very much in character: “…it’s a strategised journey, and I’ve done a good job to make you guys think it all ends there. Let’s see what the future holds…”

Today, Rema labels his sound as Afro-Rave: a self-defined genre he says is a sub-genre of Afrobeats. “It includes the melody, delivery and diversity and its flexibility to maintain its own stance, sound-wise, in any beats pattern and outside Afro,” he told Rolling Stone earlier this year. While plenty of artists operate under self-defined genres – or even refuse to operate under any genre at all – what’s particularly interesting with Rema, is just how he has arrived at this genre name and sound.

In Easter of 2019, a ski-masked Rema exploded onto the Homecoming main stage, the festival started by Grace Ladoja to further encourage cultural exchange between Nigeria and the UK. In his debut live performance, it was clear to see he was here to stay. Not quite the polished, near-peerless act that we see today touring the world, the high octane energy and unmistakable star power was already evident in the new heir to the Mavin dynasty.

The last two decades has seen a gradual democratisation of music, more recently expedited by the invention and rapid adoption by record labels, artists and fans to digital service providers such as Spotify, Apple Music, Audiomack et al. It has never been easier for anyone to record a song, and have it available to hundreds of millions of people, in just a matter of hours. Whilst the pros and cons of this liberation have been argued across record label boardrooms and Twitter spaces alike, a truly gargantuan spanner was thrown into the already cluttered works in the early months of 2020. No matter how many recipes you learnt, how fit you got, or how much you made off crypto investments, it would be thoughtless for anyone to suggest the peak of the Coronavirus pandemic was anything but a tragedy. On top of the effects it had on the most vulnerable in society, the pandemic ravaged many industries, with the music business being right at the front of this pack. Pollstar, a music business trade publication, estimated that at the end of 2020, the live events industry had lost over $30 billion. For many artists, especially from Africa, live show revenue accounts for the lion’s share of their income. With this being wiped out, out of necessity, many artists started paying greater attention to their digital outlets, such as the aforementioned DSPs, and social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Youtube and Triller. This industry-wide shift to be purely digital aided some artists, who may have been more adept to recording and releasing music, staying online, and interacting with fans from the confines of their homes.

But for artists like Rema, this wasn’t what he signed up for.

“I signed out, but popped up on another floor above the venue and started performing again on a risky platform,” Divine excitedly tells me, when asked about his best experience on his Rave & Roses tour. “The fans had to hold me to stop me from falling. They probably thought I was on drugs,” he says, laughing, “but I don’t do none of that. Seeing them rave after thinking the show was done was wild.”

Yes, he is a recording artist, but more than anything, Rema is a performing artist. He appears most comfortable on a stage, sharing special moments with his adoring Ravers. And crucially, that seems to have been a pivotal influence into how he found his own sound, amongst the diverse skillset he so clearly possesses.

“It hit me,” he says of his invention of Afro-Rave. “I worked consistently… different ideas, [the] same feeling, [the] same tingle. In the process of making a song, I already know what the performance is gonna be like, it adds to the excitement while I’m going off in front of the mic.”

While his OG “Spiderman”-Rema fans may have felt his debut album was missing crucial elements of The Boy from Benin City they initially fell in love with, when you see him perform it live, it becomes increasingly difficult to agree with this summation. Watching him run through the raucous, critic-answering “Are You There” looks like something out of a 2012 Odd Future show. Even sultry numbers like the summer heater “Soundgasm” induced moshpits across North America and Europe over the summer.

For what it’s worth, Rema had no doubts, as he bullishly tells me, “When I first labelled my sound Afro-Rave, I said my album would seal the claim for good, and that’s what I went ahead to do.” On first listen in the confines of your home, this statement may seem misguided, but that is exactly what he has done. To experience Rema live in performance, is to see his Afro-Rave in full power: this sonic fusion of his Rap/rave culture influences, paired with the tried and tested Afropop-centred tutelage of Don Jazzy and his Mavin machine, all underpinned by an incomparable voice, makes for a perfectly – albeit, delicately – balanced pendulum.

“Everything that you hear is from my soul. I rarely have an external principle lead my spirit to create. I’m not boxed in. I can be on [any] genre and still sound like me. Afro-Rave is ME,” he declares triumphantly. His versatility and, as he calls it, “flexibility” in his sound was clear to see this year more than any, and especially so for this writer. Working with Rema on the Black Panther: Wakanda Forever Soundtrack was an experience like few others. First, he came in to record a fiery, urgent battlecry over a seemingly Mike Dean inspired sound bed, produced by London, his go-to beat-smith, which ended up being used as the soundtrack for the final trailer for the Marvel blockbuster. Months later, in the proverbial Fergie time of the recording process, he delivered two quick fire verses at the request of the film’s composer Ludwig Goransson, in under 24 hours: one, “Wake Up” a bouncy collaboration with artist and (co-)producer Bloody Civilian – one of the most exciting artists out of Nigeria this year – and another, “Pantera”, a cross-culture bar session with Mexican rapper Aleman, also produced by Goransson. Watching Rema turn these songs around, in the middle of the biggest tour of his life, as his Selena Gomez-assisted pure Afropop smash “Calm Down” ruled the charts, was something to marvel at. Being nimble enough to showcase a completely different side to the sonic palette we had been served all year, paired with a superhuman work ethic that is practically unrivalled in his generation where he’s from, is exactly why he’s such a unicorn in world music today.

For any artist from Nigeria, striking a balance between creativity and profitability once you have “blown” – the infamous term ascribed to artists who the public and the music industry perceive to have crossed over to mainstream consciousness – is one of the most difficult things to do. For Rema, it’s even harder than for most. Coming out of the gate as not just a new Mavin artist, but the de-facto Crown Prince of Don Jazzy’s new empire, the spotlight has been bright from day one.

The week before we see each other in Paris, we’re all in Malta for a music festival whose lineup is dominated by Nigerian artists such as Wizkid, BOJ, BNXN fka Buju, Lojay and Rema himself. Seeing this array of artists, all at different points in their careers, performing at a festival on a European island, was one of the many pinch-me Afropop moments of the year. But more than that, watching them interact with each other is even more heartwarming. They all watched each other’s sets from the crowd, singing along to the plethora of hits across their catalogues, before convening on a joint table to dance the night away at the after-party.

Fuelled by the increasingly rabid stan culture that has risen almost in tandem with the popularity of the genre, it is a phenomenally rare sight for artists across generations to embrace each other in such a genuine way. The various fan groups have seemingly made a living pitting the best artists the country has to offer against each other, taking pages out of the Pop standom books of their US counterparts. Despite moments like DLT Malta showing that there is still a level of camaraderie and legitimate love and respect for one another, it has sadly led to many of Rema’s one-time idols and his age contemporaries becoming rivals in record time.

“As time goes by, I’ve grown to understand that comparisons will happen regardless, even when I try to stop the fans,” he says pensively. “But at least they know I don’t support it…” he sighs, almost resigned to the fact that this is simply where the industry finds itself. “But in this game…competition is inevitable,” he continues, after some thought, “and I’m enjoying it as long as it’s healthy. I know how much work I put in to stand out, the criticisms and the battles I faced to show people the light.”

Rema has always been confident, and rarely shies away from speaking his mind, but one can’t help but feel that, this year, he is embracing his role as not just the leading artist on the most successful record label since the turn of the century, but as a leader of a new generation of artists who are not afraid to welcome healthy competition, whether it’s coming from one of their OGs, or a peer.

“Telling me I can’t/That’s an insult/Drop my shit when the OG drops!”, he barbs on the Paris freestyle, shortly before proclaiming himself to be the Jay-Z of his generation. When I ask him what the first line is about, he just smiles, almost as if to say “whomever the shoe fits.”

It’s the summer of 2021, and Rema has ditched his crew for the day, and wanders the streets of Brick Lane in his Chucks, without a care in the world. He’s in London to play a string of festivals, his first since the pandemic hit, and you can see the excitement in his eyes. He can’t wait to get back out there. We pop into a corner shop, and he takes a picture with a Monster Energy Drink can, one of the latest brands who are paying very handsomely to be associated with The Rave Lord. He says he’ll post it on his Instagram later on. Afterwards, he pays a studio visit to Slawn, the Nigerian artist and skater who has turned the art world upside down. Rema wants Slawn to join him on stage at an upcoming performance at Wireless Festival, holding a piece of his art – which till that point, you could only acquire by paying tens of thousands of dollars, as collectors such as Lil Uzi Very and Davido did… or by emerging victorious in a fight club (yes, a real fight club).

Rema explains to me later on that he’s always been into art, and the cartoons we’ve seen on his single and EP covers have all been conceptualised by himself. He says one day, he hopes to have an art exhibition of his own, but he understands that “the art world is different,” implying he’ll need to gradually ease himself into it.

The more time I spend with Rema, the clearer it becomes that despite the joint efforts of Mavin and Jonzing World to support his career, so much of what you see has been schemed up by the man himself. Behind the fireball of energy we see on stages across the world, is a creative and marketing mastermind, pulling the strings of his own every move. While he does act on impulse and sheer belief sometimes in his own gut feeling, there is always a high degree of calculation. Nothing he does is by chance.

Upon leaving Slawn’s studio, Rema says he wants to stop and get a drink at the type of standard, local outdoor bar that litters the roads of East London. He’s spent more time in the capital, and knows not to take good weather for granted, so we sit outside taking it in.

“This shit is so crazy, man,” Divine says, slightly choked up. I look up from my phone, thinking he’s about to show me something on Instagram or Twitter, but he’s staring upwards, just marvelling at the London skies. I ask him if he’s ok.

“I’m great, bro. This shit is just crazy.”

He explains to me that just before the untimely death of his father in the late 2010s, his family had made plans to come to London. Visas were already being processed, and he had even picked out the car he wanted to drive once he got here. Since then, Divine also tragically lost his older brother, someone he regularly credits with introducing him to many of the sounds that influenced him as an aspiring artist. Behind the jovial Rave Lord is still Divine, the young boy from Benin who has overcome so much just to get here, and at the end of the day, is simply trying to make his family proud.

And that he has done. A year and some change on from that moment, and Rema has changed the life of his mother, and everyone around him. From the 19-year-old upstart who arrived at his first ever photo-shoot and interview with just his manager Sean, to the young mogul-in-the-making of today, who has crafted a best-in-class creative team around him of producers, stylists, photographers and directors – Rema is doing everything he said he would. He’s worked with brands such as Converse, Pepsi, Monster and BooHoo. He appeared on the soundtrack for one of the biggest movie franchises of our time. His world tour this year has been one of the hottest tickets in town, across any genre, climaxing with back-to-back sold out nights at the O2 Academy Brixton with a slew of A-list surprise guests. Artists from Madonna to Steve Lacy have pulled up to his shows, just as fans. Commercially, he has the most successful debut album by an artist from Nigeria, ever, with “Calm Down” becoming one of the biggest Afropop songs of all time, racking up 400 million streams globally till date. But how does it feel, for the boy that has it all? Is he happy?

“I feel nothing but blessed and honoured,” he says, clearly reflecting on his young but successful career as Rema. “I have peace, I have good wealth, I can control my every move, perception and narrative. I have love and I have wealth – what more does a man really need?” he proclaims, firmly back in character. While he does lament the things Divine can’t do anymore, now that he’s Rema, such as “take a walk, ride a bike or skateboard or even go to the mall,” he is self-aware enough to know that this is part of the package he signed up for. This is what he fought for, all those long days and nights refining his sound, fighting for his own voice.

With rumours of a deluxe album to come, and whispers of the start of an almighty battle for his signature whenever his current deal expires, Rema is as calm as ever. He may not say much, but he hears and sees everything.

As someone who values loyalty above all else, he will not let himself get distracted by anything other than the job at hand. On the outro to the Paris freestyle, he sings in a soft voice, “Too many people depend on me, I can’t stop/ I do this for my family, I can’t stop/ If you can hear me don’t stop…if you can hear me don’t stop…if you can hear me don’t stop…if you can hear me, don’t stop.” Sounding more like Divine than Rema in that brief moment, one could surmise he’s singing to the next young kid from his city who’s trying to make it out. But at the same time, you can’t help but feel he’s singing to himself.

“[Fame] is an opportunity to share your art and speak your truth, while the world’s attention is on you,” he elegantly proffers, as a response to what the concept of fame means to him, today.

Well, right now, all eyes are Still on Divine. And Rema is not stopping anytime soon.